Now Playing

Current DJ: Jim K

White Denim River to Consider from D (Downtown) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

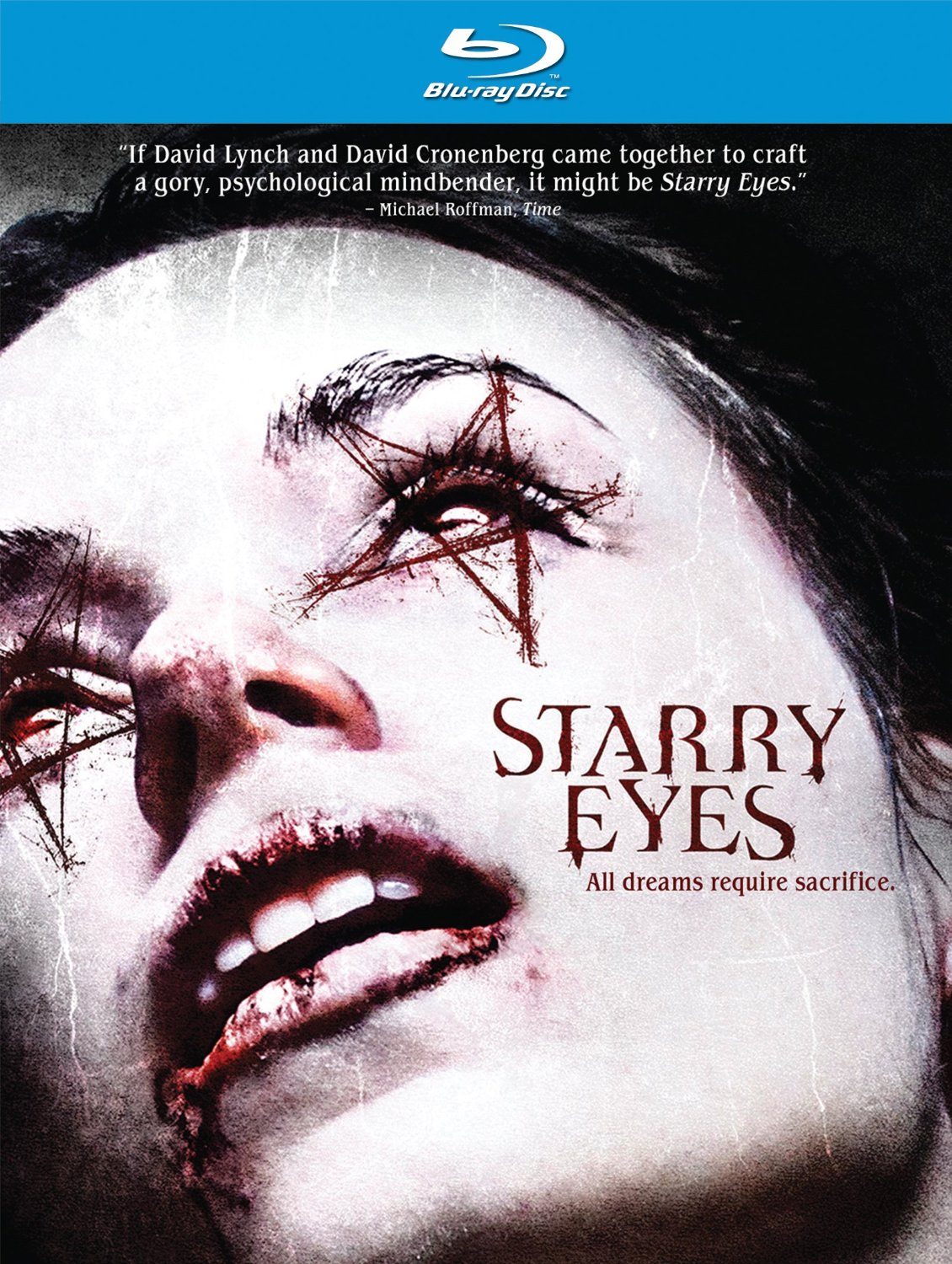

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the horror film Starry Eyes.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Sarah is a young woman living in Hollywood and hoping to make it to the big time as an actress. She spends her days working a crappy day job as a waitress while squeezing in auditions and hanging out with her like-minded social circle of wannabe film-makers.

