Now Playing

Current DJ: Liz Mason

Smoking Popes Allegiance (featuring Scott Lucas) from single (self-released) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is a recap of the year 2017 at the movies.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Clarence:

The calendar on the wall says 2017 is all done. Let's honor the film critics code and reflect on the year that was, shall we?

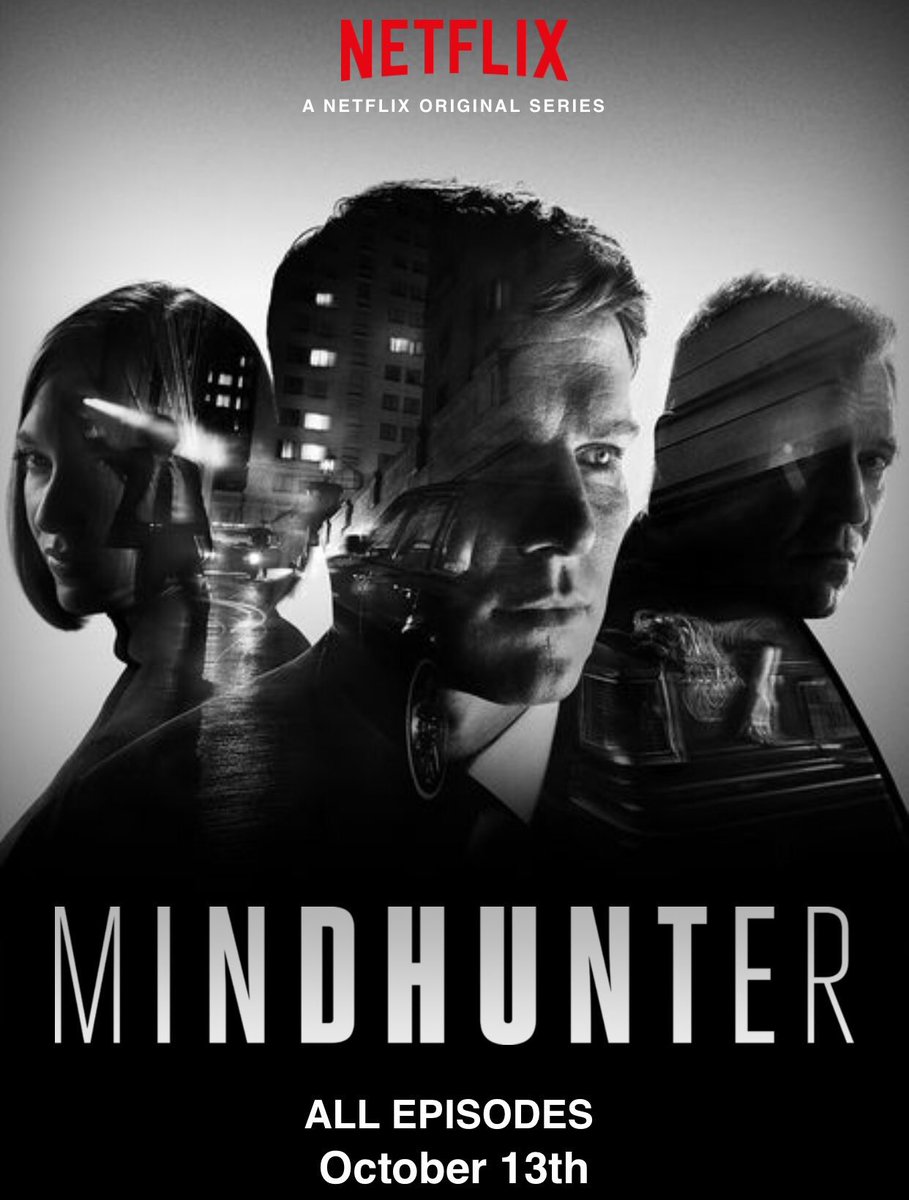

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the Netflix series Mindhunter.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

Kevin:

While delving into the first few episodes of Netflix's Mindhunter, I couldn't help but think about how much more I'd enjoy the crime series if Bunk and McNulty from The Wire were working these murder cases instead of FBI agents Holden Ford (Jonathan Groff) and Bill Tench (Holt McCallany). Or gimme Columbo, rumpled trenchcoat and all? As it turns out, Mindhunter prompted a trip down memory lane with regards to the genre... usually via comparisons not to its benefit.

It's clear that -- at least to Hollywood -- FBI folks are wound just a bit tighter than your typical big-city homicide detectives. And much more humorless. I loved The Silence of the Lambs, but Jodie Foster's Clarice Starling was a no-nonsense investigator who wasn't exactly dripping with personality. And neither are Ford and Tench, who slip into time-worn tropes early on: Ford as the wide-eyed, young idealist, and Tench as the world-weary veteran.

