Now Playing

Current DJ: K-Tel

The English Beat Mirror In The Bathroom from I Just Can't Stop It (Go Feet) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 2021 film After Yang.

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 2021 film After Yang.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Bobby Evers.

________________________________________________________________

"Are you happy, Yang?"

-- "I don't know if that's the question for me."

-------

"Did he ever want to be human?"

-- "That's such a human thing to ask, isn't it? We always assume that other beings would want to be human. What's so great about being human?"

________________________________________________________________

Kevin:

As the idea of artificial intelligence and androids comes closer to fruition, we seem to be shifting to a kinder, gentler species of robots in Hollywood, no?

The days of T-800s and renegade replicants are on the wane, while a growing number of today's celluloid "technos" -- whether they exist in the ether as in Her, or in corporeal form like the title character of After Yang -- no longer have designs on world domination. As Samantha of Her alludes to, well... what would be the point from a computer's point of view? It's far more likely that an autonomous AI would consider humans not worth the bother. What Yang and others of its ilk can offer us, however, is reflection on what it means to be human.

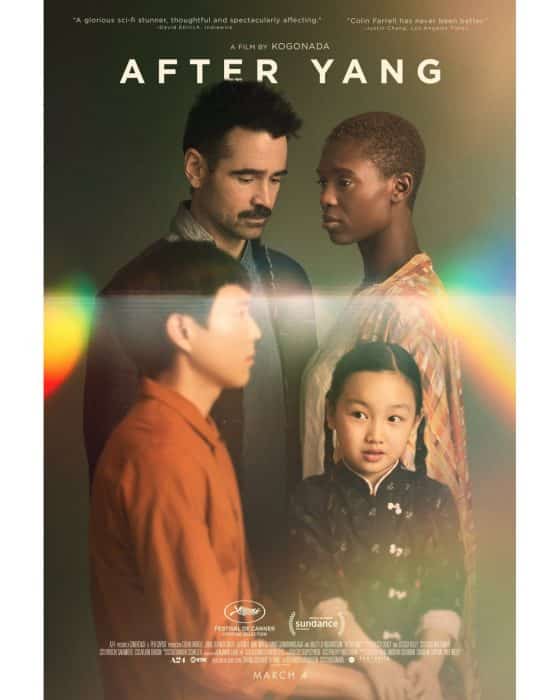

In After Yang, Jake (Colin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith) live in the near future with their adopted daughter Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja) of Chinese descent. When Mika joined the family, her parents purchased a robotic "sibling," Yang (Justin H. Min), who was programmed to not only be a companion, but also to teach his sister about Chinese culture.

Early in the film, Yang goes on the fritz, and despite the best efforts of local grease monkeys, he can't be revived. During the tinkering, however, a hidden camera is found within Yang which doubles as a "memory bank." Yang's model predates legislation which outlawed such devices; each day, the memory bank is able to store a short clip of whatever he deems important.

As Jake begins to explore these memories, the relationship between Yang and his family is revealed within a series of flashbacks. What did Yang find meaningful in his existence? Was he ever troubled by the limitations of his programming? And why do so many memories feature Ada (Haley Lu Richardson), a local barista?

When you start thinking about our own programming (hey, we have genes!) and the human body as a machine -- complete with a heart that generates an electrical impulse -- well, how much are we different from technos? Yang doesn't have free will... but many scientists don't believe that we do, either. And while he seems unable to answer broad, ambiguous questions such as whether he's "happy," I'm guessing that many humans would likely have similar difficulties with such queries as well.

-- Bobby, what did you think of the film, both on its own and in relation to other tales about robots? Do you think that Yang is the sort of creation that we're heading towards as a society? Would you be comfortable with a Yang-like machine in your home?

-- Jake mentions that Yang often asked, "What makes someone Asian?" From his perspective, his makers simply wrapped their machine inside an Asian face. Is it possible for creators to imbue a machine with "Asian" culture and/or thinking? How would we define such a thing? And why is it that important for Mika to learn about her Asian roots? We're living in America, and I'd posit that after a couple of generations, nobody cares much where one's ancestors hail from, whether it's Colombia or Belgium or Sierra Leone.

On a similar note, is there significance to the fact that Mika's parents are of different races? (I'm guessing this was a conscious narrative choice?)

-- Towards the latter third of the film, we see flashbacks of Yang's interactions with the family where various exchanges are quickly echoed, akin to a record skip that takes a conversation down a slightly different path. Yang might be talking with Kyra about butterflies, where we'll hear a line uttered one way... and then again with a different inflection. What do you think was going on there?

Bobby:

This film is truly unique and original (aside from being based on a short story). The storytelling choices, both what they revealed and what they withheld, did a lot of the heavy lifting as far as the world of After Yang.

