Now Playing

Current DJ: DJ M-Dash

The Donnas Who Invited You from Spend The Night (Atlantic) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

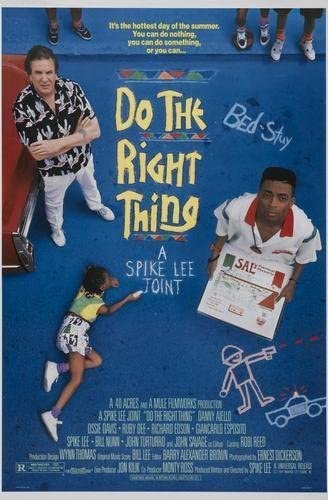

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the Spike Lee classic film Do the Right Thing (1989)

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

Kevin:

"My people. My people. What can I say? Say what I can. I saw it but I didn't believe it. I didn't believe what I saw. Are we gonna live together? Together, are we gonna live?"

Those are the closing words of Mister Señor Love Daddy (Samuel L. Jackson), radio DJ and pseudo-narrator of Do the Right Thing -- Spike Lee's third feature film and the one that catapulted him to national prominence in 1989.

Do the Right Thing garnered Academy Award nominations for Lee (Best Original Screenplay) and Danny Aiello (Best Supporting Actor), though Lee felt particularly slighted at the Oscars next year. And understandably so: “When Driving Miss Motherf—-ing Daisy won Best Picture, that hurt." However, as he added years later, "no one’s talking about Driving Miss Daisy now.”

Do the Right Thing takes place over the course of an entire summer day -- the hottest day of the year, in fact -- in Brooklyn's Bed-Stuy neighborhood. Much of the film centers around local institution Sal's Famous Pizzeria, owned and operated by Sal (Aiello) and his two sons (John Turturro and Richard Edson), who are three of the very few non-black faces in the community.

While Sal takes pride in the fact that he's been a fixture in the area for decades, his sons are much less enthused. Ditto for delivery man Mookie (played by Lee himself), who often walks a tightrope between young militant rabble-rousers like Buggin' Out (Giancarlo Esposito) and Turtorro's Pino, the latter of whom harbors less-than-kind attitudes towards their black customers*.

[*Of course, as Mookie points out, Pino's favorite celebrities are all black. Just not "truly" black, in Pino's eyes.]

Despite Buggin' Out's disdain for white America at large, he's a regular customer at the pizzeria, until he notices that Sal's "Wall of Fame" (photos of famous Italian-Americans like Al Pacino and Joe DiMaggio) doesn't have any black faces. And that sets him off.

While his attempted boycott of Sal's Finest picks up little traction, it starts the ball rolling towards a tumultuous final act that climaxes in a wild brawl that spills out of the restaurant. When police arrive to break it up, the cops wind up killing one of the black combatants (Radio Raheem, who harbored a grudge against Sal over the volume of his namesake). They then speed off... leaving Sal and his sons to deal with the angry mob of locals who have gathered at their storefront.

It's a challenge to distill Do the Right Thing down to a few paragraphs, because there's so much at work here. I've only scratched the surface with regards to characters -- this story is full of amazing supporting players, such as the three local gadflies who provide a running commentary about the community (one of whom is played by Frankie Faison, better known as Baltimore Police Commissioner Burrell in The Wire).

And there are brilliant moments of comedy, usually incited by culture clashes. My two favorites? Radio Raheem's request for "20 D Energizers" from the newly-opened Korean grocery, and the hubbub that starts when a white bicyclist (in a Larry Bird T-shirt, no less) accidentally bumps into Buggin' Out and scuffs up his sneakers.

Other notes:

* I'd strongly recommend that folks dig into the background of how the film was made. For one thing, since Lee wanted to film in Brooklyn, he had to use unionized film crews which had very few minorities. But Lee was able to successfully negotiate for the inclusion of black film production workers, some of whom were eventually able to join the union.

