Now Playing

Current DJ: Liz Mason

Void Pedal Parachute from Omni Colour (Fieldwerk) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

by Bradley Morgan

by Bradley Morgan

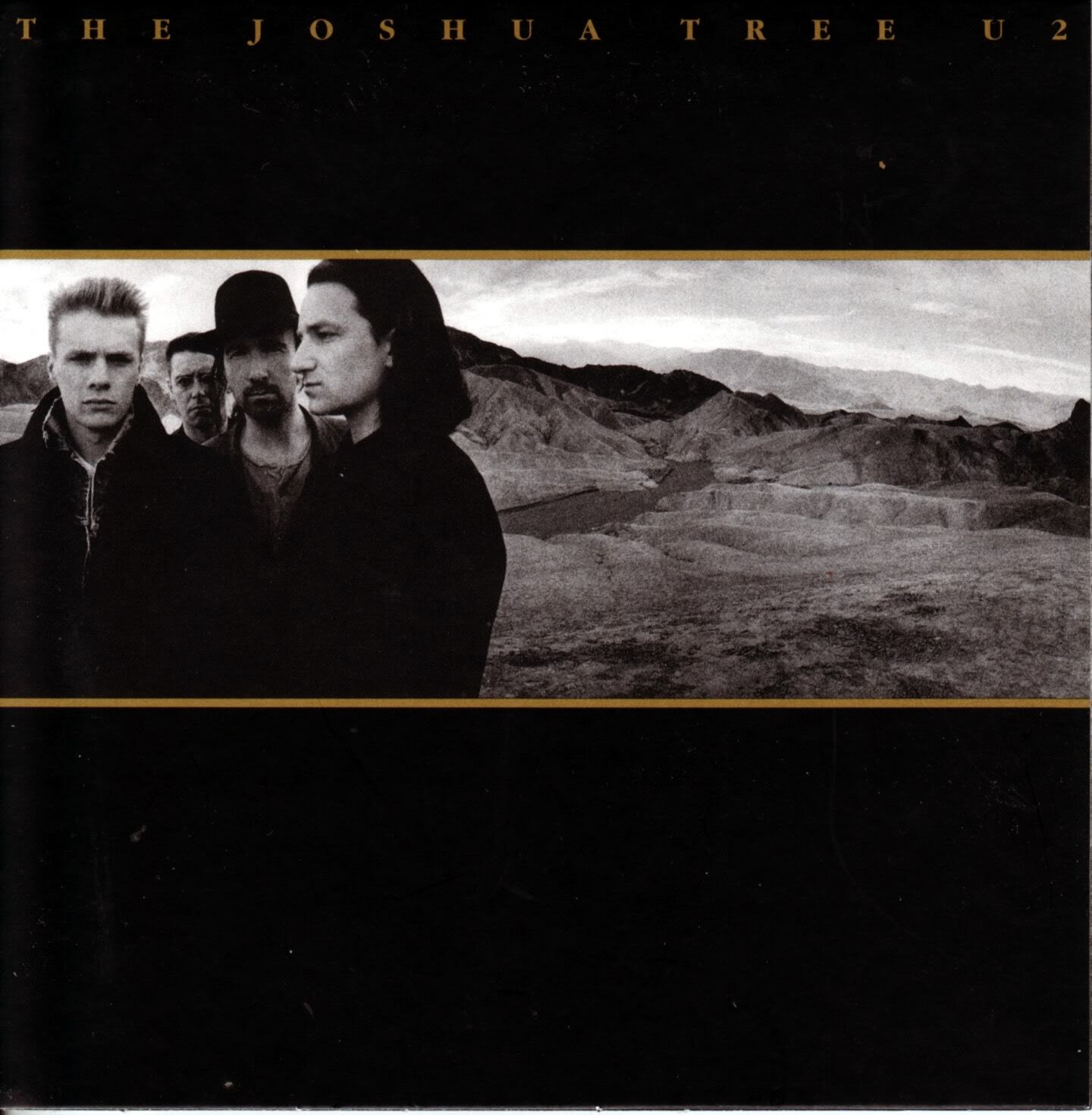

Last Saturday, I ventured out to Soldier Field to see U2 play their masterpiece record The Joshua Tree in its entirety. I had been looking forward to this show for months. I even invited my dad and he drove over six hours to experience his first U2 concert.

