Now Playing

Current DJ: Alex Gilbert

Hologram Teen Hex These Rules from Marsangst EP (Happy Robots) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

by Bradley Morgan

by Bradley Morgan

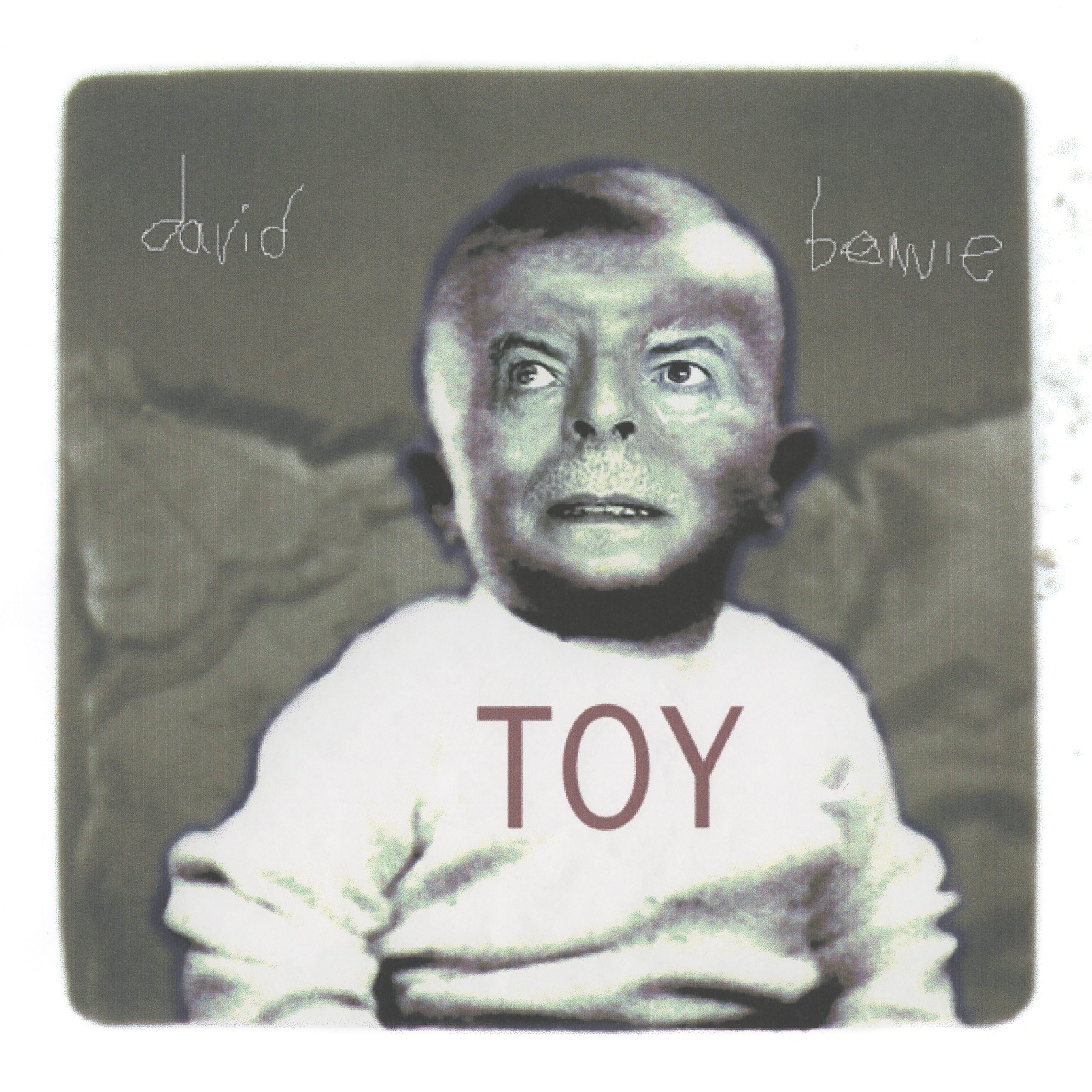

Bowie’s lost album finally arrives 20 years later

“I think the potential of what the internet is going to do to society, both good and bad, is unimaginable,” David Bowie told Jeremy Paxman of BBC Newsnight during an interview in 1999. “I think we’re actually on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.”

