Now Playing

Current DJ: Michael B.

The Replacements I Will Dare from Let It Be (Twin/Tone) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

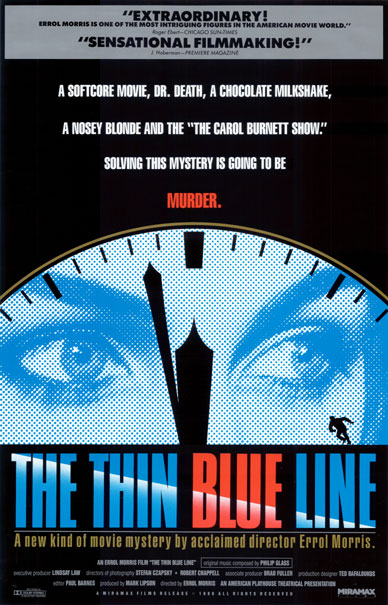

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the classic 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Clarence:

When I was an undergraduate, I took a class I think was called “Visualization and Reality,” or something like that. We studied a bunch of different topics like depth perception in painting, movie effects, holograms, etc. It was a fun, eye-opening experience, but for the longest time I didn’t think the class was worth anything other than helping me get credit toward my major.

Now, though, I feel that was one of those classes where I learned something that I carry with me to this day – that “reality,” or “truth,” may not be absolute, because it depends on perceptions, and perceptions differ depending on who is doing the perceiving.

This is the idea behind Errol Morris’ 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line. The movie explores the answer to the question of who shot and killed police officer Robert Wood late at night in November 1976.

Two men, David Ray Harris and Randall Adams, were at the scene of the crime. But the answer to the question of who fired the gun differs depending on who supposedly saw the event as well as who was involved in the subsequent proceedings.

Along the way, the audience listens to the viewpoints, of witnesses, prosecutors, and police officers involved in the case. Everyone has their own motivations for what they believe in and the actions they take. “Getting to the truth about what happened” isn’t at the top of all, or even most, of these individuals’ lists.

In the almost 30 years since this film was released, two cultural developments have occurred that I think reflect the impact this movie had. Crime investigation shows featuring recreations of gruesome murders as well as subsequent investigations of them have become staples of cable TV.

At the same time, ventures like The Innocence Project have established themselves as resources to help people who feel they have been wrongfully convicted something that happens a LOT in the United States.

Kevin, have you seen this movie before? If so, has your opinion about it changed at all since the last time you saw it?

Kevin:

I have seen TTBL before, and while it is a classic, it was also a bit jarring to see how far crime documentaries have progressed in terms of technical quality? Two elements jumped out in particular:

1) The lack of any name/title placards. I don't think there was one in the entire film? As such, it was sometimes a bit confusing to figure out who was talking as the faces started bouncing back and forth (especially when the cops/lawyers got involved in the act). Of course, such frills were much more time-consuming to produce in the days before digital editing.

2) The re-enactments. I don't watch a tremendous amount of true-crime television, and I know that some television shows still employ them, but... they kinda look a bit hokey to me? Interestingly, this was one of the original selling points of the film, as the folks at Mirimax (particularly, yes, Harvey Weinstein -- too soon?) wanted to avoid the label of "documentary" at all costs. Until the days of Hoop Dreams and Michael Moore, the only successful documentaries in movie theaters were almost exclusively concert films.

Small bones to pick with such an important film, however -- the movie was likely the principle catalyst for the exoneration of Randall Adams, who was released from prison roughly one year after TTBL was released.

You mentioned "truth." It occurred to me years ago that one of the problems with the criminal justice system is that a prosecutor's job isn't to focus on obtaining the truth, as they're evaluated (and re-elected) based on their prosecution records. As far as they're concerned, the "truth" has already been established. Of course, criminal defense teams are judged similarly -- who would hire an attorney who's more concerned with digging into nebulous facts than presenting a rebuttal? In HBO's The Night Of (a terrific procedural), there's a great exchange between defense attorney John Stone and his client, Nasir Khan, which spells out the game:

-----

Stone: They come up with their story. We come up with ours. The jury gets to decide which they like best. Now, the good news is we get to hear what their story is first before we have to tell them ours. So we keep our mouths shut until we know what they're doing.

Khan: You keep saying "story" like I'm making it up. I want to tell you the truth.

Stone: You really, really don't. I don't want to be stuck with the truth. Not until I have to be.

-----

One level down from the DA's office are the cops who are under pressure to identify a guilty party. And for a murder of a police officer, that pressure is ramped up a hundredfold. There were scant leads in this case, and it took a month of exhaustive investigative work to track down Harris and Adams. At point does finding "a" suspect become more important than finding the "right" suspect? But what was bizarre was that the police had both suspects in the exact same location; they simply accused the wrong one, despite much evidence to the contrary. Was it simply that the DA thought the jury would be much more likely to convict a 28-year-old than a teenager?

Besides The Night Of, there's another fantastic documentary that comes to mind: Murder on a Sunday Morning, where a 15-year-old black kid is out walking his dog one morning in Florida... and all of a sudden, he's arrested -- and later convicted -- of murder. Hey, the prosecution had a signed confession! All it took to get one was an afternoon in the woods with a bunch of police (both white and black). The suspect didn't even have to write it himself, as the helpful detectives took care of that for him. If not for some crusading public defense attorneys, he might still be in jail.