The two are partners in the late 1970s, traveling the country and teaching crimefighting techniques to local law-enforcement agencies. Early on, Ford develops a fascination with what's deemed as a new, sinister brand of criminal: the serial killer, whose motives aren't related to revenge or personal gain. Soon, Dr. Wendy Carr (Anna Torv), a psychology professor, joins the duo, and the game is afoot.

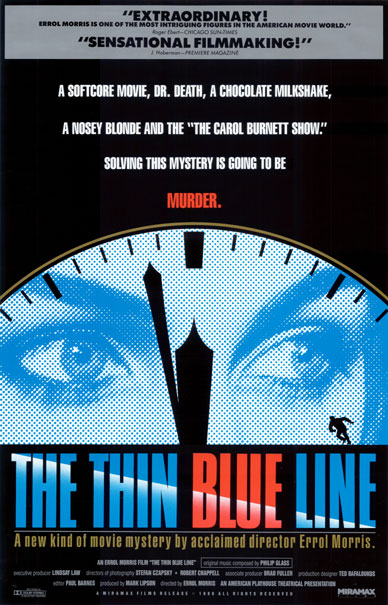

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the classic 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Clarence:

When I was an undergraduate, I took a class I think was called “Visualization and Reality,” or something like that. We studied a bunch of different topics like depth perception in painting, movie effects, holograms, etc. It was a fun, eye-opening experience, but for the longest time I didn’t think the class was worth anything other than helping me get credit toward my major.

Now, though, I feel that was one of those classes where I learned something that I carry with me to this day – that “reality,” or “truth,” may not be absolute, because it depends on perceptions, and perceptions differ depending on who is doing the perceiving.

This is the idea behind Errol Morris’ 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line. The movie explores the answer to the question of who shot and killed police officer Robert Wood late at night in November 1976.

Two men, David Ray Harris and Randall Adams, were at the scene of the crime. But the answer to the question of who fired the gun differs depending on who supposedly saw the event as well as who was involved in the subsequent proceedings.

Along the way, the audience listens to the viewpoints, of witnesses, prosecutors, and police officers involved in the case. Everyone has their own motivations for what they believe in and the actions they take. “Getting to the truth about what happened” isn’t at the top of all, or even most, of these individuals’ lists.

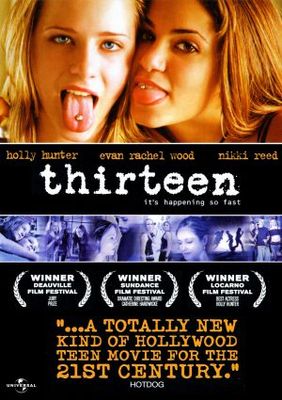

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 2003 film Thirteen.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

Kevin:

Clarence, we were just talking about the challenge of writing for young folks during our discussion of The Florida Project, Penning lines for the teenage set seen in Thirteen might actually be tougher than constructing dialogue for first-graders? It's relatively easy for an adult to serve as a fly on the wall around tykes, but older kids are a far more guarded group.

Cameron Crowe famously went undercover at a California high school in order to mine the material for his landmark book (and later film), Fast Times at Ridgemont High, but here director Catherine Hardwicke goes one better; her co-screenwriter is actress Nikki Reed (age 14 during filming), who mined her own life for this quasi-autobiographical tale.

And what a life that is -- The Wonder Years, this ain't. Reed's Alpha Female, Evie, serves as the gateway for Tracy Freeland (Evan Rachel Wood), who decides to leave behind her nerdy circle of friends and make a concerted effort to move rapidly up her school's social ladder... though this comes with a hefty price. Before long, the two are ditching school, huffing, slugging each other (and self-harming when they're not), and engaging in sexual behavior far more mature than one would wish for a middle-schooler.

All the while, Tracy's relationship with her mom Melanie (Holly Hunter, in an Academy Award-nominated performance) steadily erodes. Melanie, a divorced, harried hairdresser, is bewildered by the hostile stranger that her daughter's become. As a recovering alcoholic who receives scant support from her ex-husband, Melanie is ill-equipped to keep on top of Tracy's life and reign in her wild behavior.

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the recent news reports of sexual assault and harassment in the arts and entertainment worlds.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Kevin, I’m sure you’ve heard about what’s going on with Hollywood mogul and serial rapist Harvey Weinstein. I've been following this story along with the string of others after it and thinking about what it means for the film industry.

While I never followed the details of the personal lives of Harvey or his brother Bob, for the last few decades I have been a huge fan of the company they founded, Miramax (producer and/or distributor of a string of '90s landmarks like Pulp Fiction, Good Will Hunting, The Crying Game, and Clerks).

To me, this was a company that proved quality and profitability are not mutually exclusive in mass-market filmmaking. Even after the Weinsteins sold Miramax to Disney in 1993, they represented the idea that an independent operation could not only compete but be successful in movies, an idea that was inspirational to me and many others.

With the architect of this media miracle now hiding overseas, it’s impossible to ignore the fact that the “casting couch” mentality that so many people (myself included) dismissed as just a fact of life of Tinsel Town is, literally and definitively, rape culture.