Now Playing

Current DJ: CHIRP DJ

Cristóbal Avendaño & Silvia Moreno XXI - Espera I from Lancé esto al otro lado del mar (self-released) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

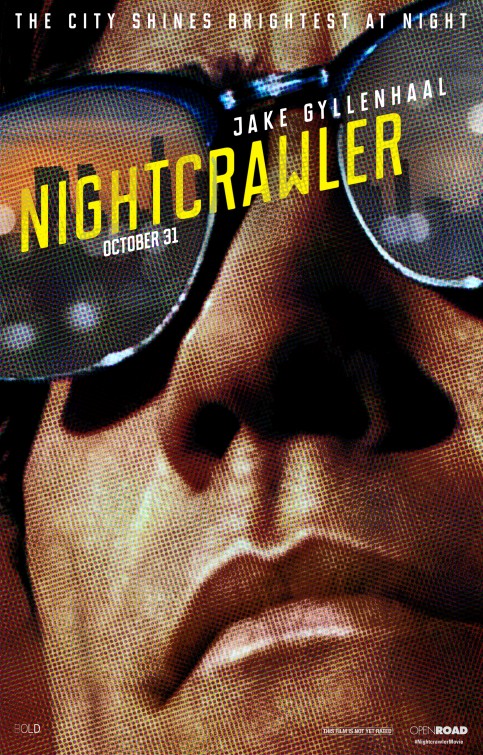

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is The Jake Jake Gyllenhaal thriller Nightcrawler.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Clarence:

Clarence:

"If it bleeds, it leads."

If you watch movies and/or TV long enough, that statement will be made by someone to either condemn or praise the television news industry. Depending on who's speaking, it’s either a bite-size indictment of a business that thrives on greed and suffering, or a clear-eyed, realistic assessment of market forces and consumer demand.

I kept thinking about that phrase as I watched Nightcrawler, the story of Lou Bloom and his rise to the top of his chosen profession. Bloom isn’t what you’d call a social person, but he has drive, ambition, and knowledge (the latter of which is mostly gleaned from the internet). After coming across a horrible accident scene one evening, where freelance camera crews swoop in to sell gruesome shots to the highest bidder, Bloom finds his True Calling. With a little help from his near-homeless assistant Rick (Riz Ahmed) and struggling morning news producer Nina Romina (Rene Russo), he’s going to make something of himself… no matter what it takes.

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 2008 crime drama Frozen River.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin: While I can count many, many tiers of wealth separating my own lifestyle from that of Pure Opulence, a middle-class existence seems mighty lavish when compared to the dreary day-to-day survival of Frozen River. Strap yourselves in, folks... and be thankful that you have more than Tang and popcorn awaiting you for breakfast in the morning.

Ray Eddy (Melissa Leo, in an Oscar-nominated performance) lives with her two sons in a battered trailer at the edge of civilization in snowy, upstate New York -- and her deadbeat husband has just absconded with what would've been the down payment on a shiny, new "double-wide" mobile home. Christmas is coming, the cupboards are bare, and through happenstance, Ray stumbles upon Lila (Misty Upham), a member of the nearby Mohawk tribe. Lila ekes out her own living by helping to smuggle illegals across the Canadian border via the frozen St. Lawrence River.

The two women become partners out of financial desperation, and each successive trip feels like another round of Russian Roulette. Is this the time when the icy river cracks? Are the state troopers wise to the whole operation? And what happens when Pakistanis show up to be smuggled, as opposed to the customary Mexicans and Chinese?

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week, the discussion is about the theme of urban dystopia as portrayed in American movies. . This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

Kevin: "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here..." might as well have been posted at the entrances of America's big cities during the 1970s. Crime skyrocketed in metropolitan areas across the country during this era, and rampant arson famously turned New York City's Bronx into such a war zone that it even warranted an impromptu visit from President Jimmy Carter near the end of the decade. And of course, Hollywood capitalized on these fears by putting its own spin on the story of urban blight*. Who were we afraid of? And who would protect us?