One day, Sarah lands an audition for what sounds like a low-rent horror movie flick. It turns out to be the most intense experience of her life, and it could lead to bigger things...if she’s willing to pay the price. Soon, she will have to decide how willing she is to undertake the physical and mental transformation asked of her, and also what to do about the “friends” who might be holding her back.

Partially funded by a Kickstarter campaign, Starry Eyes was a hit at South-by-Southwest in 2014. It’s got an indie-film sheen with a slasher-movie soul. I thought Alex Essoe did a wonderful job in the lead role, transmuting her ambition into frustration and rage that fuels her character through a (to put it mildly) drastic transformation. The supporting cast is also good, and the makeup and effects are disturbingly realistic.

But this film struck me as more than just a well-crafted exercise in horror. I thought the film also did a very good job of allegorizing both the idea of “making it” in Hollywood as well as the economic outlook faced by many Millennials in the US in the 21st century.

I finished watching the FX miniseries Feud: Bette and Joan a couple of weeks ago. That series was advertised as a campy send-up of the animosity between legendary actors Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, but it ended up being a sharp, detailed portrait of the underbelly of celebrity.

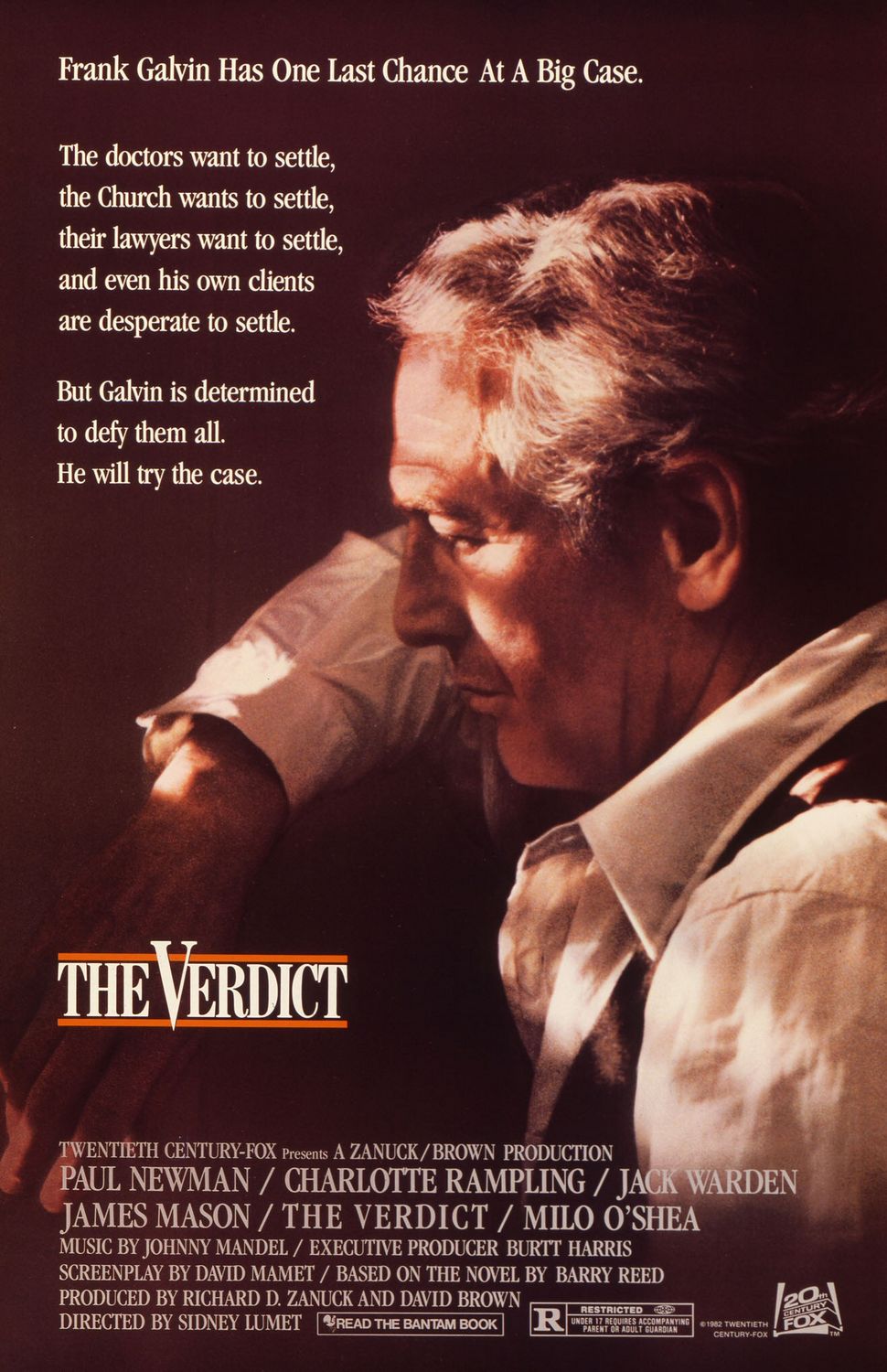

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the Paul Newman legal drama The Verdict.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

Kevin:

Why do courtrooms make for perfect Hollywood environments?

1) The guts of the action is contained within one arena.

2) The proceedings allow for star thespians to showcase their dramatic chops through impassioned arguments and clever questioning.

3) As in sports, cases usually offer up clear winners and losers -- with an added benefit of suspense right before the jury announces a verdict.

I grew up watching Perry Mason telemovies -- where Mason would not only successfully defend his own clients, but also reveal the trueculprits through his infamous "Isn't it true..." interrogations. It's interesting how criminal defense attorneys are generally not held in high regard by the much of the public in real life... the unfortunate perception is often that they're defending crooks, right? But in fiction, they have made for some rather popular big-screen heroes. (To Kill a Mockingbird, A Few Good Men, etc.)