Of course, I had seen Ireland’s favorite sons play a few times already including a greatest hits show and a concert promoting their latest studio album. However, this tour was different. The Joshua Tree Tour 2017 was designed with duality in mind; to commemorate the past but to also understand its relevance in the present. While this show signified a nostalgic trip for some, the tour set out to make a statement about the complexities of humanity and society. In preparation for the performance, I had to go back and find out not only what The Joshua Tree meant to me as art but also what U2 represented that made them so relatable to me over the years.

My path toward U2 fandom began at age twelve back in the fall of 2000 while I was living in Alaska. Anchorage didn’t really have any record stores or cool hot spots where hipsters could browse indie music stacks and discover the next big underground thing. Not only that, but streaming media online was not as sophisticated and easy to use as it is today, plus my dad wouldn’t let me download music. So, the only musical outlets available to me were whatever played on commercial radio and the limited selections of a local Wal-Mart or FYE.

That fall, U2 released their single “Beautiful Day” and it was life-changing. The sound was big and anthemic; qualities that inspired a budding teenager who had a lot to say and demanded that he be heard. The optimism and humanity within that song truly spoke to me.

Prior to that, U2 was a band that I had only heard of before. I had seen copies of War and The Unforgettable Fire in my mother’s CD collection, but I never listened to them before because what teenager wants to listen to their parents’ music collection? I wanted something new and relevant to me right then and there, despite the irony that this exciting new addition to my life was being delivered by an already established and accomplished band.

The music itself wasn’t the only thing that made me connect with the band. This band had something else going for them, too. They were Irish. That instantly made them more relatable and meaningful to me. As the son of an English immigrant with Irish grandparents, that made U2 so much more special. A bond was established through a shared ancestry that I wouldn’t quite understand until much later.

During the summer of 2001, I took a trip to England with my mother and sister. There, we stayed with my aunt, spent time with family I rarely see, and explored London. During that trip, we would pay my grandparents a quick visit in Waterford, Ireland. The trip was a lot of fun and I had a great time visiting my grandparents, but there was a special experience I had there that I’ll always treasure. I actually got to visit my first real independent record store. Nothing like the big box retailers that were only available to me back home, but a truly authentic music retailer that specialized in releases that you wouldn’t immediately find on commercial radio.

Being 13 now and still unfamiliar with what was happening in the indie music world, I played it safe. I was in Ireland and this would be the perfect opportunity to pick up my first CD from this Irish band I recently came to love. Their studio album All That You Can’t Leave Behind became my first complete introduction to the band that would help to shape my identity from that point onward.

Fast forward to 2017 and the state of our society has deteriorated in many ways. The last 16 years have seen surprise terrorist attacks, endless military conflicts in the Middle East, an increase in institutionalized racism, and the theft of democracy surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election. These themes are at the forefront of U2’s latest tour. The Joshua Tree Tour 2017 might seem like a nostalgic cash grab, but the very same political and social issues that The Joshua Tree addressed three decades earlier have returned to threaten our peace and stability within a more globalized society. While the faces have changed, the shit still smells the same.

For anyone who knows U2, they know they have been a political band since their inception. And for those lucky enough to have seen them live, they know the passion and intensity with which they speak about politics. The show on Saturday began with an emotional and riotous rendition of “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” London was attacked earlier by ISIS terrorists and Bono was sure to reference the city along with Manchester and “the streets of Chicago” as he led the audience into a chant of “no more, no war!”

Later on in the set, Bono championed the idea of America and its role in welcoming immigrants and that regardless of where we are on the political spectrum, we cannot achieve common ground unless we achieve higher ground. This idea carried over to also express support of Syrian refugees who have been bombed out of their homes. A video of a young Syrian woman named Omaima Hoshan was featured and included footage of the Jordanian refugee camp where she currently resides. In the video, Omaima talks about America being a land of opportunity and safety. All of these elements came together to support the overall theme of the tour; the devastation and hope that America brings to the world.

