Now Playing

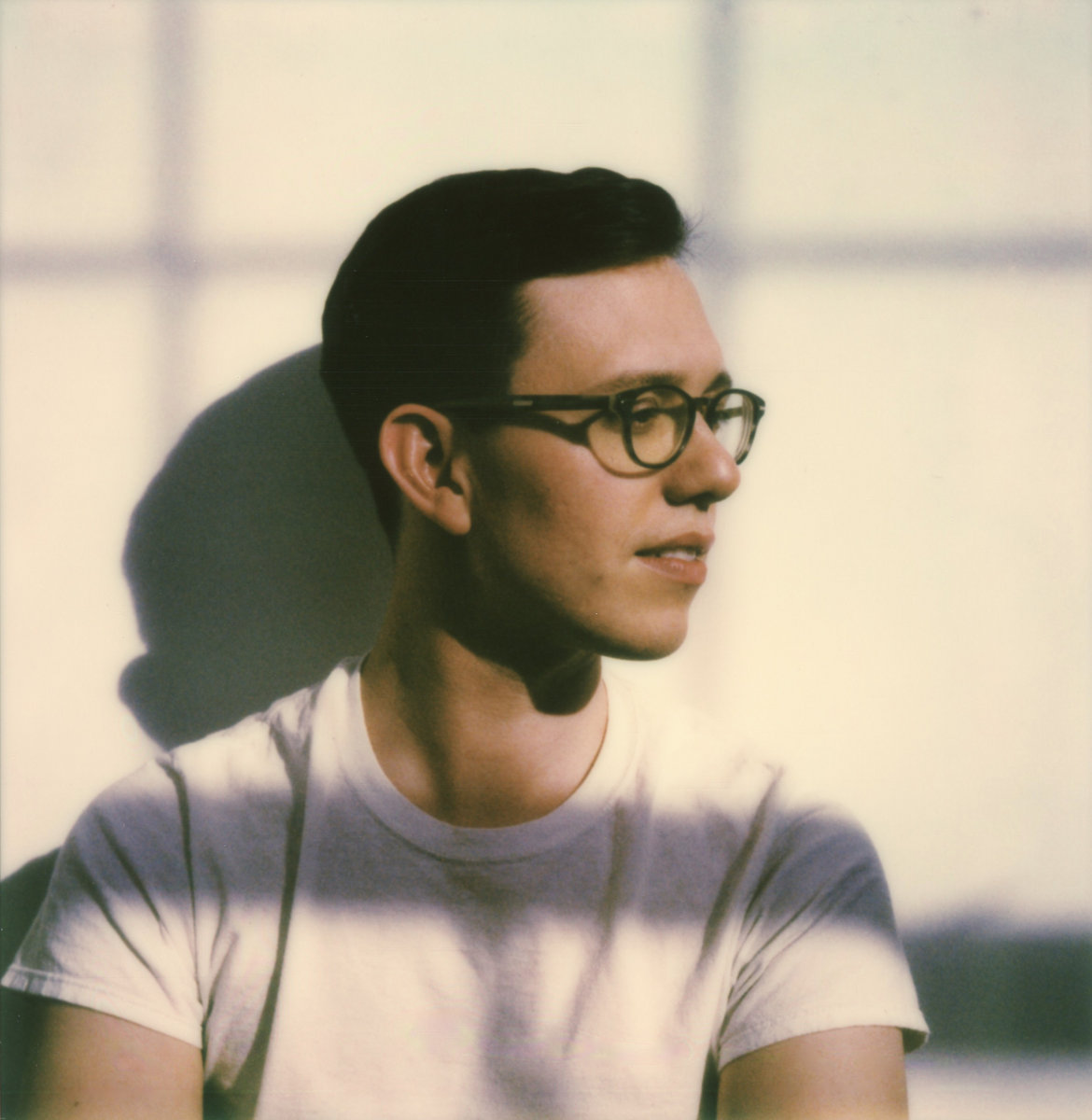

Current DJ: Alex Gilbert

Baby Berserk Entertainment from Slightly Hysterical Girls With Pearls (Bongo Joe) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

by CHIRP Radio DJ and Features Co-Director Mick R (Listen to his most recent shows / Read his blog)

DPCD is the name of a sonorous, soft, and elegant folk project that graciously calls Chicago home. The group is lead by Alec Watson, who fills the song’s lyrics with ruminations on connection, compassion, and salvation.