Bowie’s comments on the potentially chaotic intersection between the advent of the information superhighway and its relationship with and impact on society seem incredibly prescient, especially in hindsight with modern writers and critics often drawing parallels between Bowie’s future proclamations with critiques on modern ills such as the role social media has played within grander schemes to disrupt cultural and social institutions.

It’s a great quote from an excellent interview from the always eloquent Bowie, though only tending to resurface when navel-gazing about the past as we share it on our feeds collectively wondering where it all went wrong.

However, further into the interview and often excluded from clickbait articles, Bowie shares an idealistic fascination for what emerging technologies can do in the spirit of human connection. “From where I am, by virtue of the fact that I am a pop singer and writer, I embrace the idea there’s a new demystification process going on between the artist and the audience.”

Bowie shares a belief that in the 1990s, unlike previous eras within rock and pop music where decades were defined by cultural icons such as the Beatles in the ‘60s or Elvis in the ‘50s, no artist or group had emerged as a rebellious firebrand to symbolize the decade.

Instead, what defined the ‘90s for Bowie were subgroups and genres that emerged to create a more communal experience that could be reduced by the music industry into marketable terms and pushed along a conveyor of information, of which then the internet takes control because it can deliver more information in increasingly faster ways.

When challenged by Paxman whether the internet is really just another tool and delivery system, Bowie counters with “It’s an alien lifeform.”

Bowie, nearing the close of his fourth decade in the music business at the time of this interview, had always expressed a deep fascination with the impact of new technological advances on human connection and the artistic expression within, often stargazing to draw on what the cosmos can teach humanity about its limitless potential.

Here, at the dawn of a new millennium, was Bowie madly thrilled by what could be accomplished by art and an audience’s relationship with it.

By 1999, Bowie was coming to the close of an artistic renaissance he had experienced during the last decade. Prior to that, the 1980s had been the most commercially successful period of Bowie’s career, propelled by a string of wildly successful music videos on MTV in heavy rotation which featured hit singles where Bowie had carried further the New Romantic movement that had emerged as clones of his post-Berlin creative output.

Though selling wildly, Bowie’s creative output by the end of the ‘80s were panned by critics and creatively unfulfilling. Never one to stay behind the times or in one place too long, Bowie set out to provide a soundtrack to the new digital age of the ‘90s with a series of albums exploring drum and bass, electronica, jungle, techno, and industrial rock.

Closing out this new creative era for Bowie, and ushering in a new technological and cultural landscape he had set his sights on, was a project to usher in the Internet age, Toy.

The genesis of Toy emerged during the tour supporting Bowie’s 1999 album Hours, where he was regularly performing live songs that had been originally written and recorded during the 1960s. Bowie was very pleased with the energy of the live band reinterpreting these older songs and he felt this new sound captured a richness and maturity that was lacking in the original recordings.

So, following the tour, Bowie sought to capture the spirit of those performances by recording the band live in a studio and releasing the songs shortly after as part of a surprise album.

However, reality had not yet caught up with Bowie’s vision, and his plan for a surprise album release would ultimately be ahead of its time. Bowie’s label at the time, EMI/Virgin, was experiencing financial struggles and the rapid manufacturing and distribution of a surprise album during a time when CDs still dominated as a music medium proved to be too ambitious.

Even though Bowie’s entire back catalogue up to that point had become available for digital download in 2000 (another pioneering move for Bowie that illustrated his grasp of the Internet’s potential), his label expressed concerns that an album of re-recorded songs from four decades before would not prove commercially viable enough to resolve their financial woes.

