Now Playing

Current DJ: K-Tel

Neko Case Margaret Vs. Pauline from Fox Confessor Brings the Flood (ANTI-) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Twice a month, CHIRP DJ and Features Co-Director Mick takes a deep dive into two albums currently in rotation on CHIRP's charts that he thinks are worth some special attention. If you haven't given these albums a listen in their entirety, let Mick make the case for why you should!

Twice a month, CHIRP DJ and Features Co-Director Mick takes a deep dive into two albums currently in rotation on CHIRP's charts that he thinks are worth some special attention. If you haven't given these albums a listen in their entirety, let Mick make the case for why you should!

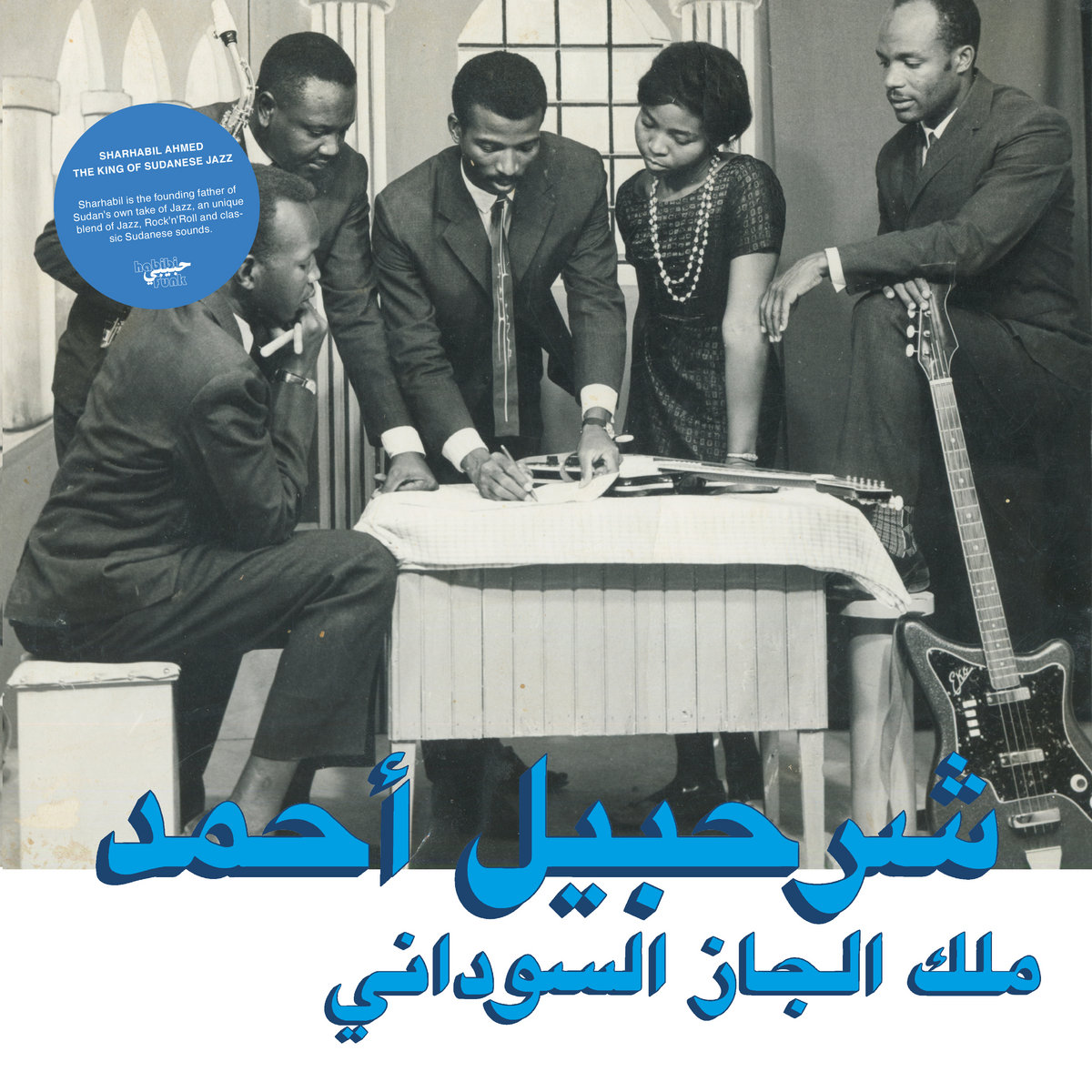

Sharhabil Ahmed

The King of Sudanese Jazz

Habibi Funk

Sharhabil Ahmed is once again holding court in his kingdom long lost to the age.