In order to truly appreciate U2’s commentary on this tour and why they play The Joshua Tree in its entirety, you have to go back to the beginning. In an interview with NPR, Bono stated “There’s the mythic America and the real America. We were obsessed by America at the time. America’s a sort of promised land for Irish people – and then, a sort of potentially broken promised land.” This premise of duality became the thematic origin of the album. Under the working title The Two Americas, this contradiction between the ‘American Dream’ and ‘American reality’ encapsulated more than just class and racial conflict identified by the casual listener. America had historically positioned itself as a beacon of hope for all oppressed peoples, but ultimately betrayed them as unwitting and expendable in an increasingly divided nation.

The band’s 1987 breakthrough album was a commercial and critical smash with a sonic landscape that was unparalleled to anything else on the Hot 100 chart at that time. None of the other hit songs that year sounded like U2 in terms of sound or subtext. Part of what made The Joshua Tree so powerfully unique didn’t just lie with the music, but also with the message.

In the same interview with NPR, the Edge mused on the album’s origins by stating “Ronald Reagan was in power, and Maggie Thatcher in Britain. The miner's strike was a big issue in Britain, a lot of unrest. I think we all realized that things had almost come full circle — like the environment in which that album was written is more similar to the political environment we are in today than it has been since." The Edge’s claim that their political and social message has become relevant again in today’s political climate definitely showed through during their performance at Soldier Field. The concert was more declaration than performance.

While Bono is speaking about his perspective as an Irish person, these same broken promises have also impacted the lives of people around the world. Prior to recording the album, Bono had taken a trip to Ethiopia to understand how poverty can be sustained in the modern world. He had also witnessed fire bombings in the rebel territories within El Salvador and Central America that left bodies on the streets.

Ironically, amidst the violence and extreme poverty that the U.S. government inadvertently contributed to, the local people still worshipped the leaders that kept them oppressed. Bono recalled seeing a mural in a church in El Salvador depicting Ronald Reagan riding a chariot as if he were the Pharaoh and the locals were Israelis attempting to escape. These events stayed with the band during the recording of The Joshua Tree.

Now, in 2017, U2 sees the same troubling factors coming into play again. Since the election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the United States, systemic institutionalized oppression that only benefits the upper class white male majority has come back into state-supported fashion. The political fervor that Trump has been able to stir in his supporters have exemplified just how tone deaf America can be to people who rely on it.

Immigrants escaping from Syria struggle to find safe haven, Muslims born in this country experience violence and vitriol, and women continue to be denigrated and forced into roles as second-class citizens. With this recent tour, U2 makes a grand statement out of a timeless idea, as Bono states, that “America is an idea that belongs to people who need it most.”

Over the last few months, I’ve revisited The Joshua Tree a lot. The media outlets covering the 30th anniversary as well as the promotion behind the tour has me really excited and motivated to break the album down in ways I hadn’t considered before. I wasn’t yet born when the album was released, so any understanding I have of the album being a political statement at that time can only come through research.

While both Bono and the Edge feel the problems they addressed in 1987 are resurfacing in 2016, I had to consider what that really meant. When I bought the album at the age of 20 in 2007, the world was a vastly different place. That was a time that I specifically experienced and remember. Now, a decade later, I had to consider how The Joshua Tree meant different things over the years but managed to still be so timeless and relevant in its message.

The opening track “Where the Streets Have No Name” starts with an epic delayed guitar arpeggio that repeats for newly two minutes and thusly cements its legacy as one of the great guitar songs of all time. While the band has been asked numerous times over the years about where exactly these streets are, the meaning of the song is much more metaphorical than that. The song is a statement from Bono that one’s own identity and class can be determined by what street a person lives on; a notion suggesting that one’s own geography dictates their worth and role in society.

When considering this in the context of modern social issues within the United States, it can be applied to whole communities ravaged by poverty as a result of a system segregating whole races of people through complex government policy, gerrymandering, and bureaucracy. Even when walking through large cities, the cultural and commercial makeup can change block by block. The lines separating race and class are as hard and defined as city streets. You can literally stand amongst privilege on one side and look into the eyes of the invisible on the other.

“I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” is a gospel song that connects U2’s spirituality with the soulful melodies of American roots, soul, and gospel music. When writing this song, Bono expressed that he was interested in spiritual doubt. The narrative of the song concerns seeking a high power. Whether that is love or a deity of some sort, the song embodies one’s struggle to overcome obstacles to seek fulfillment.

