Now Playing

Current DJ: K-Tel

The Band Tears Of Rage from Music From Big Pink (w/ Bonus Tracks) (Capitol) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

There was a point in my life where I wanted to be a filmmaker. I still might be one at some point. Who knows? If it wasn’t for my obsession with music, I might have been a textbook cinephile by now, as intrigued by new releases and upcoming film festivals as I am now about new album releases and who’s on the program at the next big music festival.

There was a point in my life where I wanted to be a filmmaker. I still might be one at some point. Who knows? If it wasn’t for my obsession with music, I might have been a textbook cinephile by now, as intrigued by new releases and upcoming film festivals as I am now about new album releases and who’s on the program at the next big music festival.

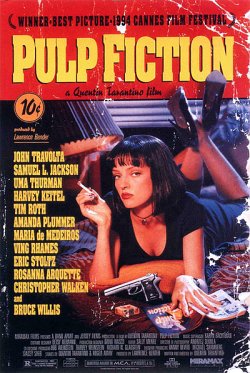

I still have a strong interest in movies, though, and the picture that got it all started for me was Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. This was the movie that not only fascinated me to no end with it’s singularly unique style (made up of entirely of, I would soon learn, styles copied from a lot of other films), but also got me interested in movies as more than just something to stare at while I stuffed my face with popcorn.

It’s a great film. But what makes a film (or a song, or an album, or a painting, etc.) “great?” A big part of the assessment is subjective, but there are some factors that go beyond personal taste, one of which I think applies here. Like Birth of a Nation, Jaws, and Star Wars, this movie changed the way Hollywood made movies. Pulp Fiction, along with other films the Miramax production company released around the same time like Sex Lies and Videotape and Good Will Hunting, introduced the idea of the independent film (which has always existed around the edges of the industry) as great way for major studios to make money. The big-budget, high-concept movies that had dominated since the ‘80s would soon have to share theater space with “edgier” projects that focused on unusual stories, quirky characters, and the elusive idea of “cool” that New Wave, Avant Garde, and foreign cinema seemed to have more of than American cinema.

In addition to its game-changing presence, Pulp Fiction succeeds due to an exceptional cast that elevated a story that could have easily ended up in the B-movie bin. It launched some actors into super-stardom (Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman) while introducing established movie names to a new generation of movie-goers and new chapters of their careers (John Travolta, Harvey Keitel).

With it’s ridiculous levels of violence and liberal use of the n-word creating plenty of controversy, the film took the entertainment world by storm, winning the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. Tarantino, the film’s director who was a video-store clerk and film nerd in his previous life, became rich and famous and successful. To me, he’s still one of the best writers in the industry, capable of making a conversation between two people more exciting than a gunfight. His love of movies, especially cult classics and B-pictures, seems to be pretty much all-consuming with him, which can be a positive and a negative. When he gets together with his buddy Robert Rodriquez (a great filmmaker in his own right), the two tend to act like two veteran DJs spinning records in a club who get so lost in their mutually epic knowledge of their genre they forget they have an audience to entertain.

While in the last couple of years Inglorious Basterds has been cited as Tarantino’s masterpiece, I must disagree. Pulp Fiction is his magnum opus. Not for nothing, this is my Ranking of Tarantino’s films:

1. Pulp Fiction

2. Kill Bill, Vol. I and II

3. Reservoir Dogs

4. Jackie Brown

5. Inglorious Basterds

6. Death Proof / Grindhouse

8. Django Unchained

An essential part of of this film that binds everything together and wraps it up in Cool is the soundtrack, which for my money is tied with Saturday Night Fever as the greatest film soundtrack ever made. Tarantino already understood the value of recontextualizing music in his earlier work, most famously giving “Stuck in the Middle With You,” a relatively benign ‘70s FM Radio hit by Stealers Wheel, a whole new meaning when he used it in a particularly gruesome scene in Reservoir Dogs. The Pulp Fiction soundtrack, which Tarantino put together with some astute filmmaking friends, his ability to find quality material for an industry that values proven commodities and flavors of the month.

Kicking off with the wicked surf-guitar runs of Dick Dale’s “Misirilou,” the album is like a Greatest Hits of Songs You Have No Reason to Know About But Man Aren’t You Glad You Do Now. It reintroduced the world to Dusty Springfield’s smoky, sensual “Son of a Preacher Man,” the raw Funk of Kool & the Gang’s “Jungle Boogie,” Ricky Nelson’s ghostly “Lonesome Town,” and the goofy but sinister-in-right light “Flowers on the Wall” by The Statler Brothers. Chuck Berry’s piano roll “You Never Can Tell” gets a deserved reissue, along with Rev. Al Green’s all-time classic “Let’s Stay Together.”

Urge Overkill’s Alternative Rock track “Girl, You’ll be a Woman Soon” still sounds to me like it needs another 10 minutes in the oven, but it doesn't take anything away from the overall collection. These are songs that would be as far away from the shelves as possible at the local record store, but they all work perfectly to create the right mood and atmosphere for the film. What makes a soundtrack great is how the songs are completely appropriate for the movie, but also stand on their own even if you’ve never seen the movie you can listen to the music stands on its own.

Pulp Fiction’s and Miramax’s success lead the way to the rise and ultimate fall of the ‘90s independent film movement.* In an effort to copy the lucrative Miramax/Disney model, every major studio quickly created or bought its own “specialty” film division that tried to copy Pulp Fiction’s freakishly massive success, mostly with varying degrees of failure. When the founders of Miramax finally split with Disney in 2005 over disputes about distribution, they took their creative energy with them. Today, filmmaking is more profitable than ever, but the major studios are making too much money with movies based on comic books, young adult novels, sequels, and remakes to bother with the risk of trying new styles, techniques, and attitudes (the kind of risks that start new artistic movements). The “buzz” that surrounded Tarantino’s radically recycled culture has proven to be a lot harder to mass produce than expected. It, like the film itself, is a great example of independent media’s ability to look around corners, dig through dustbins and find the hidden gems that end up being truly memorable all over again.

*”Independent” has a specific definition in the movie industry: it’s a film that gets less than half of its production budget from the major Hollywood studios. Miramax, the company that produced Pulp Fiction, became a subsidiary of the Disney company in 1993 but with a large degree of creative control, so it was kind of an “indie,” but not really.

BONUS: Check out Kevin Fullam’s interview with Katherine Rife on the films of Quentin Tarantino.

Next entry: Join Us for the Ravenswood ArtWalk Tour of Arts and Industry This Weekend!

Previous entry: In Rotation: Empires