Now Playing

Current DJ: Alex Gilbert

Japanese Breakfast Orlando in Love from For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women) (Dead Oceans) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

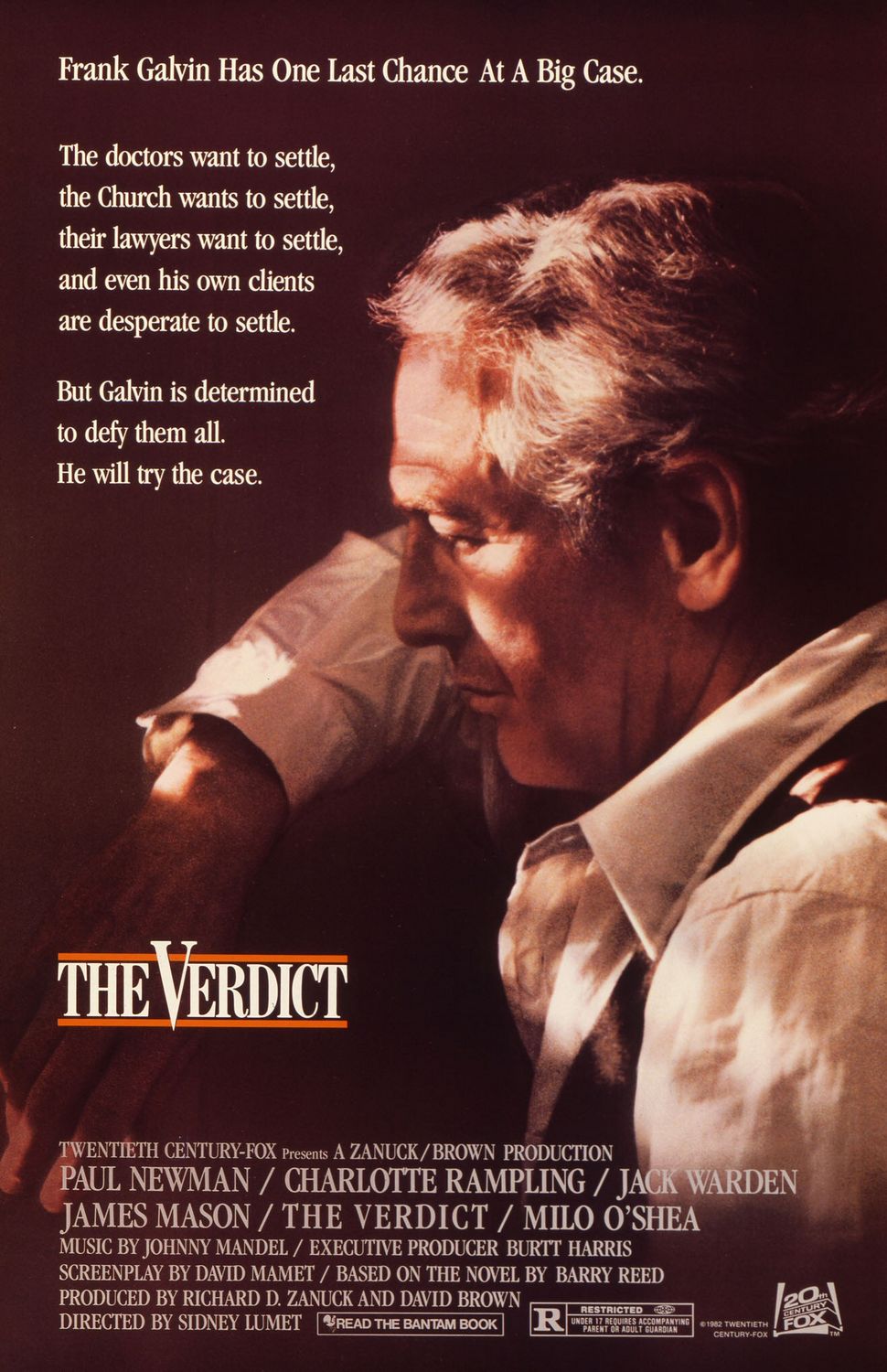

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the Paul Newman legal drama The Verdict.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

Kevin:

Why do courtrooms make for perfect Hollywood environments?

1) The guts of the action is contained within one arena.

2) The proceedings allow for star thespians to showcase their dramatic chops through impassioned arguments and clever questioning.

3) As in sports, cases usually offer up clear winners and losers -- with an added benefit of suspense right before the jury announces a verdict.

I grew up watching Perry Mason telemovies -- where Mason would not only successfully defend his own clients, but also reveal the trueculprits through his infamous "Isn't it true..." interrogations. It's interesting how criminal defense attorneys are generally not held in high regard by the much of the public in real life... the unfortunate perception is often that they're defending crooks, right? But in fiction, they have made for some rather popular big-screen heroes. (To Kill a Mockingbird, A Few Good Men, etc.)

Another segment of the legal profession that's generally treated with derision? Malpractice lawyers, often considered a subset of the "ambulance-chaser" contingent whose growing presence has inspired heated debates on tort reform. In 1982's The Verdict, Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) is one of those attorneys, although he's clearly down on his luck and spending far more time playing pinball at the local pub than working on cases.