Though many may not achieve that by finding what they seek, the heart of this song is about the journey. For many, the end goal is safety and security. Currently, this is a difficult time for refugees and immigrants seeking peace in the United States. As the current administration shifts policies to a white nationalist identity, freedom is denied to those who need it so desperately. It is a difficult and unimaginable journey, but they are driven by hope despite doubt.

The band strays away briefly from the themes established in the first two tracks to focus on something more personal. Up to this point, the band struggled with the fame and lifestyle typically associated with rock stars. The Joshua Tree was exploding on the charts and “With or Without You” became their first number one song on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. As the band became bigger, more and more were the members’ lives changing. Bono had been married for several years to a childhood sweetheart and was struggling to balance his marital responsibilities with the freedom and excess of a rock and roll life on the road.

While U2 had visited and toured America before 1987, those trips were much smaller. Seeing the country and the gothic beauty of the deserts between playing stadium after stadium certainly put Bono in a strange headspace as this promised land opened itself to this unsure Irishman. It is a song about dealing with the excess that new and exciting opportunities can bring.

However, the personal themes inherent in the album were not just confined to the relationships and transitions the band was experiencing, but it also applied to incidents they witnessed firsthand. Kicking off with power, authoritative drums, “Bullet the Blue Sky” is one of the more raw and emotional tracks on the album. It features a harder rock sound and a poetic monologue from Bono about American jet fighter planes destroying the lives of local women and children in the villages of Nicaragua and El Salvador.

Bono had toured the area in 1986 and witnessed the devastation and displacement caused by American military intervention. The anger Bono felt during this trip carried over into the studio when recording the track. “It upsets me as a person who read the Scriptures,” Bono said, “to think that Christians in America were supporting this kind of thing, this kind of proxy war because of these Communists.”

What Bono is criticizing is blatant hypocrisy which has become a serious and arrogant problem within the last year. In the last year, the American people have been duped into fighting a war on facts fueled by despotic ideology. The new phenomenon of “alternative facts” and “fake news” have emboldened politicians to compromise their core values and beliefs to pursue initiatives that negatively impact their constituents. These leaders in our country who have sold out wear their hypocrisy and lies as a badge of honor and their supporters applaud them for that.

As U2 become a bigger force in the world of music and politics addressing international crises fueled by American intervention, they still don’t forget their roots and the problems that plague their homeland. A slow and contemplative piano ballad, “Running to Stand Still” addresses the heroin epidemic that plagued the poorer areas of Dublin in the 1980s. These communities became neglected over the years as apartment buildings became less maintained and fewer resources were made available to the children in the area.

The band had a friend who lived in one of these communities and struggled with addiction. “Running to Stand Still” is both haunting and beautiful, but carries a timeless message. Substance abuse and addiction are serious problems that can be remedied with adequate funding provided to afflicted communities in the form of clinics and social welfare programs.

The United States, though promising to offer the best opportunities to its citizens, has one of the most flawed, bloated, and expensive healthcare industries in the world. The current administration is relentlessly attacking progress made in the healthcare field by providing tax cuts for the super wealthy and leaving the middle class and poor to deal with the fall out through a reduction, or completely removal, of services and higher premiums. The threat of health and drug epidemics will increase as people seek options to deal with their pain.

“Red Hill Mining Town” was written as a direct response to the 1984 National Union of Mineworkers strike after Margaret Thatcher supported closing many of the United Kingdom’s coal mines. Public demonstrations, many of them erupting in violence, resulted in one of the most brutal conflicts in the U.K. during that era. Originally planned to be released as the album’s second single, it was shelved despite a music video being produced to promote the video.

For some reason, the band never gave the song the attention it deserved. “Red Hill Mining Town” was never even played live until the first night of this tour thirty years after its initial release. I find that a bit troubling. Not only is it a beautifully composed and performed song, but the economic themes within the lyrics make it one of the more relevant tracks from the album. Since its release, the economy has been the most important topic for many American voters.

