Now Playing

Current DJ: Liz Mason

Suki Waterhouse Big Love from Memoir of a Sparklemuffin (Sub Pop) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week, the discussion is about the theme of urban dystopia as portrayed in American movies. . This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

Kevin: "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here..." might as well have been posted at the entrances of America's big cities during the 1970s. Crime skyrocketed in metropolitan areas across the country during this era, and rampant arson famously turned New York City's Bronx into such a war zone that it even warranted an impromptu visit from President Jimmy Carter near the end of the decade. And of course, Hollywood capitalized on these fears by putting its own spin on the story of urban blight*. Who were we afraid of? And who would protect us?

Kevin: "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here..." might as well have been posted at the entrances of America's big cities during the 1970s. Crime skyrocketed in metropolitan areas across the country during this era, and rampant arson famously turned New York City's Bronx into such a war zone that it even warranted an impromptu visit from President Jimmy Carter near the end of the decade. And of course, Hollywood capitalized on these fears by putting its own spin on the story of urban blight*. Who were we afraid of? And who would protect us?

[Even without the threat of bodily harm, 1970s cinema does not paint New York City in a flattering light. The French Connection, Mean Streets, Taxi Driver... these films weren't exactly commissioned by the city's tourism bureau.]

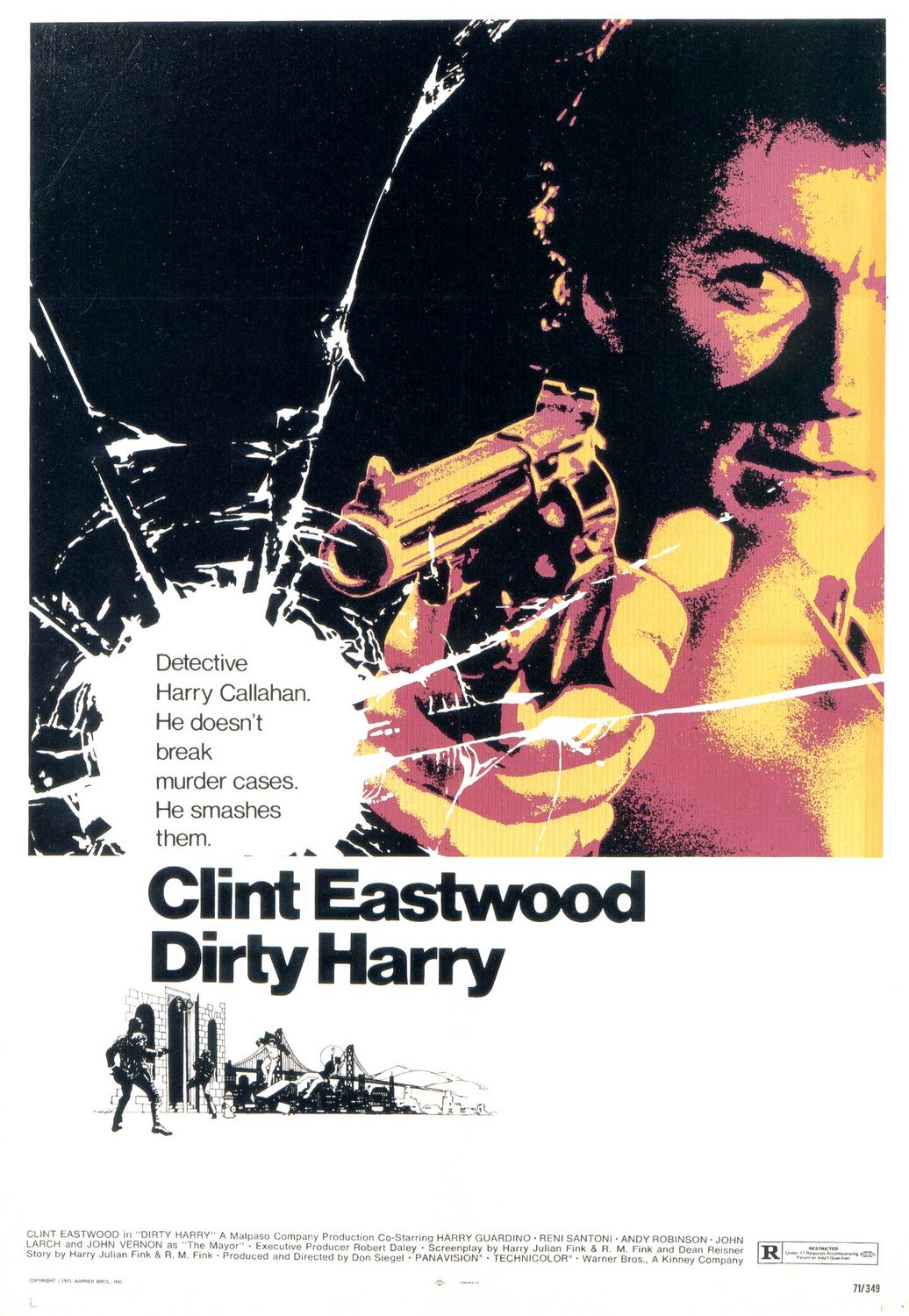

In 1970, the Clint Eastwood classic Dirty Harry introduced a cop (Eastwood's Harry Callahan) who was battling his own administration as much as the crooks on the street; those pesky rules and regulations were interfering with his ability to deliver frontier-style justice. By the time that Death Wish appeared four years later, the police had become virtually impotent and had seemingly surrendered the streets to gangs.

In Death Wish, liberal Paul Kersey (played by Charles Bronson in a career-redefining role) becomes a hardened, gun-toting vigilante after his family is brutally attacked by street thugs. Critics were horrified for what they saw as a promotion of antisocial behavior, but audiences ate it up... though unfortunately, that meant a long line of sequels which grew more bizarre with each iteration.

[Death Wish 3 is firmly in the "So Bad It's Good" camp -- even just the trailer is pure absurdist comedy. And for more madcap humor, check out the trailer for the cult film Class of 1984, about out-of-control high-schoolers. The "school beset by wild youth" theme has been a popular subgenre here -- stretching back from Blackboard Jungle in 1955 to Lean On Me, Dangerous Minds, and The Substitute in the '80s and '90s.]