His palace has now risen like Atlantis from the briny broth of the sea or the City of Babylon from the sands of time, thanks to the relentless crate excavation efforts of Jannis Stürtz and his north-Africa allied, Berlin-based, Habibi Funk label.

Standing as the first and only proper collection of Ahmed's works to be released for mass enjoyment in the 21st Century, The King Of Sudanese Jazz is both a historical document and thoroughly tanalizing rock 'n roll record. Now in his 80s, Ahmed was, is, and will be for as long as the time permits, a man of taste and vision.

Trained in his youth in traditional Sudanese music, he learned to play the oud (a guitar-like instrument) from an early age. But before he reached adulthood, Ahmed would witness the transition of the melodic Islamic prayer to the Prophet Mohamed (madeeh) succeeded by the more popular form of the haqiba, a secular style of music that shares many of the same sonic formulas.

Although Ahmed would earn a degree in traditional music from the Khartoum University (the largest and oldest public university in Sudan), the muse for his original music would lie at the cross-roads of where east embraced west, where the psychedelia and jazz of Ethiopia flowed into the swinging swank of Billy Haley and the rattling stoptime rag and ruffle of Chuck Berry.

To thread this needle of geography and sound Ahmed would take up the electric guitar in the 1950s, a versatile instrument that would allow him to effect a perfect synthesis of rolling surf riffs and the ascendant, trance-inducing melodies of haqiba. The synthesis proved powerful enough to actually win Ahmed the title of “King of Jazz” during a competition in the '70s, a title that he retains as his own, even to this day.

The term "jazz" when applied to Ahmed’s music is obviously complicating for a Western listener. Rather than focus on the specifics of what listeners from the United States could point to in their limited experience of the genre's touchstones, it is better to take a step back to appreciate the ecumenical qualities of the folk traditions of the Americas.

Whether it be Samba, Blues, Rock ‘n Roll, or Be-Bop, Ahmed’s music catches each in his web, wrapping them in silk for safe-keeping before absorbing, metabolizing, and reproducing each in turn, albeit in a slightly skewed fashion.

Opening track “Argos Farfish” has a tight, driving blues groove, with a refreshingly light melody thanks to some fishtailing riffs that flick and tease your ears as they swim by. “Kamar Dawa” has a more overt surf influence with an enticing samba sashay, while "Malak Ya Saly" borrows lovingly from the proto-funk of Mulatu Astatke.

Working on the premise that all American folk essentially owes its origins to Africa, Ahmed’s free association of musical tinctures produces some revealing parallels to sounds that would later emerge Stateside. The compassion between “El Bambi” and Devo’s deconstruction of ‘50s Rock standards, particularly “Praying Hands” off their debut Q: Are We Not Men? is striking, perplexing, but ultimately appreciable for its predictive properties.

While Devo’s assessment of humanity and her potential has been historically bleaker, the interrogation of our shared human conditions across culture, time, and space is a central facet of Ahmed’s body of work. What separates the brotherhood and sisterhood of humanity, when we can all speak the universal language of song?

Without begging the question further, I believe that Ahmed would agree with my assessment that music is the embodiment of the uniting passion of the human spirit. A transcendent force through which everyone may come to recognizance the instrumentality and fulfillment of themselves and others. In the court of the King of Jazz, all shall find themselves recognized.

Mick is always writing about something he's heard. Possibly even something you'd like. You can read his stuff over at the I Thought I Heard a Sound blog.

Next entry: The “Exit West” Playlist

Previous entry: Critical Rotation: “Chicago Waves” by Carlos Niño and Miguel Atwood-Ferguson