Drawing on his past in the Evangelical Church he has a unique and thoughtful approach to the world, its problems, and the ways that we relate to each other as human beings.

Most striking of all though, is his tenderness of presentation, which can’t help but remind one of Sufjan Stevens, or even Conor Oberst, at his most vulnerable.

Alec and his bandmates will be releasing their debut on October 1, an album conspicuously titled It's Hard for a Rich Man to Enter the Kingdom of God. The album is not shy or penitent about its appeals to spiritualism and mysticism, and neither is Alec himself.

As you will no doubt be able to tell, he’s given his faith a great deal of thought over the years, and at this point in his inquisitive journey, we find him more devoted than ever.

He may not love everything about his past, but understanding how he can transpose what was good about it into a better future for him and others is part of what motivates the project as a whole.

I was able to catch up with Alec to talk about his band and their new record over email. His responses were enlightening and thoughtful in ways that often caught me off guard. You can read his earnest responses to my inquiries below:

Purchase It's Hard for a Rich Man to Enter the Kingdom of God

[The following interview was conducted via email on September 24, 2021. The responses been edited only slightly for the sake of clarity.]

Please introduce yourself to our audience and tell us a little about yourself.

Hello CHIRP readers! My name is Alec, my music is called DPCD. I live in Chicago. I make this music with my friends Samantha Connour, Ethan Parcell, Jesse Bielenberg, and Kenan Serenbetz.

What does DPCD stand for?

DPCD is a four-letter acronym I found in the back of my great-grandfather’s bible. He was an Indiana Quaker. I was doing an archiving project where I was copying and making notes of all of the places he interacted with the text — underlining, writing in margins, etc.

When I got to the very end where there are always a few blank pages, DPCD was written twice in a square. I don’t know what it stands for! Any guesses?

Tell us a little about the meaning behind the title of your new album It's Hard for a Rich Man to Enter the Kingdom of God, and the themes you explore on it.

The title is something Jesus says after a conversation with a rich man. The man is asking what he has to do to inherit eternal life. Jesus says "follow the commandments." The man says "I already follow them." Jesus says "Ok, then give away all of your wealth and follow me." The man gets sad and walks away. Jesus says “It’s hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.”

Christian scripture is often employed in short, contextless bursts. Sometimes the feeling is warm and fuzzy — “Love is patient, love is kind.” Sometimes what is communicated is doomy and gloomy, like a billboard with clip art flames that says “Repent! For the kingdom of heaven is at hand!”

I wanted to use this trope, the contextless scripture quote, but with a verse that I’ve never seen used like that before. I wanted to aim these words at the powerful in a way that they aren’t usually aimed.

I’ve noticed that a lot of people my age who grew up in the evangelical church have embraced left politics. I think this is partly because of the radical nature of evangelicalism. As evangelicals, we were taught to "live radically for Jesus," to give our lives to the cause, to save the world essentially.

We were also taught to critique "secular materialist culture," -- shopping malls, advertisements, consumption. But this critique never went as far as looking at capitalism, which I think has to do with the Church’s alignment with Cold-War era conservative politics.

And the Church is still deeply invested in maintaining the status quo. Much of that radical energy is used for causes that are harmful — repression of Queer gender identity and sexuality, fear-based evangelization, and unhealthy ego suppression.

But leaving these things behind, I think a desire to follow a large, world-saving project remains in many former evangelicals. And there are actual problems our world needs help with right now! Let's redirect our radical energy!

The last thing I’ll say is the most personal. Everything I've said so far I believe in and is very important to me, but the album isn’t really a political manifesto. The music is also this strange sense of loss that comes from a shift in religious identity. Loss mixed in with joy and freedom.