With no abatement in sight by the end of the '70s, what did people envision coming down the pipe in the future? Enter John Carpenter's Escape From New York, where the America of the future decides to cede Manhattan entirely to criminals, and walls off the borough like a leper colony. The President's plane gets hijacked, crash-lands inside the prison, and it's up to one renegade (Kurt Russell's Snake Plissken) to get him out. Fantastic premise, though the finished product will probably come off as a bit sluggish and more than a little dated today. (Clarence, I know we disagree on this!) Nevertheless, it was a brilliant reflection of the zeitgeist of the time. What do we do about crime?

* Clarence, what urban crime films do you think were the most powerful of that era? (Did you know they were remaking Death Wish with Bruce Willis?) Note that I haven't even gotten around to the inner-city gang films of the early '90s! How relevant is the theme today? Despite all the attention on Chicago and gun violence in recent years, Spike Lee's Chiraq seemed to draw scant attention -- though this might have much to do with the offbeat style of the film.

* What do you feel about the connection between films like Death Wish and events like the Bernie Goetz subway shooting in 1984?

* In many of these tales, the unspoken elephant in the room is race. Studios were fearful of how it might look to have police/gangs broken down by racial lines, so audiences were treated to an assortment of multi-racial gangs in everything from the aforementioned Death Wish 3 to another Carpenter film, Assault on Precinct 13. About the former, Roger Ebert wrote, "One of the hypocrisies practiced by the Death Wish movies is that they ignore racial tension in big cities... I guess it's supposed to be heartwarming to see whites, blacks and Latinos working side by side to rape, pillage and murder." Your thoughts?

* Something that struck me was how today's dark superhero tales -- especially those involving Batman and Gotham City -- might be harkening back to those days of "concrete jungles?" Today's cities are largely safer than ever (certain parts of Chicago notwithstanding), even as police-related tension is on the upswing. We could also riff on the depiction of the big-city policeman as well? Let's hope the reality is better than what we saw in Bad Lieutenant.

Clarence: To this day, I didn't get and still don't get the appeal of Bad Lieutenant. The main character and premise are just so one-note: "OK, in this scene you are the most repellent cop and human being imaginable. And in every other scene, too." The punishingly heavy-handed religious symbolism doesn't help. I like Harvey Keitel, but this film doesn't ask for much as far as acting range.

