Now Playing

Current DJ: Commodore Jones

SZA Kill Bill from SOS (Top Dawg Entertainment/RCA) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

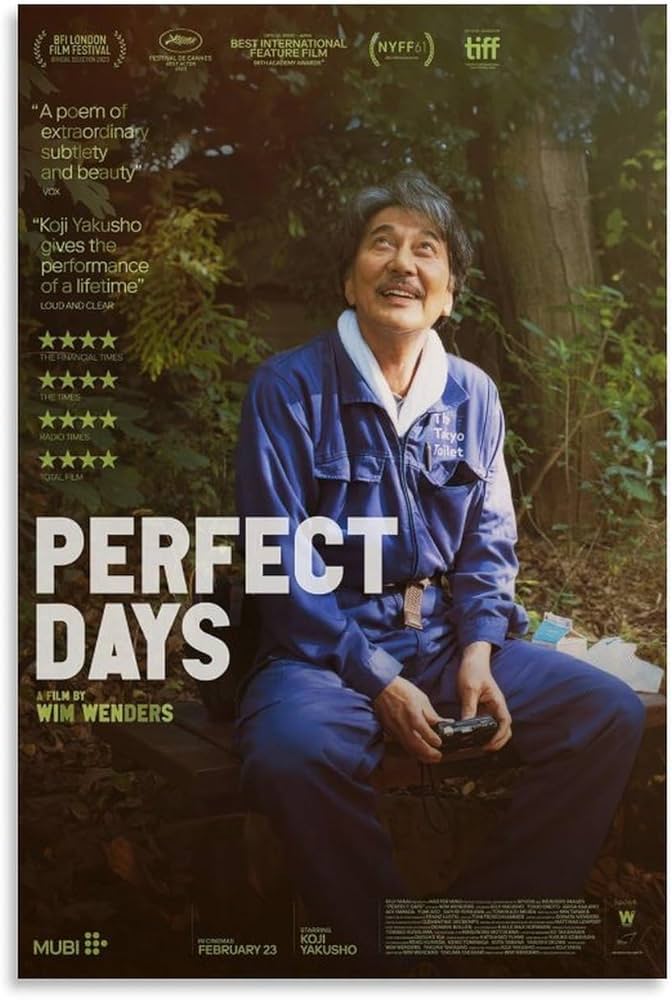

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 2023 Drama Perfect Days.

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 2023 Drama Perfect Days.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

I've never been one for nature documentaries*. Sorry, folks, but animals are not captivating figures to yours truly. They graze, they run around... but mostly they sleep, right? Of course, I haven't spent much time with animals outside of my dinner plate. For the most part, they make me a bit uncomfortable, such that I reflexively pull my hands towards my chest when passing dogs on the sidewalk. Young Kevin was never, ever interested in feeding sheep at the petting zoo. Why tempt fate by sticking one's fingers anywhere near a creature's mouth?

[*Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man is the exception here, but really, it's a film that's more about the kooky protagonist than the bears he was enamored with.]

Why do I bring this up? Because long stretches of Wim Wenders' Perfect Days could be construed as a nature doc. "Hirayama: A Life -- the habits and rituals of a Tokyo toilet cleaner." We watch Hirayama (Kōji Yakusho) wake up. Brush his teeth. Get dressed. Drive to work. Clean toilets. Afterwards, there's an evening structure as well. Onsen bath. Dinner. Reading. Sleep. Repeat. The process largely plays out without much discernible input from Hirayama himself. His dialogue is minimal, and is practically non-existent during the opening half hour.

It sounds riveting, I'm sure! Well... it is riveting. Wenders lets us get intimately acquainted with Hirayami before revealing his backstory in dribs and drabs. He cranks up Nina Simone and Lou Reed via his van's cassette deck. He snaps pictures with a vintage camera during lunchtime excursions, and catalogues them meticulously after he picks up the developed photos. Above all, he is serious about his craft. Hirayami takes pride in his work, and if you mess with him while he's on the job, he will feel pain.

Perfect Days is a character study within a larger love letter to Japanese culture. It should be noted that these are no ordinary bathrooms that Hirayami is cleaning -- they're part of The Tokyo Toilet, a collection of aesthetically-pleasing restrooms designed by top Japanese architects. Originally, Wenders was tasked with the assignment of creating a short film about the project, but he was so smitten that he decided to construct a narrative film around the subject instead.

[As an aside here, I spent two weeks in Japan this fall, and beyond the food (otherworldly), beyond the technology (seemingly decades ahead of America), beyond the unfailing politeness and decency of passersby (imagine an inverse NYC), the one quality I would chose above all others to import to the States would be the cleanliness. It's ridiculous. I simply didn't see trash in Kyoto. Nor trash cans, for that matter. One could eat off the Tokyo subway floors. And the public restrooms? Spotless. Each and every one I visited. Reflect upon your own experiences stateside, and let that sink in.]