Originally scheduled for release in March 2001, Toy was delayed and then eventually shelved. Bowie moved on, recording and releasing Heathen under his new label, Columbia Records, in 2002 with some original songs from the Toy sessions evolving into new form for that release.

Over the years, Toy had gradually gained notoriety as Bowie’s only lost album. This was certainly helped by Bowie who was adamant about finding a way to release the material because he felt so strongly about its quality, something echoed by those close to him who were involved with the recording process or had heard the material.

The earliest that recordings from Toy surfaced publicly were when rough mixes of the tracks were leaked onto the Internet in 2011, a full decade after the album’s originally planned release.

These mixes, none that were final master recordings, circulated in bootleg form for another decade until November 26th, 2021, when Toy was finally officially released as part of a new boxset spanning Bowie’s ‘90s electronica and industrial rock period, Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001), the latest installment of a boxset series chronologically documenting Bowie’s career.

Now, on the eve of the late popstar’s 75th birthday, Toy has finally made its debut as a singular work in the form of Toy:Box. Nearly 21 years after its intended release, Toy:Box offers listeners a celebratory glimpse into Bowie’s creative process and frame of mind at the dawn of a new technological age.

With material spanning three discs, Toy:Box is a comprehensive overview of Bowie pushing his imagination beyond the limits that technology and his record label forced upon him.

Disc one features the complete Toy album with all tracks mixed as final master recordings. Disc two features additional songs recorded during the sessions as well as alternate mixes of the final songs on Toy. Disc three features acoustic as well scaled-back electric renditions of the songs from the Toy sessions.

With 20 years of hype preceding it, Toy provides a fascinating listening experience. Less because of the fact its release comes on the heels of the 6th anniversary of its creator’s death, but more so because it captures a unique spirit and energy not captured in other albums from that part of Bowie’s career. The tragic element does not overshadow the quality of the album or the set’s supplemental material.

Toy represents Bowie at a crossroads in his life, something he was all too familiar with from his past. Within his various transitional periods, Bowie had always found a way to creatively purge a raw essence into something beautiful in order to move forward and progress as an artist and an individual.

While other personally evolutionary periods such as his Berlin-era albums are more well-known in the Bowie canon, the period of Toy represents something much different but still integral. While Toy does not feature groundbreaking songs that inspired new waves of bands and artistic rip-offs, Bowie was in a much different place at the turn of the millennium than in earlier decades.

Here was a Bowie that was more comfortable and secure with himself. He was sober, married, and had already achieved critical and commercial success. The future was both thrilling and alarming, but Bowie reconnecting with his earlier songs and finding new depth within them at a time when he didn’t have to prove anything to anyone was what was going to carry him forward.

And the future, for an artist that had seen the music industry change for four decades, was connecting with audiences in new ways. “The actual context and the state of content,” says Bowie to Paxman, “is going to be so different to anything we can really envisage at the moment, where the interplay between the user and the provider is going to be so simpatico that it is going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about.”

The story of Toy is one of being ahead of its time, which is a peculiar thing to say about an album updating decades old songs. Bowie’s plan to release Toy as a surprise album spoke to his ambitions of breaking new ground in how artists connected with an audience while navigating the earliest potential of what the internet had to offer. However, the music industry model at that time had been unable to catch up with Bowie’s grand vision and he could not afford to wait for it any longer.

Now that Toy is finally out, it is time to play it. Don’t become too glum at the idea of what its delayed release signifies now that its creator is no longer with us. Instead, listen closely to the life and joy emanating from it. Toy:Box beautifully captures a spirit and energy of a man so fascinated by a world of future possibilities, that he wanted to bring his whole self, even his past self, to embrace it.

Bradley's new book U2’s The Joshua Tree: Planting Roots in Mythic America has been published by Backbeat Books and is availalbe at a store near you.

Next entry: Vote for CHIRP Radio for the Chicago Reader Best of 2021!

Previous entry: CHIRP Radio Weekly Voyages (Jan 17 - Jan 23)