Following billions of dollars being spent on useless wars, the biggest global market crash in history, and an atrocious tax plan proposed by the current administration, lower and middle class Americans are feeling the hurt in their wallets. Whether coming in the form of lower wages or massive layoffs, the structure of our economic way of life has dramatically changed since 1987. This current generation will be the first to be worse than their parents in terms of financial and economic stability. Unless things change, it will only continue to worsen as economic inequality aims to drive the divide between classes.

“In God’s Country” is a peculiar song for the album. Not only is it the shortest track on the album, it is the one without a specific commentary. As opposed to the other tracks which address various social, political, and personal issues, “In God’s Country” puts more focus on a visual tone. The image of desert towns populated with sad-eyed locals is so common that is comes off as a narrative trope. So much so that Bono even expressed difficulty determining if the song was about Ireland or America. While this song presents a sudden departure with the theme, it complements the album as a whole by providing a foundational aesthetic.

As U2 were exploring America and drawing spiritual connections between their native country and this alleged promised land, they were also exposed to the spirituality of American roots music. The band became obsessed with blues, soul, and gospel music to the point of incorporating elements of those genres when recording The Joshua Tree. While many more explicitly rhythm and blues tracks were left off the album, “Trip Through Your Wires” had made the final cut. Much like the previous song, “Trip Through Your Wires” doesn’t contain any specific social message. However, it is serves as a tribute to the music U2 was discovering on their American odyssey.

“One Tree Hill” was a single only released in Australia and New Zealand. The song was written as a tribute to a Māori man named Greg Carroll who had died in a motorcycle accident in Dublin. Carroll had befriended the group during an earlier tour and would eventually become a roadie for the band. Bono has described this very personal song as “a celebration of life” and that is a very important thing to consider.

A lot is happening in the world today. As terrible as things have become for the American people, it has sparked a civil uprising. People are becoming inspired to act and pursue roles in local and national government in order to make a difference. And I find that incredibly fascinating. However, I must remember that I have a life to live and I have relationships with friends and family that I need to foster because they won’t be around forever. So, I struggle with trying to determine what the balance is between being selfless and being selfish. How much can I work to better the lives of the people in this country who need it the most before it starts to impact my personal life and relationships?

I take the meaning of “celebration of life” in this song to represent one’s own life and pursuit of peace and happiness. As necessary and important it is to draw awareness to bigger issues and to solve larger problems, it is also important to focus on the things closest and personal to you.

In addition to exploring American music, Bono was also keen on discovering American literature. Inspired by Norman Mailer’s 1980 novel The Executioner’s Song as well as the Truman Capote classic In Cold Blood, “Exit” was a song Bono wrote about a serial killer. He wanted to understand “the ordinary stock first and then the outsiders, the driftwood – those on the fringes of the promised land, cut off from the American dream.”

In 1989, Robert John Bardo murdered Rebecca Schaeffer and claimed in his defense that “Exit” inspired the murder. This had a profound impact on the band in which the song caused them a lot of self-harm. “Exit” was shelved for years before returning to this current tour. Bono’s search to find meaning in what drives an outsider to act on destructive impulses are questions many today are struggling to answer.

Over the last few years, the number of mass shootings have risen; most of which committed by young white men for racially motivated reasons. Bono identifies that these individuals are outsiders who feel disconnected and abandoned by their country with no hope to achieve the prosperity they were promised. Since the election of President Barack Obama in 2008, a racist ideology has overtaken many American voters and has influenced policy in the current administration. Looser restrictions on gun purchases, decrease in mental health care access, and a general feeling of loss for white men has culminated in a violent atmosphere that affects women and minorities the most.

This phenomenon has been fueled by a sense that the white male majority are somehow losing rights or freedoms when minority groups demand equality. Unless proper measures are taken, the violence will only continue to increase.

The final track, “Mothers of the Disappeared,” closes the album on a somber note both musically and lyrically. In 1986, U2 performed during the Conspiracy of Hope tour benefiting Amnesty International. It was on this tour that he became aware of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo. These were a group of women in Chile and Argentina whose children were forcibly disappeared without a trace.

Bono had even arranged meetings with members of COMADRES who also suffered forced disappearances by the oppressive government in El Salvador and were subsequently shot at by government troops while delivering aid. The Reagan administration was intimately involved with the dictatorships even going as far to provide financial and military support. “Mothers of the Disappeared” is one of the most damning tracks on the album.