Frank has been offered one last lifeline from longtime colleague/mentor Mickey (Jack Warden) -- a case where a pregnant woman was given an anesthetic during childbirth, wound up vomiting due to a mixup re: her last meal, and has since become comatose. It's an open-and-shut settlement; the Archdiocese running the Boston hospital doesn't want the negative attention of a trial, and Galvin stands to clear a healthy sum with his 1/3 cut of the payoff.

But Frank's conscience gets the better of him, and his desire to expose the negligence of the doctors involved leads him to decline the settlement and head to trial. And then we see just how lopsided the battle lines are. While Frank and Mickey toil away in a ramshackle office, a small legal army is assembled by charismatic lead counselor Ed Colcannon* (James Mason), whose every affection just screams Old Money. Key witnesses for the plaintiff soon start disappearing, as the defense brings its considerable resources to bear.

[* Mason's Colcannon seems to cut from the same cloth as John Houseman's stuffy Charles Kingsfield in 1973's The Paper Chase... and then I read that Mason had originally been considered for that role!]

Along the way, Frank picks up Laura (Charlotte Rampling) at the aforementioned pub; she provides some key Tough Love support, along with an enigmatic background... and then some.

The Verdict earned Oscar nominations not only for Newman and Mason, but also for director Sidney Lumet and screenwriter David Mamet. Lumet frequently targeted institutional corruption in his pictures, from law enforcement (Serpico), to the media (Network) and politics (Power). Here, he takes on the medical establishment, and questions the prevailing attitude that medical experts with fancy degrees are beyond reproach.

Clarence, The Verdict was released in '82, but seemed much more in line with 1970s cinema, not just with its pacing (a bit deliberate at times) but also its presentation. How did you feel about the pacing of the film? Do you think it's aged well? Any thoughts on the depiction of women and minorities in the film? And how does it hold up when compared with your other favorite courtroom dramas?

Clarence:

We discussed the concept of urban dystopias a few weeks ago. I got to thinking about that theme while watching The Verdict.

This story takes place in an environment where the Haves and Have-Nots are clearly dug in to their separate corners. The Church, The Doctor's Office, and The Law, three of society's sacred institutions, are entrenched in their own self-interest. (This movie made the Catholic church look more like the Mafia than any I can remember.) Those below a certain socioeconomic level who don't play along or keep quiet can expect swift and brutal reprisal. Those who do cooperate get whatever crumbs the powerful decide to give hand out.

Most importantly, you have a populace that's too scared, defeated, cynical or grief-stricken to do anything about it. It seems most of Lumet's movies involve someone critiquing a societal weakness and deciding to at least try to change things. Lumet's direction and the superb cinematography take the audience deep into a system whose complexity and scope is matched only by the puppet masters' callousness toward the suffering of a single, unimportant human being. The act of going up against a machine designed to do anything except get to the truth makes Galvin's efforts all the more heroic, even as his fatal flaws are put under a brighter spotlight.

Mamet's dialogue is also fantastic. I liked the economy of words and directness of the language. Any screenwriter who can make characters sound like they're actually talking to each other instead of exchanging lines is worth their weight in gold. The way Mamet and Lumet place silences and pauses at key points is also very well done, such as when Galvin first meets the doctor he recruits as an expert witness. "Oh my God...you're black," Newman silently says with his facial expression, and that's all that's needed. Boston in the late '70s/early '80s was as bad as any place in the South as far as racism is concerned, and the film does a good job of depicting the contempt always lurking just under the surface.

I was a bit surprised by the rawness of Frank and Laura's story arc, but it was in keeping with the film's overall tenor. Again, there's no need for a lot of dialogue as they gradually discover the truth about each other.

The elements of this film hold up very well, even in a different cultural climate such as ours. The pacing held up too, which can be tricky for this kind of movie. I'm curious - which parts did you think dragged?

I was trying to think of other courtroom movies I've seen, and only a few come to mind. The Bounty (The version with Anthony Hopkins) uses Captain Bligh's trial as a frame for the story. The only other one I can think of is A Few Good Men, one of Tom Cruise's better performances, IMO. I've never seen a complete episode of Perry Mason, but that character is so iconic in American entertainment that I feel like I have an affinity for him.

Are you a fan of TV shows like Law & Order? It seems like those kinds of programs, along with the 24-hour news cycle, have taken over the courtroom drama "genre" from the movies. And what do you think of Paul Newman? It seems to me like he doesn't get nearly as much attention as the Clint Eastwoods of the world, but he's one of the best stars of the '60s and '70s eras. Would it be fair to call Newman underrated in this day and age?

Kevin:

Is it sad that, in my younger days, I primarily associated Paul Newman with pasta sauce, lemonade, and popcorn instead of movies? Can I blame my family's grocery-shopping decisions for this one? (Sorry, mom...) The Verdict marks just the fourth Newman film I've seen, joining Cool Hand Luke, The Sting, and Road to Perdition. I've enjoyed all those films, as well as Newman's performances, though they're also movies I've never been chomping at the bit to revisit.