This is another thing I know so many people my age who grew up evangelical experience— “this thing used to mean so much to me, I got so much out of it, but was also so harmful to me. I’ve left the harmful things, should I salvage the good things? Where am I now? What do I do with all of this?”

I’m singing about these questions. The feeling of grief over losing something that gave meaning to your life, that’s a powerful feeling. And the continued search for meaning and wonder. I hope others who have felt these things can find a home in this music.

How does your music fit into the larger spectrum of folk music in America?

I think the signifier "folk" is often used nowadays to mean “a person writing songs using acoustic stringed instruments.” I do that, so it seems to be a helpful shorthand for describing the songs.

I also fingerpick when I play the guitar, and that tradition is tied to Black Gospel guitar players like Elizabeth Cotten and Mississippi John Hurt, as well as Appalachian music. A lot of that music overlaps with hymnody, which is an influence on my music.

Folk music is also often thought of regionally. I get a lot of joy out of thinking about making midwestern music. I connect the idea of midwestern earnestness to my music for sure. My bandmates and I also joke about the sound of “Midwest Guitar,” by which we mean vaguely pretty, math-rock open tuning guitar. There’s some of that in this music.

Do you have any specific reference points for your sound on this album?

I’ve always loved Sufjan Stevens, for obvious reasons. The Innocence Mission and the songs of Karen Peris are also huge for me. But my deepest influences are my bandmates. They all make incredible music, and we’ve worked alongside each other for years now, contributing to each other's respective projects.

Kenan just released an incredible album of ambient prairie counterpoint. Sam writes and records as Lo Sy Lo, and is always incubating over 100 songs. Jesse is in the band Altopalo whose process of assembling songs out of improvising is very inspiring to me, and he also makes beautiful solo music. Ethan writes operas that feel like songs that contain towns.

Do you see a divide between secular and Christian music, and if so, what are the biggest differences?

The biggest divide that I see is on the industry side— there is a Christian music industry with its own labels, publishers, radio orgs, and...this. I don’t have any interest in that world. But as far as those with a Christian identity making music, I think it functions just like any other identity.

People represent their identities in their music on a spectrum— some really lean into it, some just let it come though naturally when it wants to. And people don’t just have one identity-- my music deals with questions of religious identity directly, but is also about so many other things.

Sufjan and Karen Peris, director Terence Malick, and writer Susanna Clarke are all artists whose approach to representing their religious identity I’ve found interesting and inspiring.

Sometimes nonreligious people have a very strong aversion to music that talks earnestly about faith. Why do you think that is?

Dominant reactionary ideological systems don’t tend to produce good art. Interestingly, Christianity was formed out of Jewish resistance to a massive political empire that they were essentially occupied by — Rome. But most of U.S. Christianity at large has aligned itself with the most destructive imperialist force of our time — U.S. empire.

So unless Christian art purposefully subverts some part of the dominant system, it naturally re-emphasizes the status-quo, which is at best uninteresting, and at worse harmful propaganda.

But I actually think people do crave music that talks about spirituality in a way that is earnest and vulnerable. It’s a very human craving. Desire for meaning, desire for connection, desire for purpose. There is so much beautiful religious music that speaks to these desires.

Your Bandcamp tags "domestic mysticism" as one of the descriptors for your music. What does this mean to you? And how do you feel it lends context to your music?

Mysticism is a way of looking at the world that prioritizes a direct experience with the divine, so for me Domestic Mysticism is seeing beauty and depth and life in things around the house. Commonplace things, the things that you interact with everyday — your chairs, your windows, your doorways, your cooking items.

It’s a colorful way of saying this is homebody music, essentially. I love music that sounds like it was made in the home.

Are you playing anywhere live soon, and if so, where?

Stay on the lookout for a late fall album release show!

Anything else you want to add?

Local radio forever, CHIRP forever, onward we go, thumbs up for rock and roll.

Next entry: CHIRP Radio Weekly Voyages (Oct 4 - Oct 10)

Previous entry: Clean Cut Kid: An Appreciation of Bob Dylan’s Midlife Crisis