All I remember about Chiraq is the ridiculous "controversy" about the name. More people in City Hall got worked up over a movie title than the continuing bloodshed on the South and West sides. From what I've read, the movie itself isn't one of Lee's better efforts, but it is interesting how touchy prominent people get about depictions of this subject.

I've never seen Dirty Harry or Death Wish in their entirety, but I've seen references to them so often I feel like I'm familiar with their central themes. My main '70s dystopic touchstones are Taxi Driver and The French Connection. Taxi Driver is sobering journey through the mind of someone at the end of their rope who has the knowledge and skill set to do something about it. The fact that Travis Bickle is a war veteran is an important angle, as it is with other Hollywood protagonists who navigate the world through that point of view.

The meaning and/or message of The French Connection comes down to a question: What if Popeye Doyle just let the heroin dealers go rather than rampaging through the city trying to find and arrest them? Several civilians and law enforcement officials wouldn't be in the hospital and morgue, I'm guessing. In the confines of that movie, the police are far more dangerous to the general public than the criminals they're chasing. I have no idea if William Friedkin meant this as a critique, but that movie is a great example of the dangers of obsessive, unchecked power in the wrong hands; in this case, the hands of someone with a badge and a gun.

The entire premise of Batman also takes a negative view of the police, but in a different way. I would hate to be a resident of Gotham City, a place where crime is so out of control and the police so impotent they have to rely on a borderline-psychopathic billionaire vigilante to save them from criminals over and over again. To me, this is the worst kind of dystopia, one with no real hope of getting any better, where your fate is tied not to the community but a single self-appointed protector.

As for non-fantasy dystopias, you have to look at what was going on historically and economically in the Big City in the '70s: recession, school busing, layoffs, mounting urban violence, protests of one kind or another, etc. Since we live in a country that thrives on violence and anxiety there's always an audience of aggrieved but otherwise well-off people who want to see their frustrations and fears acted out. I think what you point out about race is central to this kind of movie, especially considering that in the big films it's usually a cis white male who's pulling the vigilante trigger. (The blaxsploitation genre was an outlet for African-Americans do to their thing, but there were very different political and social contexts.)

Ultimately, I feel these films are not so much about THE world is falling apart as a specific person's world, a world where things like security and traditions are being ignored, taken away, or replaced by something else. The ultimate example of this is the Michael Douglas thriller/satire Falling Down, where the main character is so fed up by a string of incidents that he feels justified in gearing up and "making things right" all over anyone he decides is in need of that treatment.

A certain national organization loves to talk about how "the only cure for a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun." But who gets to decide who the "good guy" and "bad guy" are? We touched on this very briefly in our talk about Hell or High Water. There was a question you asked and I not-so-artfully dodged, but I have to bring it up again - in the context of story-telling, is this kind of behavior ever justified?

Also, this subject has got me thinking of movies based in the opposite of urban dystopias - the quiet, safe and economically well-off urban (usually suburban) enclaves where characters still manage to inflict physical and emotional violence on themselves and others. I'm thinking of movies like The War of the Roses, Kids, and American Beauty. Do you think there might be some kind of connection between these two genres?

Kevin: Clarence, you're asking if using guns to fight bad guys is ever justified? Well, I'll quote Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid: "Fighting always last solution to any problem." But sometimes, the other possible solutions evaporate pretty quickly. If help's not around and violence is knocking at your door, what then? (Did anyone not cheer when Miyagi fought off the hoodlums who were attacking Daniel-san in that film?) I think what storytelling does is humanize the danger and fear, and lets us walk for a bit in someone else's shoes. Those of us who live in safe and secure neighborhoods... well, I don't know if we're the ones who should be giving suggestions to those in crime-ridden areas about how to protect themselves.

Interesting point about the emotional violence that families are subjected to in affluent enclaves, and I'd also add Ordinary People to that list as well. With American Beauty, though, I think Lester's wife is a bit of collateral damage? He's declared war on his entire way of life, and she gets caught in the crossfire when she refuses to come along for the ride. In AB, there's also a Walter Mitty vibe -- lives of quiet desperation, to be sure.