You mentioned Clint Eastwood, and I thought about why Clint is seen much more as an landmark figure. Eastwood portrayed two iconic characters -- The Man with No Name, and Dirty Harry. Both exuded the same tough-as-nails, "strong silent" persona to the point where as soon as you see Eastwood's face on screen today, no matter what the project, the message is clear: evildoers beware. In contrast, Newman has more of an Everyman quality? (Of course, so does Tom Hanks, though Newman's heyday was prior to the blockbuster era.)

I'd also add that Eastwood was a visible Hollywood presence for a much longer period of time. He not only had starring roles into his late-70s (the last being in 2008's Gran Torino), but also directed a slew of Oscar-nominated films in his later years as well, with 2014's American Sniper coming at the age of 84.

[Can we forgive Clint for his bizarre Obama Chair performance during the 2012 GOP Convention? I'd vote to give him a pass here.]

Are there any Newman films you'd list among your favorites? And does he "carry" The Verdict the way a Hollywood superstar carries a film? There's one moment where I think he does: Galvin's powerful closing argument to the jury.

It's interesting that you bring up Law & Order -- while I generally dig courtroom dramas on screen, I've never watched any weekly courtroom procedurals, from L&O to LA Law to The Practice. Mainly because I simply haven't kept up with network television for decades? However, I'll mention two courtroom documentary series that I've loved: Making a Murderer and The Staircase, the latter of which is my all-time favorite doc of any stripe.

However, with both of those series, our attention is placed solely on the cases -- in films like The Verdict and A Few Good Men, there's always a backstory and side-plots involved. The lead attorneys in both of the aforementioned films are seeking a bit of personal redemption, and Newman's Galvin is dealing with the additional burdens of alcoholism and a failed marriage. So I guess one's Mileage Can Vary as far as this goes? It's what I alluded to as far as the pacing of the film -- I suppose I was chomping at the bit to get to the courtroom action a bit earlier.

I did enjoy, however, being privy to a slice of the opposition in Colcannon and the Boston Diocese -- as you stated well, the "Haves" in this battle. What did you think about Colcannon's "win at all costs" speech to his troops? It's at this moment where the defense slides on the Morality Chart from "admirable opposition" to "villainous." Did we need the lines of good/evil to be painted so starkly here?

[It's also clear that Galvin goes a bit outside the law as well, though not to nearly the same degree as his opponents. Suppose the defense had played "by the book" while Galvin cheated to win. Even if Galvin was in the right, how would we feel as an audience?]

Also, you brought up the analogy between the Catholic Church and the mafia -- the former has taken quite a beating in Hollywood over the years! In addition to this film, there's Spotlight, Doubt, and Primal Fear, just to name a few...

Clarence:

I think organized religion in general has a tough time of it in the movies, going all the way back to the Inquisition. Not that official religious organizations have done themselves any favors in the last few decades, on the Catholic and Protestant sides. I'm trying to think of a film where the Church is presented as an unequivocal force for good, but all I can think of are the films where Jesus Christ or one of his disciples is the main character (i.e. The Ten Commandments).

One of my favorite films of all time is The Hustler (1961). Fast Eddie Felson, Newman's character in that movie, has a lot in common with Frank Galvin. Both characters are extremely talented yet deeply flawed people who really want to do the right thing but can't seem to get out of their own way.

The Hustler, like The Verdict, also benefits from great writing and a stellar supporting cast [including Jackie Gleason and George C. Scott]. But it's Newman's show and he carries it off beautifully. I feel that actors of Newman's and Eastwood's generation had more depth than those of Tom Hanks' era. Very few of them could pull off Galvin's degree of sustained close-up suffering. It seems like what was being asked of big-time actors was different in those decades.

During the trial, when Colcannon is questioning the expert witness Glavin has hired, Colcannon makes a point of asking the doctor if he is there because he's getting paid to be there. "Yes," the doctor replies, "as are you." Colcannon quickly moves on, but that question and answer gets to the heart of what Galvin is up against, not to mention the American legal system in general.

I took exactly one law course in school. The professor for that class reminds me a lot of Mickey - extremely knowledgeable about the law while also seeming cynical about the legal profession. He once said something to the class that I still think about today - "The law has nothing to do with fairness, justice, or morality."

At the end of the day, the law is an extremely complex series of rules and procedures. Whoever can navigate those rules successfully while also (if necessary) communicating the right things to a jury wins. As with most other enterprises, the party with the most resources is the one most likely to come out on top.

And yet a desire for something resembling justice, if not justice itself, is such a fundamental part of American society that I suspect Frank would have been forgiven in the public's mind if he had cut corners to win. At least he would be playing at the same level as someone like Colcannon, with the latter's vast resources and assorted tactics. I think what might resonate more than the "how" would be Frank's inner resolve. What was more important than his career, and more important than winning, was standing up for what is right.

Did you see the movie? Want to add to the conversation? Leave a comment below!

Next entry: 2017 Pitchfork Music Festival: Day 1

Previous entry: Pitchfork 2017 Is Here!