Much like with “Bullet the Blue Sky,” “Mothers of the Disappeared” aims to expose hypocrisy within the American government as well as the failures of Reagan’s foreign policies in the region. Bono reflected on his experience in these countries by saying “people would just disappear. If you were part of the opposition…occasionally they would come in and take you and murder you; there would be no trial.” His statement about events he witnessed are so incredibly profound and, for me, represent one of the most troubling circumstances facing America today.

The current administration has successfully vilified the press in an ongoing war against the media. By re-branding all criticism and negative press as “fake news,” he has directly assaulted one of the primary institutions this country was founded on. Members of the press, whose duty is to help the government maintain a system of checks and balances, are experiencing the receiving end of a well-funded and highly coordinated attack to discredit this country’s most sacred institution as part of a large scheme to dismantle it altogether.

While members of the press are not literally being forcibly disappeared in the way dissidents were in Central America, they have experienced an increase in violent assaults aimed at silencing them. Recently, a reporter was body-slammed by Greg Gianforte, a candidate for a special House race in Montana, for asking questions about Gianforte’s support of a recent proposal to the health care bill. In years before, a candidate who physically assaulted a member of the press in public would resign out of disgrace. Not Gianforte. He continued his candidacy and was even awarded the seat.

Gianforte’s supporters even rationalized his extremely violent outburst by questioning the validity of the reporter’s questions since he represented a foreign newspaper. As opposed to directly addressing the main issue, hypocrisy was allowed to take over and redirect the conversation and resulting in an undeserved win. When that kind of behavior is increasingly becoming not only accepted, but awarded, it makes me worried about the free speech in this country.

Revisiting the album in recent months has been difficult when reflecting on how prescient the themes are when applied to modern day issues. As someone who actively engages with news media, I have a thorough understanding of what is going on today. However, The Joshua Tree does not allow me to be complacent and just looking at the surface level of issues. The biting criticism and commentary requires one to dig through issues and focus on the root cause of our problems.

There’s a reason why the issues of 2017 mirror the issues of 1987. It is because we are living in divisive times where people are more concerned with what drives us apart as opposed to what brings us together. Upon knowing that, you take on a certain responsibility. You’re tasked with not just finding a temporary solution, but to help contribute to a permanent resolve; long-lasting answers that benefit from the contributions of all people of all communities no matter how large or small. Today requires everyone to become involved and elevate each other.

While The Joshua Tree continues to be a relevant work of art for its timeless message and yearning for the peace and prosperity only a promised land can deliver, the album also continues to be relevant to me on a smaller, yet more intimate level. The Joshua Tree celebrated its 30th anniversary on March 9th. This December, I turn 30 as well. While ultimately meaningless within the grand scheme of the album’s artistic scope, that shared milestone connection of having been born the same year as The Joshua Tree’s release makes it superficially more significant to me.

At 20, when The Joshua Tree entered my life, that was a more selfish time focused on getting good grades and hanging with my friends. At 30, I have fully benefited from a society that has invested so much in me, and that it’s now time to pay it back, and with interest. No longer can I be the adolescent who is content to follow. Now is the time to be the adult who leads.

However, that is not the only connection I have with the album. 2017 started off as a monumentally significant year for me. After several years of meticulous work gathering documents and a lot of money spent acquiring those documents, I was finally granted citizenship with the Republic of Ireland. Through the Foreign Births Register, I was granted Irish citizenship on the basis that my grandparents were born in Ireland. That same connection I experienced when I bought my first U2 album so many years ago transitioned from being merely symbolic in nature to something more compelling and meaningful.

My bond with this band had become less musical and more cultural; perhaps even spiritual in some respects. Just as what the Edge said about The Joshua Tree 30 years later, things had come full circle for me. Having become an Irish citizen during the 30th year of my birth and the birth of U2’s masterpiece is so serendipitous that it simply cannot be ignored.

Obtaining my Irish citizenship, however, required more than patience and money. It required serious reflection on identity and the inherent responsibilities within. Over the last few years, I became more aware about the two Americas U2 explored in The Joshua Tree. Realizing a clear distinction between the “real America” and the “mythical America,” I began to question the hypocritical standards by which many Americans governed their lives against the lives of those who wished to seek asylum or citizenship.