Kevin: "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here..." might as well have been posted at the entrances of America's big cities during the 1970s. Crime skyrocketed in metropolitan areas across the country during this era, and rampant arson famously turned New York City's Bronx into such a war zone that it even warranted an impromptu visit from President Jimmy Carter near the end of the decade. And of course, Hollywood capitalized on these fears by putting its own spin on the story of urban blight*. Who were we afraid of? And who would protect us?

[Even without the threat of bodily harm, 1970s cinema does not paint New York City in a flattering light. The French Connection, Mean Streets, Taxi Driver... these films weren't exactly commissioned by the city's tourism bureau.]

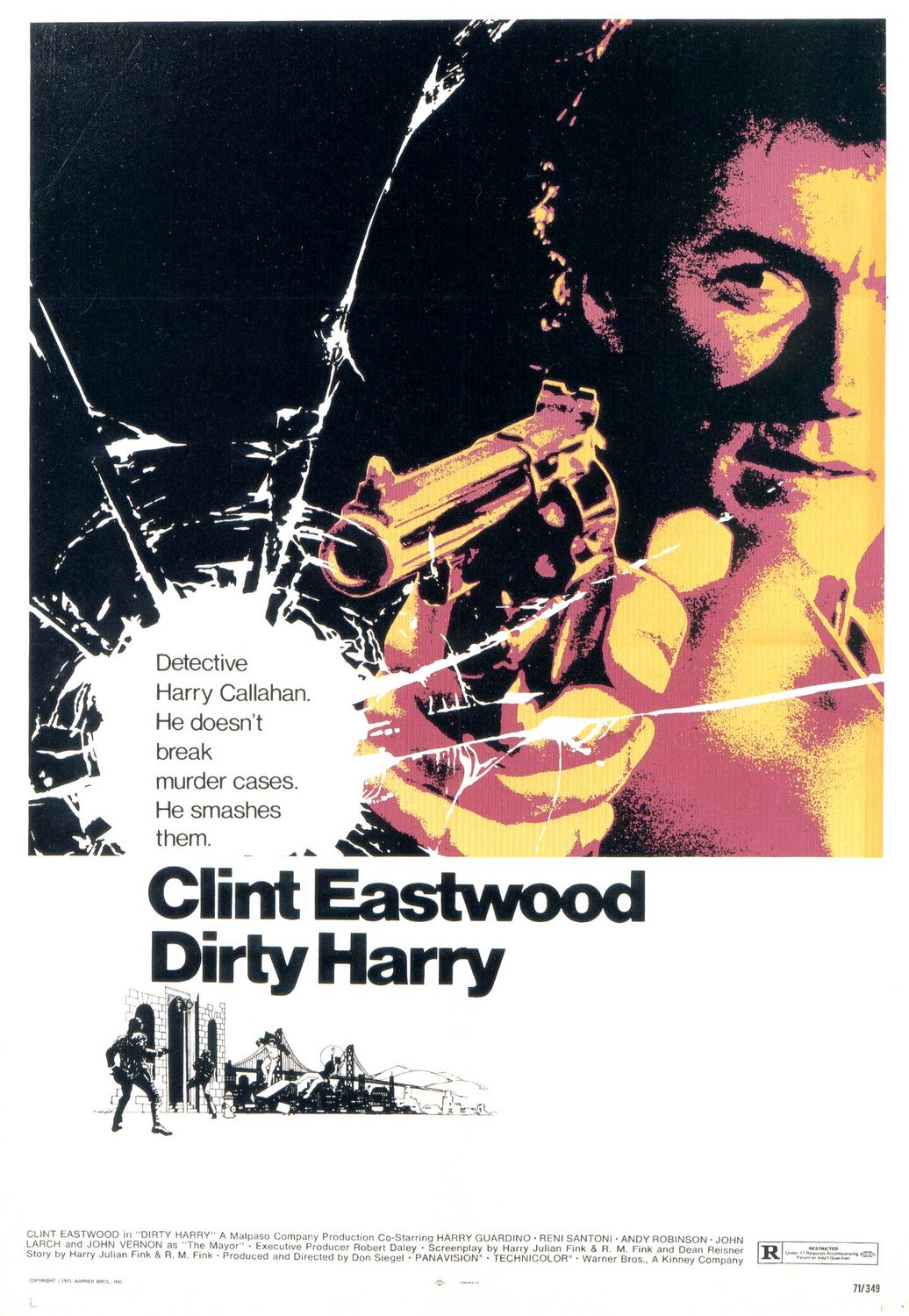

In 1970, the Clint Eastwood classic Dirty Harry introduced a cop (Eastwood's Harry Callahan) who was battling his own administration as much as the crooks on the street; those pesky rules and regulations were interfering with his ability to deliver frontier-style justice. By the time that Death Wish appeared four years later, the police had become virtually impotent and had seemingly surrendered the streets to gangs.