Another segment of the legal profession that's generally treated with derision? Malpractice lawyers, often considered a subset of the "ambulance-chaser" contingent whose growing presence has inspired heated debates on tort reform. In 1982's The Verdict, Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) is one of those attorneys, although he's clearly down on his luck and spending far more time playing pinball at the local pub than working on cases.

Frank has been offered one last lifeline from longtime colleague/mentor Mickey (Jack Warden) -- a case where a pregnant woman was given an anesthetic during childbirth, wound up vomiting due to a mixup re: her last meal, and has since become comatose. It's an open-and-shut settlement; the Archdiocese running the Boston hospital doesn't want the negative attention of a trial, and Galvin stands to clear a healthy sum with his 1/3 cut of the payoff.

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the action heist movie Baby Driver.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Clarence:

Baby Driver (written and directed by Edgar Wright) is the story of Baby (played by Ansel Elgort), a young man who knows two things – music and driving cars. He’s exceptional at the latter, a talent that results in him working for a crime boss (Kevin Spacey) who uses him to make sure his crews make a clean get-away from their heists.

Using his MP3 player to create a soundtrack for his life, Baby thinks he’s on the way to finishing his criminal obligations. But things start to go off the rails when he meets Debora, a waitress who shares his longing for the freedom of the open road. Before they can ride off into the sunset, they’ll need to figure out how to get away from the danger posed by Baby’s job and his co-workers.

I liked this movie a lot. It was just a great way to spend a couple of hours in a movie theater. There are times when I leave a theater more tired than when I came in due to boredom or frustration with what I just watched. Not this time. This movie gave me energy instead of taking it from me.

The action sequences are fluid and fast. The soundtrack is an expertly-curated mix of ‘50s-‘70s Rock. The sound design is fantastic, especially in how it merges the music to the action and even the thoughts in Baby’s head. It’s got a kind of blissful romance that’s not featured in movies much anymore. And I liked that I truly did not know how the story was going to end.