For starters, there's a very large Asian influence on American culture in this future -- everything from Jake's tea shop, to the child he and Kyra adopted, to even the pop culture they partake in as a family. And so Yang is "adopted" to serve as a sort of Alexa to educate Mika about Chinese culture.

But then he truly does become a sibling to her. Everyone whom Jake consults seems confused as to why the family is so attached to Yang, as if he were more like an Alexa and less like a relative; for us, the audience, it's like, "how can these jerks be so cold?" But we would also never think of ourselves as "attached" to our Amazon Echos.

There's also a detective story here. Jake sets out to try and repair Yang, but then uncovers a bigger mystery: who was the Yang that existed in the rich interior of his AI life? And who is the girl he was pursuing? Early on, Yang is largely absent from the movie, because his story doesn't truly really start until after he's shorted out, so we don't spend a bunch of time getting to know him.

Once we meet the real Yang via saved memories and recollections, we form a deeper attachment to him ourselves. When you said that Yang didn't have free will, I wondered if that's actually true. It seemed like he was still drawn to the coffee shop where Ada worked, and pursued a friendship with her. I feel like those are choices he made.

Regarding how this story fits with other robot stories, I think you're right on the money with the Her comparison. Yang doesn't aspire to world domination like robots in The Terminator or The Matrix. He just wants to vibe and provide cool facts about flora, and I think that's great. So, stop me if this is too English major-y.

I have this theory about robots-taking-over plots. In the 1800s in America, there was a lot of white anxiety about slave uprisings. It even appeared in fiction like Mellville's Benito Cereno, and various other stories. And so what has supplanted that is anxiety about subservient machines rising up, perhaps most notably in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Or even before that with Frankenstein's Monster? It gets a little tired after a century and a half -- Man's hubris regarding his creations, which wind up turning against him.

Maybe we should be less anxious about what is going to befall us, and more concerned with the fact that we might have it coming? Point is... I love stories that subvert expectations and upend traditional formulas. Yang's rebellion was essentially one of finding love -- that's such a good rebellion.

Another thing I wanted to add is that my favorite science fiction involves tales where the "science" is not the focus, but rather just the setting where a very human story is taking place in, and this scratches that itch for me. After Yang paints us a picture of this future world, but ultimately you're trying to understand a person you love, take stock of their importance in your life, and figure out how to grieve and carry on.

And yes, those record skips were interesting. Maybe they were indicating the many lives Yang had lived before, or showing us what it was like to live inside his head? It was not clear. What do you think?

Kevin:

Early on in After Yang, there's a brief snippet of a bulletin board in Mika's room -- pinned to it is a newspaper which implied that China and America had been at war for 60 years. This lends the question, how did a war that long between two superpowers not go nuclear? And wouldn't it be strange for the US to accept Chinese babies during the aftermath? I can't quite imagine America building Japanese-looking robots to serve as siblings in the wake of Pearl Harbor, for instance.

Sci-fi in general has been ahead of the curve in terms of predicting the impact of China on future civilizations. Firefly and The Expanse, for example, featured worlds where Chinese culture and language were very much a part of the public lexicon. Relatedly, the rise of Chinese nationalism in recent years has meant that cinematic imports into that country have come under increasing scrutiny -- so much so that Hollywood often censors itself to avoid running afoul of Beijing's Culture Police. If After Yang had been a big-budget movie with blockbuster aspirations, it's a safe bet that any allusions to a Chinese/American war would've long been excised from the script.

As far as Yang and free will... perhaps he had "free will" within strict parameters? He's not programmed to consider his own happiness or unhappiness. Nor is he allowed to lie. (Though when interacting with little kids, there's obviously a great deal of latitude in terms of how he answers questions.)

That's an interesting take as far as Yang "rebelling" via a search for love! It opens up all sorts of questions. Could Yang even define "love?" Or maybe his inability to do so would fill him with distress, the same way he was unable to fully appreciate Jake's love for tea?

Of course, how well could any of us red-blooded humans define something like love? I'm guessing that if you polled a dozen people on the street, you might get a dozen different answers. And just as many quizzical responses. Can there be real love without emotions like anger and hate, which presumably Yang wouldn't be able to express?

By the way, I'd suggest that one could go all the way back to Jewish folklore with regards to tales about Golems as creatures that run amok once given life. But, like you, I'm very happy that the narrative didn't travel down this oft-worn path, and instead centered around a tale that encourages viewers to examine all sorts of questions about the human condition.

Next entry: CHIRP Radio Weekly Voyages (May 2 - May 8)

Previous entry: The CHIRP Radio Interview: a Light Sleeper