In Death Wish, liberal Paul Kersey (played by Charles Bronson in a career-redefining role) becomes a hardened, gun-toting vigilante after his family is brutally attacked by street thugs. Critics were horrified for what they saw as a promotion of antisocial behavior, but audiences ate it up... though unfortunately, that meant a long line of sequels which grew more bizarre with each iteration.

[Death Wish 3 is firmly in the "So Bad It's Good" camp -- even just the trailer is pure absurdist comedy. And for more madcap humor, check out the trailer for the cult film Class of 1984, about out-of-control high-schoolers. The "school beset by wild youth" theme has been a popular subgenre here -- stretching back from Blackboard Jungle in 1955 to Lean On Me, Dangerous Minds, and The Substitute in the '80s and '90s.]

With no abatement in sight by the end of the '70s, what did people envision coming down the pipe in the future? Enter John Carpenter's Escape From New York, where the America of the future decides to cede Manhattan entirely to criminals, and walls off the borough like a leper colony. The President's plane gets hijacked, crash-lands inside the prison, and it's up to one renegade (Kurt Russell's Snake Plissken) to get him out. Fantastic premise, though the finished product will probably come off as a bit sluggish and more than a little dated today. (Clarence, I know we disagree on this!) Nevertheless, it was a brilliant reflection of the zeitgeist of the time. What do we do about crime?