Also, I'm in the midst of reading The Man From The Train by Bill James, about a serial-killer case from a century ago. If we think crime investigations are rife with errors today, well, our local police department might as well be Scotland Yard compared to what was available 100 years ago. Most competent investigators had to be hired (such as the Pinkertons), and the number of wrong place/wrong time arrests were enormous.

That said, the natural inclination of leaning towards the assumption of guilt is still a tough mindset to overcome. What do you think of the idea of professional juries, people who are presumably better-educated than your average folk, and might be more able to sift through conflicting arguments? One of the minor shortcomings of TTBL is that they never presented much info on why the Dallas jury convicted Adams. Of course, the film was picking up the trail of the story over a decade later.

Also, do you have any other favorite crime shows/documentaries? And have you ever served on a jury yourself?

Clarence:

I served on a jury once in my life. It was in Boston, and it was a civil suit a young woman brought against her former employer whom she claimed fired her because she was a woman. Her former boss countered that it was because she was bad at her job. I don’t remember any of the details. All I remember is It didn’t take us long to find for the defendant (the boss). It wasn’t controversial, the plaintiff just didn’t have a case.

The idea of professional jurors is interesting. So many people do everything they can to avoid jury duty, why not make it a full-time job? You can treat them like notary publics, in that they must maintain a license and good standing in the community.

Or, we could also change the nature of our court system. Instead of a contest between two opposing parties, make trials a form of fact-finding mission whose goal is to discover what actually happened instead of who can make the most convincing argument. From my extremely limited understanding of the subject, this is how it’s done in some European countries now.

The problem with the “truth” is in its severe subjectivity. Two people can look at the same act and come to completely different conclusions about why it happened and what should be done about it. In Adam’s case, his class status led the police, the lawyers, and the jurors to treat him with a certain dismissiveness, because who gives a sh*t about some drifter who was probably up to no good anyway? As long as somebody pays for the harm done to society’s representatives (in this case, the cop), that’s what matters. [You can trace that theme through this country’s history from lynch mobs to the invasion of Iraq.]

That conversation you cited would be a nightmare for me. Imagine your life depending on who puts on the better show for a bunch of people who don’t want to be there judging you? It seems like it would take a monumental shift in public opinion (not to mention changes in laws) to do it differently. If you were in that situation, would you rather the case be decided by a jury of your peers (some of whom may not have enough knowledge or interest in your case to make an informed decision) or a single judge who knows the law but may have their own biases?

I agree with you about how the lack of title cards in the movie makes it hard to keep track of who’s doing what. But I thought the re-enactments were pretty good, especially comparing them to what’s seen on a typical cable crime show. Those artful sequences, combined with the flat, static cinematography and the music by Philip Glass, drains the sensationalism from the story and helps the viewer focus in on the existential essence of the story.

I’m not a huge fan of crime-based entertainment, at least not dealing with murder. The most popular crime shows (Law & Order, etc.) just seem too morbid to me. If I want to dwell on horrible murders and senseless violence, I’ll watch the news.

One particular crime fiction I do like, though, is theft. Most of my favorite crime movies of all time (Rififi, The Killing, The Usual Suspects, Reservoir Dogs, Sexy Beast...I could name several others) involve somebody trying to steal something. I wonder if the kind of crime fiction someone likes might say something about them? Do you have any interest in that sub-genre?

Kevin:

I am a fan of heist films -- The Score (2001, with Brando/De Niro/Norton) comes to mind, and on a related note -- do things ever go right for folks who are contemplating "one last job?" This trope might be right up there with the grizzled police veteran who starts talking about how they're days away from retirement.

I'm guessing we're of like minds regarding the type of heist tale we appreciate as well. Reservoir Dogs, a bank-robbery tale where the "action" is related to the audience in hindsight, is a low-fi tale. No thunderous music during the getaway*. No slow-motion John Woo-style action shots. Gritty.

[*Did it seem strange to you that folks would knock off a bank while wearing suits and dress shoes? Especially as a fair amount of sprinting was involved? Wouldn't you rather opt for track pants and sneakers? And how come there was no getaway car at the ready, a la Baby Driver?]

The concept of "fact-finding missions" sounds intriguing -- I'd want to know more about exactly how Europe is handling this. On its face, it seems problematic from a logistical standpoint. Whose jurisdiction do the police investigators fall under? Is there still a traditional defense team? What I'm also curious about is whether there are particular problems in the American court system that are absent in other countries. Or perhaps there will always be inequities that are impossible to eliminate?

As far as preferring my fate to be decided by a jury of peers vs a single judge... that's a great question. Of course, it depends on where I'm living! There's also the nagging sense that perhaps better-qualified jurors are also more crafty at evading the jury-selection process. Have there been studies done on the educational backgrounds of selected jurors relative to their communities? (Not that a degree is a be-all, end-all, but it's a useful shorthand.) I'd also be interested in how a group of, say, 100 judges from across the political spectrum would've ruled on cases that were already decided by juries. Are they more or less likely to be swayed by X/Y/Z? Where's CHIRP's resident legal scholar so that we can find answers to these questions?? If push comes to shove, though... I think I'd take my chances with the solitary judge.

One last note: I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the crime documentary The Staircase, made by the same two French filmmakers who produced Murder on a Sunday Morning. Readers out there -- try not to find out too much info about this case ahead of time. Just watch.

Did you see the movie? Want to add to the conversation? Leave a comment below!

Next entry: CHIRP Radio Best of 2017: Dylan Peterson

Previous entry: Coming Soon: CHIRP Radio’s Best Albums of 2017!

comments powered by Disqus