* The one element that didn't work for me? Spike Lee's Mookie. I don't think it's a shocker that Lee largely stepped away from acting as his career evolved. Supremely talented as a director and cultural commentator, but much less so as an on-camera emoter.

* Spike has said that studio executives were quite uneasy with the film and its ambiguous ending. There was a fear that the movie would incite black audiences to riot, which was a line of thinking that re-appeared a few years later during the release of Malcolm X (also a Lee film). Of course, it was ludicrous to ask Lee to "solve" the issue of race in America... and he said as much.

* The issue of gentrification was touched on briefly in the film, but Spike has had much more to say about it in recent years. As of 2016, Bed-Stuy was down to 49% black... and up to 27% white.

Questions for you, Clarence! I have many questions. Regrettably, however, I have no Sal's Famous Pizza to share. (Um, can anyone point me in the direction of a slice, please? Extra cheese? I'll fork over the additional 50 cents.)

-- The ending. Have you read about what Lee has said in recent years about the climax of the story? (That Mookie did not throw that trash can through Sal's window to redirect the crowd's violence towards the restaurant instead of the family.) How did you read that situation? Watching it for the first time years ago, I interpreted it as Mookie joining along with the mob... but then on a later rewatch, I believed he was looking to defuse the situation in his own way. Now, after Spike's recent words, I don't know what to think.

[Spike has said that no black viewer has ever asked him why Mookie threw that trash can. Interesting.]

-- The whole spat over Sal's Wall of Fame -- your thoughts? I dunno, Clarence, I think it's a great metaphor for our nation's problems in a lot of ways. When Buggin' Out approaches Jade (Mookie's sister, and played by Spike's real-life sister Joie Lee) and asks her to join his boycott, she replies, "What good is that going to do? I'm down with doing something positive in the community."

-- Since we do volunteer for a music station, what did you think about the role of music in the film? Public Enemy's "Fight the Power" was blasted on Radio Raheem's boombox non-stop -- to the point where even the rest of the block got tired of it. ("Can't you play anything else?" "I don't like anything else!") Did you also notice how the Latinos in the film were also closely identified by their salsa?

This is a broader question, perhaps, but what is it about music and identity where many of us (white, black, Latin, and everyone in between) need to shout our preferences from the rooftops, so to speak?

-- Where does Do the Right Thing rank among your favorite films about race? (And what other notable films would you list?) How about within Spike Lee's oeuvre?

[In lieu of pizza, I'd also happily accept a chicken parm, like the one Mookie delivered to Mister Señor Love Daddy...]

Clarence:

Mmmmm...I would not turn down a chicken parm right about now!

I first saw Do the Right Thing when movies were becoming a thing for me. Its importance to how I understand what movies can do cannot be understated. [I would also recommend his first major release She’s Gotta Have It, his other summer-in-the-city movie Summer of Sam, and also 25th Hour, a quiet and graceful post-9/11 elegy for New York City and the good-time 1990s.]

Do the Right Thing touches on so many themes that are just now being put front and center in America’s Conversation About Race®. A convo where, then as now, not all of us African Americans have the same opinions about things, Jade’s response to Buggin’ Out being one example.

Even though it was made 31 years ago, this movie is 2020 in microcosm; A black man is killed for no reason by the cops (using a chokehold, no less) and the question is what should be done about it. I’ve always thought that Mookie was participating in the crowd’s reaction, not trying to deflect from it.

Is that “good” or “bad?” That is the question, isn’t it? Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once said “A riot is the language of the unheard." [not one of his more popular quotes]. He then asked "What is it that America has failed to hear?”

Certainly not the music coming from black creative minds. If I may rhapsodize for a moment, music is the language of the soul. It’s a direct line to our emotional states, it’s a connection to our individual and shared history.

Most of the people who’ve bought rap records from Public Enemy et. al. since the invention of the genre are white. That might be one reason in 2020 the crowds protesting George Floyd’s murder are so diverse. The frustration and pain of black people are a fundamental part of American music. To not have your outlook changed by it may say more about you than anything else.