The performances (including co-starring roles from Jamie Foxx, John Hamm, and Eiza González) are all excellent. Everyone understands the kind of movie they’re in and plays their roles just right. I’m hoping I never come across one of the inevitable “Here’s 10 Mistakes in Baby Driver” Internet essays that are sure to appear. This is a kind of story I feel doesn’t need to be dissected for realism.

The movie seems to be doing well by word of mouth. My first question to you, Kevin - Is there such a thing as a “Summertime Flick?” I would like to think this is a kind of movie that would be great regardless of the season, but does running it during the summer add anything, or is that just an outdated marketing device?

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week, the discussion is about the HBO miniseries Big Little Lies. This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

Kevin:

Kevin:

Horror Vacui -- translation: "Nature abhors a vacuum," attributed to Aristotle

I'm a big believer in the concept of "hedonic adaptation," the idea that everyone has their own equilibrium with regards to happiness (or unhappiness, as the case may be), and that external events don't have much of a lasting impact in either direction. Fundamentally miserable folks who win the lottery are going to be just as disgruntled a year later, whereas more cheerful sorts who weather tough times will eventually rebound to their original dispositions.

Taken another way, it also means that we generally stop appreciating the especially good things in our lives, even if those involve, say, living in mansions which overlook the Pacific Ocean. If you're prone to petty jealousies and itching for fights, why should such idyllic environs get in your way? Such are the inhabitants of Monterey, CA* in HBO's miniseries Big Little Lies.

[*Of course, this didn't deter me from googling "apartments Monterey CA" as soon as I finished the series. And from looking up the weather -- highs between 60 and 72 year-round, my friends.]

At the outset of BLL, it's clear that something has gone horribly wrong. There's been a death at a local gala. A police investigation is underway. Townsfolk are being interviewed. These interview snippets -- which pop up throughout the entire series -- are quite a clever way at setting up the players involved.

Here, the women rule the roost, from the feisty, vindictive Madeline (Reese Witherspoon, very much in Election's Tracy Flick mode) and her nemesis Renata (Laura Dern, as a take-no-prisoners corporate bigwig), to the graceful, beguiling Celeste (Nicole Kidman) and newcomer Jane (Shailene Woodley). All are moms with children in the same first-grade class, where an incident on the first day of school triggers an escalating chain of events.

Unsurprisingly, considering the all-star cast, the series is a showcase for some serious acting chops -- with Kidman's Celeste leading the way as the Woman Who Seemingly Has It All... but is hiding dark secrets behind closed doors. Her interactions with husband Perry (Alexander Skarsgård) and therapist Amanda (Robin Weigert) are among the most powerful of the series, albeit brutally so. How much of a facade does each of us present to the outside world?