With The French Connection (and Dirty Harry), you hit upon the point of unchecked police power. There's a scene from Training Day, where Det. Alonzo Harris (Denzel Washington) spells it out: "It takes a wolf to catch a wolf." We eventually learn that Harris is repulsive in all sorts of ways... but is he necessarily wrong here? Of course, it's a slippery slope from Harris to the judge/jury/excutioners like Judge Dredd and Robocop*, and we've experienced the painful lessons of what happens to law enforcement without proper oversight.

[* The original RoboCop, directed by Paul Verhoeven, is a brilliant, scathing pseudo-satire re: police, the military-industrial complex, and corporatism. And when it came to urban dystopia, how 'bout "Old Detroit?"]

With regards to race -- I briefly touched upon the spat of inner-city gang movies we began to see in the early '90s, with Boyz n the Hood and Menace II Society, among others. I've often thought that a film like Boyz represents a conundrum. On one hand, it's a powerful film that raises all sorts of important questions (gentrification, police brutality, violence begetting violence), and yet, I also can't help but wonder if, to white America, it also subconsciously reinforces all sorts of negative stereotypes. Inner cities = black = danger. A few years ago, I interviewed Maurice Berger, author of the book/exhibit For All the World To See, about visual media and the civil-rights era, and what he said was that the problem wasn't displaying the world of Boyz n the Hood. The problem was that this world was all that most filmgoers were exposed to re: black communities. We don't see the range of characters portrayed in films like the aforementioned American Beauty.

I'm glad you mentioned Falling Down. That film became part of the political zeitgeist of the early '90s, having been released a year before 1994 -- the era of the "Angry White Male," characterized by the GOP landslide in congressional races that fall. It's a mashup of a tale, divided between the adventures of "D-Fens" (Michael Douglas), and the hapless detective (Robert Duvall) assigned to track him down. The former is by far the more interesting half, as D-Fens cuts a swath through a certain sort of urban dystopia*... just not (outside of a couple of Latino toughs encountered early on) an overtly-threatening one.

[* Being gouged at a convenience store, missing the breakfast cutoff at a fast-food restaurant, getting hassled while walking through a golf course -- these all seem like minor grievances to yours truly, but apparently the frustration had been building within D-Fens for quite some time...]

Let's turn our attention now to the present. Superhero cinema aside, what's the depiction of big cities been like in today's Hollywood? Where are we headed? Any notable films come to mind? Precious? Does Nightcraw

Clarence: When I think about that question, I have to consider the current lineups on TV. It's weird how much play Chicago gets in procedural dramas that aren't Law & Order, like Chicago Med, Chicago Fire, Chicago PD, Chicago Justice, etc. I think this reflects the schizophrenic perception America has about our city, and big cities in general. On a per capita basis, when it comes to murder and mayhem, you are safer living in Chicago (or New York, or Los Angeles) than, say, New Orleans or Gary, IN. But those places aren't The Big Bad City, and mainstream media depends on ideas that are, well, mainstream.

The media coverage about crime that Chicago is experiencing in the '00s and '10s is no different that what New York received in the '70s and LA got in the '80s and '90s. [Thanks to the internet and a 24-hour news cycle, there's arguably more coverage of Chicago.] The more I think about it, the more I feel that the segment of society that is justified in expressing a dystopic vision of America are the families of the people who have been killed by police officers, too many due to excessive or unnecessary force. These officers have lived in a world where Dirty Harry and Rambo are held up as the way to fix problems, and innocent people have paid the price. For the rest of us, this is all about theory and media tastes. But a significant number our our fellow citizens are living it for real.

I have not seen Nightcrawler, Precious, or Elysium - they are all stuck in my movie queue (which I've promised myself to spend the rest of this year getting through). The premise of Elyisum did intrigue me. In a way, it's similar to films that go all the way back to The Great Gatsby, where the basic premise involves the rich having separated themselves from everyone else. This is a theme that I feel is hard-wired into American culture, and has recently curdled into a political position thanks to people like Ayn Rand, who got a lot of mileage out of it with novels (e.g. The Fountainhead) that have yet to translate successfully onto the big screen. I think if someone tried to either adapt another Rand tale or remake Falling Down, it couldn't help but become political, with the Fox News crowd gathering on one end, and a sizable opposition on the other who would find these projects pretty dated.

From what I do know about them, films like Nightcrawler and Precious

[Want to add to the conversation? Leave a comment below!]

Next entry: @CHIRPRADIO (Week of May 22)

Previous entry: @CHIRPRADIO (Week of May 15)