Unless, of course, you're a racist or a corporation trying to make some money. I do remember the general fear of riot when Malcom X went wide. And Boyz N the Hood. And Menace II Society. And Django Unchained. And Straight Outta Compton. And Chi-Raq (one of Lee’s recent films). Ever since Shaft helped kick off the Blaxploitaton era, theaters are always worried that movies of a certain type with a black cast are going to cause trouble. Even a harmless movie like Black Panther got idiots on the right talking about plots and conspiracies about revolution.

It goes the other way, too. When it comes to Hollywood’s fantasy of peaceful racial reconciliation, we still are talking about Driving Miss Daisy, only now it’s called Green Book. It is hard to get a mainstream film about race made that doesn’t end up drowning in phony sentimentality and quick and easy answers.

That’s one reason this movie is so important, in my opinion. The only other fictional movie about race I can think of that I like is In the Heat of the Night (1967), starring Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger, which showed all the ugliness of day-to-day racism without pandering or false happy endings. The other race-based films I hold in regard tend to be documentaries (13th, I Am Not Your Negro).

Maybe it goes without saying that bigotry is a tough sell in the entertainment industry. Kevin, Has a movie (or a group of movies) ever changed your mind about how you see a group of people, whether ethnic, religious, or social? Also, I noticed Gone With the Wind is being pulled from streaming services. Should it get the same treatment as Birth of a Nation?

And also, what if anything should the film industry do right now to be part of the solution to the questions that are (again) being put front and center in our country?

Kevin:

* Before I jump into more general thoughts, I've got one more serious question about Do the Right Thing.

Let's look at that final brawl again. Radio Raheem enters Sal's Pizzeria, with his boombox blaring, and furious because Sal had told him to turn his music off in the restaurant earlier that day. When Raheem practically dares Sal to smash his radio to bits, Sal obliges. Raheem then drags Sal over the counter, and it wouldn't be a stretch to presume that he could've choked Sal to death if the police hadn't intervened.

Suppose at that moment, one of Sal's sons shoots Raheem to save his father. Certainly believable, right? Raheem dies. Same outcome. What then? Would Raheem have gotten what was coming to him in that scenario?

* The general consensus about the power of mass media is that it's easier for cinema to help people form opinions from scratch than to change them. Once we've cemented views about anything (especially based on personal experience), it takes quite a bit to pry them loose. When I taught at Loyola, my students at the time mentioned Blood Diamond as a film that had a significant impact on their thinking, largely because they had been entirely ignorant about the diamond trade.

In that spirit, I'm going to list a trio of wonderful films about Muslim women in the Middle East that had a great impact on me: Ava, Mustang, and Wadjda. All three were written and directed by females, and in the case of Wadjda, it was not only the first feature film directed by a Saudi woman, but also the first feature shot entirely in Saudi Arabia.

Each story involved three degrees of separation from my own upbringing (religion, gender, local culture) -- and we can throw in a fourth layer of disconnect from my current status, since almost all the main female characters were teenagers.

* I completely agree about the pandering and "false happy endings" that we often get from Hollywood concerning race. This is actually one of the reasons why I was disappointed with the final act of Jordan Peele's Get Out -- he went for a neat, feel-good conclusion in a final scene that involved a last-minute rescue by law enforcement.

Since you mentioned In the Heat of the Night, do you have any thoughts about the depiction of black cops on screen? When you mentioned chokeholds, I couldn't help but think of Denzel Washington's Alonzo Harris in Training Day, who, after watching young protege Jake Hoyt (Ethan Hawke) use an illegal chokehold in a fight against two crackheads, tells him later, approvingly: "It takes a wolf to catch a wolf...You did what you had to do, right? You did what you had to do."

[Not that Alonzo is ultimately the depiction of a "good" cop, but... we're rooting for these guys when evildoers are punished, right? Even when they bend the rules? It's the Dirty Harry phenomenon.]

Did you ever catch American History X, with Edward Norton? Not a perfect film, but a mighty interesting tale involving a former skinhead (Norton) who, after being released from prison, seeks to prevent his younger brother from traveling down his same path. In flashbacks, however, you see exactly how the Neo-Nazi movement grew appealing.