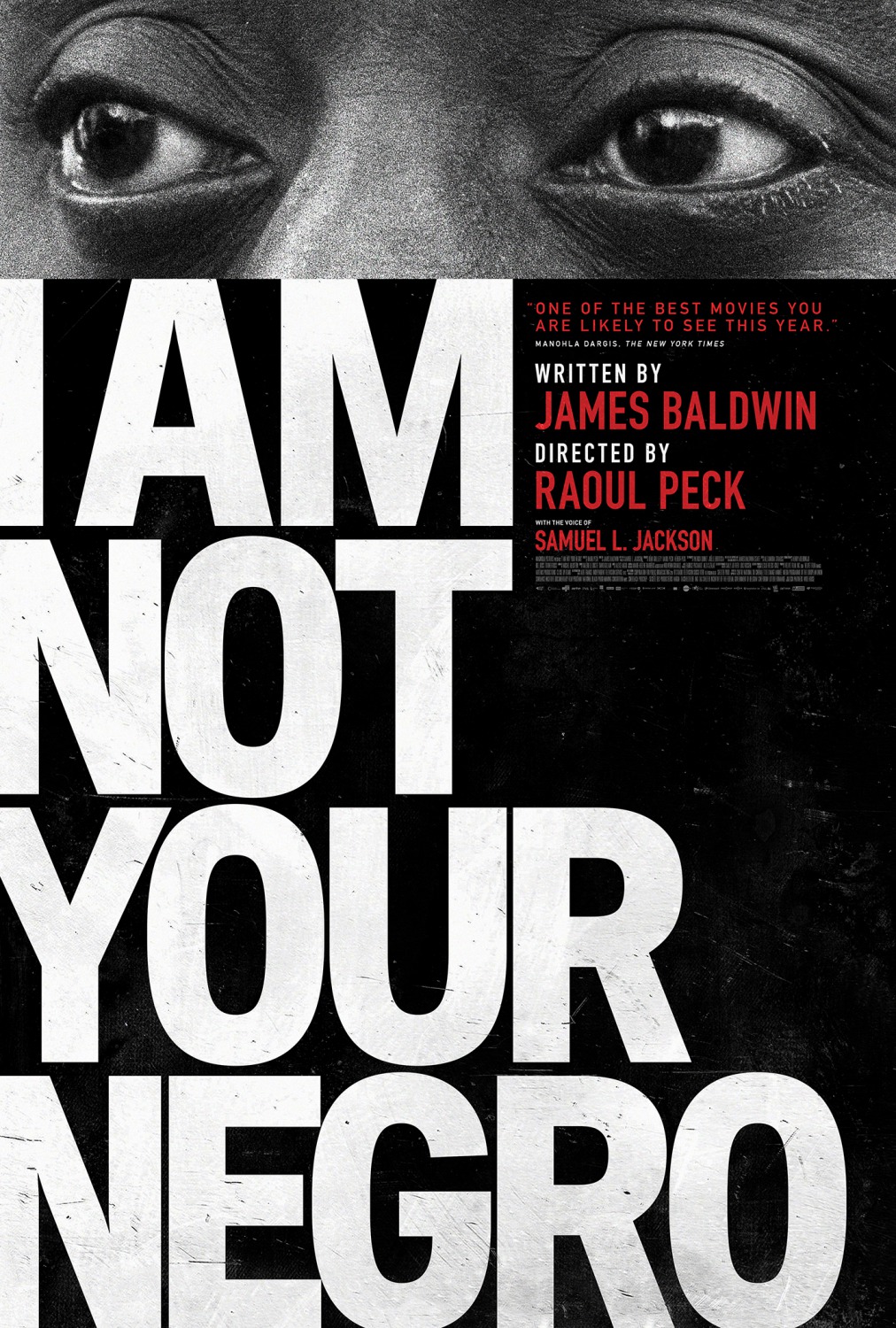

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week, the discussion is about the James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro. This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

Kevin: Clarence, while digesting the myriad of themes in I Am Not Your Negro, I got the feeling that director Raoul Peck had enough material here for three documentaries, not just one? The film pinballs between the life of writer James Baldwin (whose unfinished manuscript Remember This House formed the backbone of the movie) and his recollections of assassinated civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. In addition, we're also treated to a powerful, disturbing visual collage ranging from Hollywood films to newsreel protest footage -- one which shows us just exactly what white Americans thought of their black countrymen during the early/mid-20th century.

Kevin: Clarence, while digesting the myriad of themes in I Am Not Your Negro, I got the feeling that director Raoul Peck had enough material here for three documentaries, not just one? The film pinballs between the life of writer James Baldwin (whose unfinished manuscript Remember This House formed the backbone of the movie) and his recollections of assassinated civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. In addition, we're also treated to a powerful, disturbing visual collage ranging from Hollywood films to newsreel protest footage -- one which shows us just exactly what white Americans thought of their black countrymen during the early/mid-20th century.

It's that collage which stuck with me the most. How far have we come as far as racial reconciliation? Peck's juxtaposition of police-brutality videos of yesteryear with today's social unrest seems to suggest that we haven't traveled very far at all. While whites no longer line up with signs (and worse) to oppose the integration of schools and communities like they did in decades past, are we not still a largely segregated society, albeit informally?