Before we tackle the whos and whys of this movie:

* Clarence, where does this rank as far as the "quietest" films you've seen? My personal champ, never to be dethroned: Chinese Portrait, which was 79 minutes of... er, wordless portraits of Chinese citizens. Truth in advertising! Wenders has commented on the power of Kōji Yakusho's eyes -- it's those eyes that are able to tell the story. Can you think of any Western actors who have a similar ability to impart so much without speaking?

* What did you think about the role of music in the film? It's a killer soundtrack, for sure, though it was a bit of a head-scratcher why there would be such a lucrative market for Hirayami's vintage cassettes. Cassettes fall apart over time! Who out there is paying top dollar for an Otis Redding tape as opposed to a vinyl copy?

* Perfect Days kicks into another gear when Hirayami's teenage niece shows up, and it's refreshing that, far from being ashamed that her uncle cleans bathrooms for a living, she cheerfully accompanies him for a couple of days. When her mom arrives, we get a clearer sense of what Hirayami's "former life" was like; apparently, his past was much more extensively fleshed out during production. Does that snippet of biographical flavor in the film shift your impression of his character in any particular direction?

Clarence:

Over the past few months, I’ve read some articles about how there's an emerging market for cassette tapes, not as strong as this movie portrays it, but there's definitely interest out there. The main reason is because cassettes are becoming so rare now, and people have to put their speculation money somewhere…! I've still got a bunch of them from my younger days, but I'm not ready to part ways with them yet.

That Hirayama has a killer retro-formatted music collection doesn’t surprise me. It fits right in with his artistic sensibilities. Along with the “quirky” job, his life is filled with literature, music, tending to his plants, and photography. There is no “hero’s journey” for him to embark on, in the modern film sense of the term. In a world where everyone’s supposed to be striving and suffering and climbing over each other to have more and be more, Hirayama seems to have found his best life and is living it. It’s a rare style of movie.

It’s also so non-Western. Throughout the movie, Hirayama is put in situations where he could get more involved by taking an action or starting a conversation that would lead to an entirely different story, but when he’s not being helpful or generous in the moment, he chooses instead to observe the people around him. And that’s enough.

Hirayama’s a modern-day kind of monk, and I found watching him go about his days to be soothing and poetic. Kōji Yakusho’s masterful performance is definitely a reason why. I could have seen Phillip Seymour Hoffman taking on this kind of role and story, or maybe Forest Whitaker – actors who don’t need to rely on bluster or Method overkill to communicate with an audience.

It makes for a weird, or should I say, different movie-watching experience. The only other film I can think of like it is Happy Go Lucky (2008), whose protagonist is also someone who reflexively chooses to live on the bright side of things and not let negative energies affect how they move through the world.

Hirayama is definitely happy with his life. As in, “wake up every morning with a smile on your face” happy. Or is he…? This gets into the why of it all. His experience with his niece and brief encounter with his sister do bring up interesting questions that may or may not echo to the present day.

Everybody has an origin story, and it seems like Hirayama’s would reveal much about how he found his way to the life he’s currently living. But I feel like knowing more about what makes him tick would take some of the magic out of experiencing the simple act of watching him live his life.

What do you think, Kevin? Would knowing more about his past enhance the experience for you? And would this story have worked as well if Hirayama had a different job? I feel like there’s some meaning behind the work Hirayama does – cleaning public toilets. Do you see anything of import there?

Kevin:

Great observation about Hirayama being a "modern-day monk," Clarence -- I totally agree. Beyond his low-key optimism, there's also a certain patience in his approach to the world. Is it a coincidence that you never, ever see him on the internet? While he does possess a cell phone, it's used strictly for verbal communication... and sparingly at that, given his lack of loquaciousness.

I'm of the belief that we get just enough nuggets of Hirayama's past to piece together a likely scenario. A rich family and an emotionally abusive father? Boom. Not only did the father not even need to appear, but his abuse was merely hinted at. "He no longer recognizes anything... he won't act like he used to." When Hirayama still refuses to see him, we know the wounds are deep indeed.

[While I often crave exposition, sometimes getting what we want isn't a good thing! "Show, don't tell" is an adage of filmmaking. One of the components I loved about Richard Linklater's Boyhood is that he respected the audience to "fill in the gaps" when there were chronological jumps in the story.]

Beyond the fact that Perfect Days began as a film about the "Tokyo Toilet Project," I think the toilet-cleaning is an essential component to how we view Hirayama. It's a job where:

A) The work is solitary.