Along the way, there's also a basketball game where blacks and whites (Norton's skinhead crew) are playing for claim of the neighborhood courts, and... uh, are we encouraged to cheer Norton's victory? The music and editing sure makes it seem that way, right? And ultimately, there was no simple racial reconciliation here at the conclusion of the film.

Here's an even more subversive piece of cinema -- CSA: Confederate States of America. Directed by Kevin Wilmott (and "presented" by Spike Lee), CSA is a retelling of the last 150 years of American history... except that in this timeline, the South won the Civil War. Harriet Tubman is captured, Abe Lincoln is exiled to Canada, and things get even worse from there. Uncomfortably straddles the line between satire and drama at various points, and is a rather original look at our country's racial timeline.

* Re: Gone With the Wind -- did you see the recent comments from BET founder Robert Johnson on the topic? If the black community -- and not just the activists -- truly finds it offensive, then I'd be on board with giving it the Birth of a Nation treatment. Johnson doesn't seem to think it cares much one way or the other.

I also think back to this interview with Spike Lee, where he labels Tyler Perry shows "Coonery Buffoonery." How many young folks today have seen Tyler Perry vs. Gone With the Wind? And what about the power of imagery within hip-hop videos? Migos' "Bad and Boujee" has almost a billion views. This is popular culture, and it's not coming from white studio moguls.

* The big enchilada here -- what can Hollywood do to be part of the solution? I can tell you what was guaranteed to not win hearts & minds: the "I Take Responsibility" PSA, full of white celebrities professing guilt over their perceived contributions to the state of current race relations in America. (Did you manage to make it through the whole thing? I couldn't.)

We also don't need more films espousing feel-good solutions to racial strife, as you mentioned with Green Book. We don't even necessarily need more films about capital-R Race, though I'm all for them, if done intelligently. We simply need more minority voices, period.

Let's see more films from the perspective of the Vietnamese immigrant. The Indian immigrant¹. The African immigrant. (I'm extremely curious about the interaction between African immigrants and the native black community as a whole.) We're starting to see more women behind the camera, which is fantastic, and we could certainly use more.

The more tales we have about the American experience, from all walks of life, the more we'll be cognizant of our shared culture. Without a shared collective national culture, how much of a country are we?

[¹I loved Meet the Patels, from 2014. Terrific window into the Indian-American community.]

But we also shouldn't put all this on Hollywood; we as consumers have a responsibility to seek out these stories as well. As Spike Lee added in that interview about the late director John Singleton, people came out for a gang movie like Boyz n the Hood, but when Singleton did Rosewood, "Nobody showed up. So a lot of this is on us." In the old days, you were limited to what was playing at your local theater, or carried at your neighborhood video store. No longer.

I'll close with one final thought. Think back to some of the most interesting films you've seen -- weren't they unafraid about ruffling some feathers? Do the Right Thing was one of those films for me. A Clockwork Orange. The Last Temptation of Christ. Typically, Hollywood has been a tool of the Left to push back against what some viewed as the stodgy morals of the Right.

Has the pendulum currently swung the other way? Is the Left now the side that's scared of frank discussions about culturally-sensitive topics? Look at the vitriol that was launched at Planet of the Humans, a recent Michael-Moore-produced documentary that countered some of the claims of renewable-energy advocates. Moore is the furthest thing from a conservative voice, but it mattered not -- he was swallowed up by the Left, and the film was pulled from YouTube.

Just this week, Matt Taibbi put forth the argument for how "The Left is Now the Right" in a rather thought-provoking essay. Black Lives Matter is everywhere now -- perhaps most folks still simply view it as a slogan, but it's also a political organization with aims that go beyond anti-police brutality... and the organization should be fair game for critiques, whether in film or elsewhere. Are we going to be afraid to make those critiques?