While these Americans were only a few generations removed from their own immigrant ancestors, they still maintained and promoted an identity that they were “real” Americans, as if this meant they had more worth and right to the promised land’s freedoms. Witnessing such blatant disregard for one’s own history and identity in order to justify a racist agenda struck me as the most un-American quality one could exhibit. Though, I’ve come to realize just how naïve that position truly is.

Even before obtaining my Irish citizenship, I struggled with my own American identity. While I am indeed an American by the truest sense of the word, that is only when comparing myself to those on the outside. When it came to other Americans who, like me, were born and raised in this country, I never fully felt completely connected with them; that I was somehow less American than them.

Much of this may have to do with the national makeup of my immediate family, such as my mother being English. However, I truly know that it was also influenced by recognizing the false promises and lies sold to many generations of immigrants, Native Americans, and black Americans.

When I discovered U2 for myself back in 2000, the United States and, by extension, the whole world, were unknowingly on the cusp of ending an era. The following year when radicalized terrorists flew airplanes into the World Trade Center, this event that served as the defining moment of my generation forcibly moved this country into a new period propagated by fear and hatred. It was during this time that I was starting to come of age.

Seeing the footage of the attacks and the subsequent wars over the years cemented in me, and many young Americans at that time, a sense of confusion and distrust in our leaders. Neighbors and friends of certain ethnicities or religions became targets for a seething, ravaging lust for blood that had laid dormant in white America for decades. As I was not completely old enough to understand the nuance of our cultural crisis and too old to ignore it, the only thing I could do was pay attention and learn.

I started the process to obtain my Irish citizenship as early as 2010. For a variety of reasons, it was a rather slow process and I didn’t get the final application sent to the General Consulate of Ireland until March 2016. During the following 11 months it took to get my citizenship confirmed, I actively engaged in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. I followed the news of the candidates’ campaign trails, watched primary numbers come in, and catch highlights from the debates. I voted in the primaries and even participated in come campaigning efforts in the weeks leading up to the election.

This election was the most important election I had witnessed in my lifetime. President Barack Obama had spent eight years fixing many mistakes made by the previous administration and, during that time, the opposition party was doing everything they could to sabotage his efforts. With Obama leaving the White House, victory was crucial.

During this time, I was open about my plans to get Irish citizenship. I talked to friends, family, and colleagues about everything. It was something that was very personal and exciting for me. Though I had taken steps to complete the application over the last few years, many of the conversations I had about the citizenship process were within the scope of the election. People made jokes that if Donald Trump were to get elected, then it would be my ticket out of America.

I saw the humor in those conversations, but acquiring Irish citizenship meant more than me than just an easy out. It was a representation of my identity shaped from blood ancestry and my own uneasiness with what America had become since 2001. I had always loved what I believed to be was America, but it was becoming clearer that the America I believed in was the false one. My dual citizenship was me reconciling with the existence of two Americas.

Growing up in an era of continuous conflict against religion, ethnicity, and ideology has shaped my being to be more sensitive to the needs of people deprived of the same opportunities that I have had. If being an American means I can deny for others what I demand for myself, then I do not want to be an American. Instead, I want to be in what America is supposed to represent.

I want to be in the America generations of Irish, and other nationalities, sought as a means of living a better life through their own will and determination. That is an inalienable right that everyone should be guaranteed to have. These are the lessons that I gained over the years of listening to U2, studying the message of The Joshua Tree, and connecting with my roots.

I don’t know what will happen in another 30 years. The world is moving at a much faster pace than it did in 1987 under a Reagan administration. We, as American citizens and citizens of a more globalized world, are living in uncertain and anxious times. Often, one feels almost powerless to change anything.

While U2’s cultural statement within The Joshua Tree was written in response to a world mired in a Cold War conflict, the message still rings true today as America continues to promote itself as the last bastion of freedom while taking rights away from those who would benefit most from that freedom.

However, if there is one thing I have learned from U2 over the years then it is that one must have hope, and to fight for what is right and just; not just for one, but for all. For what has become a broken promised land for many generations, the people still have the power to shape America into what people need it to be.

Next entry: Album Review: Smokey Robinson’s My World: The Definitive Collection

Previous entry: The Fourth Wall: I Am Not Your Negro