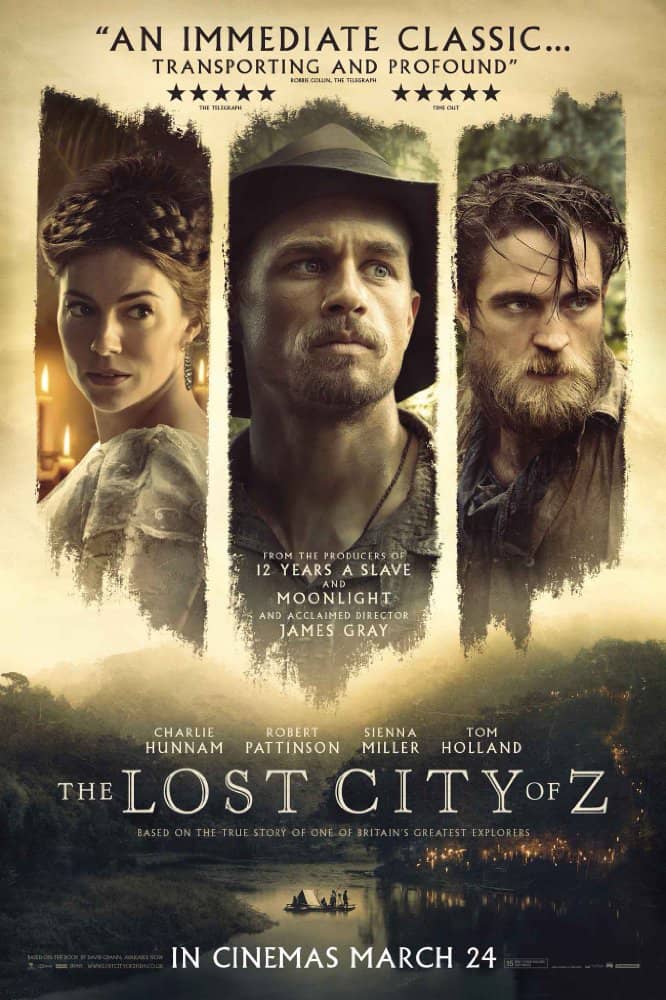

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the movie The Lost City of Z. This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

Clarence: This week we’re having a look at the story of Percy Fawcett, a military officer and explorer who became a minor celebrity in the UK and US due to a series of expeditions he made to the jungles of Brazil. In 1925, Fawcett and his eldest son disappeared while searching for the Lost City of Z (pronounced “Zed” by the Brits, so I will too), a place Percy was convinced held the remains of an ancient, vibrant civilization of native South Americans.

Clarence: This week we’re having a look at the story of Percy Fawcett, a military officer and explorer who became a minor celebrity in the UK and US due to a series of expeditions he made to the jungles of Brazil. In 1925, Fawcett and his eldest son disappeared while searching for the Lost City of Z (pronounced “Zed” by the Brits, so I will too), a place Percy was convinced held the remains of an ancient, vibrant civilization of native South Americans.

The movie is based on David Grann’s NY Times best-seller The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. We’re not dealing with an Indiana Jones fantasy here, but a serious interpretation of a historical figure. As such, I feel it misses several marks.

Structurally, the film has some problems. I’d say the overall pacing is “stately” and “measured” (polite ways of saying “dull”). At the same time, the film tries to dramatize more than 20 years of Percy’s life in one 2+ hour film, which results in a lot of narrative fast-forwarding. For example, there are several sequences that show the arduous journeys up river, the explorers barely staving off starvation, disease, and attacks from natives. Then, when they hit their objective, there’s a smash cut to the characters back in England. The editing choices make it seem that it’s a lot easier to get out of the jungle than to get in.

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the film Hell or High Water. This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

WARNING: MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD...!

WARNING: MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD...!Kevin: While watching Hell or High Water, I was thinking that it's been quite a rough stretch for bankers... but banks have always taken abuse in popular culture, haven't they? They're pretty easy targets for a variety of reasons:

1) By definition, they're symbols of wealth and power.

2) They're largely faceless* institutions -- and like corporations, they tend to have a robotic, uncompromising element to them. Like a Terminator of finance. Good ol' Tywin Lannister of Game of Thrones explained it best when discussing the Iron Bank of Braavos: "You can't run from them, you can't cheat them, you can't sway them with excuses. If you owe them money and you don't want to crumble yourself, you pay it back."

[* Not always, of course. Mr. Potter from It's a Wonderful Life was not a popular man in his town. And Ebenezer Scrooge of A Christmas Carol was so infamous that his last name became synonymous with being miserly.]

3) Banks tend not to be staffed with Dudley Do-Rights who are trying to better society. When it comes to Hollywood, bankers always seem to be trying to put one over on you.

4) Historically, moneylending hasn't exactly been viewed as a noble profession. (And of course, mafia loan sharks go one step further by adding an element of violence to the proceedings.)

I struggle to think of one positive depiction of someone working in the financial industry -- does the cop who snared Al Capone with tax evasion charges in The Untouchables count?

That brings us to Hell or High Water, where brothers Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster) are attracting the attention of Texas Rangers (led by Jeff Bridges as Marcus Hamilton) by staging a series of small-time bank robberies. Since the thefts are minor, the witnesses are few, and the proceeds are quickly laundered via casino chips, the duo seems to be faring well. But of course, in typical Hollywood fashion, Tanner is a bit of a hothead who starts taking needless risks that threaten the whole enterprise.