Clarence:

I want to spend some time on that first scenario you describe, Kevin, and I want to be careful how I write my response because while I’m not a lawyer, I am a citizen of the United States and I want to make sure my admittedly biased point of view is as clear as I can make it.

Suppose the scenario you described played out. Can you prove in a court of law that Raheem had intent to kill Sal? I suppose either way you could argue negligence on Raheem’s part - but would that justify killing Raheem being killed by someone else in response?

Your scenario is roughly what happened to George Floyd. A police officer had some kind of exchange with Floyd, and it escalated to the point where the cop felt it appropriate to put his knee on Floyd's neck, which led to his death. There’s no way to prove what the policeman was thinking, so let’s leave intent out of it for now.

Suppose one of Floyd’s relatives, seeing what was happening to him in the moment, pulled out a gun and shot the officer to death. Would that officer have “gotten what was coming to him?” I would submit that, in both of our imaginary scenarios, it really depends on your point of view.

And this one of the central themes of the Civil Rights movement - EQUALITY under the law. The fact is, how someone who uses deadly force in these scenarios would be treated in this country’s legal system very much depends on that person’s race, both in courts of law and public opinion.

[And to be clear, I feel that the officer, even if he didn’t intend to kill Floyd, should have known that what he was doing in that specific instance would lead to Floyd’s death, which makes his actions murder.]

Remember, it wasn’t too long ago that if someone like Raheem had so much as talked back to a white person the way he did, that would have been justification for killing him.

I also saw the alternate ending of Get Out, and I think that ending would have been much closer to the truth about the real world we live in. Fixing these kinds of fundamental imbalances is what the Civil Rights movement is about.

As far as depictions of black cops on screen, I have to say I don’t feel there are a lot of overarching themes I see across movies. For example, this week I watched Dolamite, the Blaxploitation classic where the black cop ultimately and gladly helps the protagonist get revenge on his criminal and police enemies, and I’m currently watching the reboot of Perry Mason, where a black police officer only reluctantly assists the protagonist in unraveling the case at hand.

I would say there’s plenty to dig into when considering cops in general and their archetypal roles in movies and TV. The good folks over at The Take did a very good video essay on this, showing that how police are depicted on screen has been heavily influenced by real police departments.

Of course, any movie or TV project has a lot of people involved in making it happen. [Weren’t the showrunners behind Game of Thrones supposed to be developing a project similar to that CSA film you mentioned? I imagine that project might be on hold for now.] The major media distribution channels are still dominated by white executives, and/or black Executives who are not keen on “rocking the boat” when it comes to showcasing truly revolutionary points of view.

The good news is that this is changing somewhat, and thankfully moving beyond the clumsy, tone-deaf “I Take Responsibility” spots you mentioned. I agree with you, the less said about those, the better.

You asked if we’ll be afraid to critique the Black Lives Matter movement. I think that’s a fair question that would be easier to address if any of the current rumors and allegations made about the organization were actually proven to be true. In terms of conspiracy-talk, Black Lives Matter is undergoing the same scrutiny as groups such as Rainbow/PUSH (formed in the 1970s), the Black Panthers (1960s), and even the NAACP (by far the least “radical” of these movements).

Contrast this with organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and their documented 100+ year history of violence and murder in America, and the recent Boogaloo movement whose members are openly campaigning for a race war, something I have yet to hear anyone from Black Lives Matter officially advocate.

It’s interesting how when a group of white people get together to publicly advocate for their interests, it’s a political movement. But when black people do it, it’s assumed at the start to be some kind of Plot Against America®. Again...EQUALITY is missing from this perceptual equation.

I think an important question in this regard is: What exactly should we be afraid of when groups like BLM stop asking for and start demanding change? To be able to articulate honest answers to that would be another step in the Conversation About Race® that will give us all an idea about where this country is headed.

Did you see the movie? Want to add to the conversation? Leave a comment below!

Next entry: Critical Rotation: “Miles” by Blu & Exile

Previous entry: Critical Rotation: “To Know Without Knowing” by Mulatu Astatke & Black Jesus Experience