B) It's considered one of the least prestigious jobs in society.

C) There's a great deal of latitude with regards to the effort that one puts in.

Point C is critical here. There are a lot of jobs that people would consider to be "undesirable" -- few folks are chomping at the bit to work in a garment factory or pick up garbage. But in those tasks, you're pretty much just cranking out widgets. (Forgive my ignorance if I'm wildly off-base here!)

While I'm sure that there's a "baseline" of restroom-cleaning that has to be accomplished for the higher-ups not to notice, it's clear that Hirayama goes above and beyond the call. How can we not be in awe of his use of inspection mirrors re: hard-to-reach spots on fixtures? It also helps that these aren't normal facilities that he cleans. If you're going to employ the most dedicated lavatory cleaner in town, wouldn't you want him at the Tokyo Toilet Project instead of some generic airport bathroom?

Hirayama's tale also reminded me of the story of Geoffrey Owens, who was once a star on The Cosby Show but was "outed" in 2018 as an employee of Trader Joe's.

“A lot of good things happened to me, but the best thing about that whole thing was that people started thinking about and talking about work in a different way. They started considering the dignity of work — even the nobility of work. Considering that some jobs are not necessarily better than others, and that — let’s put it this way — all work matters.”

The gastroenterologist who performs colonoscopies is doing work that's not all that far removed from Hirayama's occupation, yet we attach far more status to it. Medicine in general used to be considered a trade rather than a white-collar job, and I wonder how much of that shifting perception has impacted what we're willing to pay in health-care costs. Hmm.

Some final questions about the film itself:

1) Where did you stand as far as Hirayama's assistant, Takashi? I've long voiced my objection to "comic relief" in dramatic cinema, and I will not deviate from that position here. Thankfully, he was written out of the story about halfway through, though I was far more intrigued by the no-nonsense lady who teams up with him at the end of the film. Finally, a worthy partner for our hero!

2) "Or is he...?," you asked on the subject of Hirayama's happiness. He's not outwardly striving to "achieve," but I get the impression that he still seeks companionship? At the very least, he harbors a bit of a crush on the female restaurateur that he frequents on weekends. Maybe in a Western-style film, there would be more of a Meet Cute that got them together, but thankfully such tropes were sidestepped here.

3) The final scene where Hirayama expresses the full gamut of emotion, from smiles to tears, while driving his van -- what did you make of it? Can you think of anything comparable in cinema?

Clarence:

The only other film where I remember a final scene like that is Platoon (1986), when Charlie Sheen's character is airlifted off the battlefield after most of his unit is killed in action. There's an obvious sense of relief and catharsis as he finally has time to sit and think about what he just went through. That's the only kind of scene these two films have in common, but it can be a nice showcase for an actor to show their character thinking and reacting to those thoughts.

Back to Hirayama - I think he has a fondness for the restaurant owner, but it may be more because of the routine she provides (a hot meal, entertaining conversation) rather than a romantic attachment. Whatever may or may not have happened to him in the past, his life is extremely ordered, and the things that contribute to that sense of order are valued by him.

Artists and other kinds of creatives and deep thinkers tend to enjoy not having to worry about random stuff happening to them. I remember in a documentary how Ian Curtis, the legendary front man for Joy Division, commented how he used to work in a factory when he was young and how much he liked it because he could dream all day while he was working. There's something poignant to consider in that.

[I also heard somewhere that one of the most popular jobs for high-IQ people is driving a taxi cab, maybe for similar reasons. I'd have to check on that, though.]

"...all work matters..." - what a great quote. Something else to consider is how Hirayama's job is actually very important, considering how uncleaned, undersupplied public restrooms are not just unpleasant to use but can also become public health hazards by helping spread diseases like flu or even COVID. Many societies will look down on jobs that involve cleaning things, but will notice when those jobs stop getting done. I still remember when the garbage haulers in Chicago went on strike in 2003. You can keep your white collar professionals and entrepreneurs - PLEASE keep the garbagemen doing their jobs!

In that sense, it's great how Hirayama cares enough about his work that he fashions tools to make him even more effective. His assistant clearly doesn't care as much, but that struck me as a realistic stance from his character. You're right, he could have easily become an irritant, but I thought the actor played it pretty much just right. Hopefully the character appreciated having someone like Hirayama around to help him out!

By the end of the movie, I felt while there was still a lot we didn't know about this toilet-cleaning artistic loner, we got a magnificent portrait of him and what makes him tick. I can see how the lack of conflict or romantic hijinks would keep American studios well clear of it, but it's one of the best character studies I've seen in a while.

Next entry: CHIRP Radio’s Best of 2024: Matt Barr

Previous entry: CHIRP Radio’s Best of 2024: Eric Wiersema