Now Playing

Current DJ: DJ M-Dash

Rogê Old Diamond West from Curyman II (Diamond West) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the NetFlix documentary 13th.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

Kevin:

Truth can be a murky concept. Truth when it comes to politics? Well, lots of folks might chuckle at that association, right? Back in the '90s, I enjoyed Michael Moore's political documentaries (particularly his first, Roger & Me), until I realized that I was really only getting a slice of the story... namely, the slice that supported his anti-corporate polemics. Moore was a very funny filmmaker in those days, and offered up plenty of clever critiques of American culture in general. Was it fair to call Corporate America on the carpet for its misdeeds? Absolutely. Were the issues discussed in his work much more nuanced than he led people to believe? Again, absolutely .

One complicating factor is that we all bring our own biases and backgrounds into political discussions. My worldview and set of experiences might be dramatically different than someone else's. When it comes to turning a critical eye on a non-political movie like The Rider , this difference may not matter much -- how many of us know anything about horses, rodeo, and living in the Dakotas? But I'm a student of history and government, and thus I'm going to be much more guarded when it comes to political arguments that someone else is selling me.

Granted, like I said -- my own viewpoint is full of bias! And it doesn't help that I tend to be a contrarian in general. There's no pure "objective" lens through which to view politics, and that's part of what makes the topic so damn interesting... and frustrating. So, how should one evaluate agitprop films?

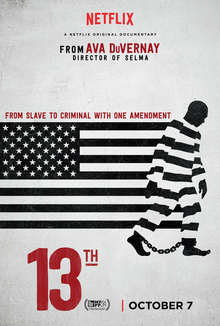

This brings me to 13th, a 2016 documentary from director Ana DuVernay about the historical relationship between the criminal justice system and America's black community. The "13th" in question refers to the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which freed the slaves in 1865. DuVernay posits that this landmark legislation simply encouraged the United States to adopt a different stratagem; in lieu of slavery, Uncle Sam could simply jail large swaths of the country's black citizens under the guise of law enforcement, with the help of corrupt government officials from local police up through the FBI. And, DuVernay asserts, when this abuse waned after the reforms of the civil-rights era, Congress stepped in to pick up the slack in the guise of sweeping anti-drug statutes that disproportionally affected the black community.

It's a compelling launching point for a discussion, and 13th is a visually arresting work (no pun intended) that raises a number of thought-provoking questions. Was the War on Drugs, along with other anti-crime legislation, racially motivated? What is the social impact of private-prison systems, and who benefits? And, how much has changed as far as progress on civil rights issues over the past half-century?

And here's where things get complicated. (Again, remember my contrarian nature.) DuVernay focuses on the Nixon administration and suggests that the opening salvos in the War on Drugs were largely race-based, but the explosion of urban crime was a very real problem from the late 1960s up through the '90s, and urban residents (many of them minorities) felt " under threat " from the drug trade.

Most of DuVernay's guns are aimed at the right throughout the film, but the Clintons also receive a fair share of criticism for championing the 1994 crime bill which included the famous "three strikes provision." Was this fair? I would've loved to have seen the viewpoint of academics like Michael Fortner in the mix; Fortner has argued that the impact on black communities were largely " unintended consequences ," and that "life in the inner city was just untenable" at the time. Who's speaking up for the folks who wanted drugs (and more importantly, the violence surrounding the drug trade) out of their neighborhoods?

What also can't be denied is that America has gotten safer over the last 25 years. I wouldn't be so quick as to give all the credit to law enforcement -- but wouldn't it be at least a pertinent point to raise in the discussion? Same with the stats on private prisons, which DuVernay lambasts throughout the documentary. I'm not a huge fan of the concept of private prisons, but national scourge this is not -- Pew reports that just 8% of prisoners are held in private prisons, and that their numbers are falling. And on that note, are we still seeing an explosion in the number of incarcerated individuals? Not according to this Wiki timeline , which states that the number of people in the prison system has pretty much leveled off over the last couple of decades.

I have lots more to say about the juxtaposition of interviews and framing devices, but let me turn it over to you, Clarence, for your thoughts. Before I do, though -- a while back, we discussed the documentary The Thin Blue Line, during which I mentioned my love of another true-crime doc, The Staircase. Since The Staircase series has recently been re-released with additional episodes, it's back in the news -- and apparently there were lots of critical bits of info that were omitted from the film . Very disappointing for me to hear, and it's made me a bit jaded on the art form at the moment.

Clarence:

I'm glad you mentioned The Thin Blue Line, Kevin, because that was one film that really hit home the idea of subjectivity and motive in filmmaking. I agree with you, I don't think there is a way to be purely objective in politics or any form of communication for that matter, including journalism, a profession that claims to have that goal. We're all coming from our own point of view, not just in how we describe things but in what we choose to pay attention to.

That being said, I think DuVernay's film is fantastic. I think about this film and its methodical analysis alongside works such as I Am Not Your Negro (poetic history) and O.J.: Made in America (pop biography) and I marvel at the new era we're living in now. '70s Blaxsplotation was all about “black films about black people for black people.” These new projects are “black films about black people for EVERYONE” where film makers can explain society and history the way they see it, without having to filter it through a lens of mainstream (i.e. “White”) approval.

This documentary does a lot of historical dot-connecting, and the case made by the group of scholars and activists is (to me) convincing, depressing, and damning. There's room for interpretation of events, but not a lot of room when, for example, we hear Presidential advisors directly advocating going after The Negroes in order to build support to win elections.

A word the film doesn't use (I think intentionally) to describe the Negro's centuries-long situation in America is “conspiracy,” but that sentiment has been around ever since the first African slaves set foot on America's shores. For example, there's evidence (depicted in dramatic and documentary form) that the CIA did, in fact, knowingly help fuel the inner city drug problems over the decades. Far fetched? Maybe. Almost as much as using poor black people as human guinea pigs to study disease .

Speaking of the inner city, I think the drop in crime can be traced to the fact that not as many people are being locked up for minor offenses like having or using drugs. I think as more states legalize the use of marijuana, we're going to see incarceration rates drop even more. [Cynical people will point out that this didn't start happening until the poverty-drugs-prison-poverty cycle started affecting large numbers of white communities with the Oxycontin epidemic.]

I think more than a few of the folks who live in inner city neighborhoods would point out that one reason there's so much violence is a distinct lack of a police presence in their neighborhoods. Not tactical SWAT teams swooping in to make drug busts, but regular daily interactions with the people who live there. I live in the Egdewater/Andersonville area, where police are always minutes away if there's trouble. Not the case on the South and West sides.

Back to the doc... I was struck by the feeble retorts of the ultra-conservative talking heads who were given a chance to rebut the unwinding analysis and whose only response is basically “No. You're wrong. It's not like that. You're silly. [Sticking fingers in ears] LaLaLaLaLa...!” [When NEWT GINGRICH is comfortable acknowledging the presence of systemic racial bias in America, something's going on.]

But let's maintain the subjectivity we both agree is a fundamental part of politics. What would you say, Kevin, might be the counter-argument to this documentary? If someone hired you to go out and find a bunch of people to argue “the other side,” what would it be and how would you do it?

Kevin:

Well, I think a documentary that is entirely a counterargument to 13th would be a disservice in the opposite direction; I'd much prefer a film which left the viewer with questions, as opposed to one which served up straw-man arguments for the director to easily dismiss. So, ideally, I'd also focus on the very real concerns about drugs and violence that many folks in the black community felt at the time, and blend some other voices with those of DuVernay's work? Voices of minorities who might have different opinions from those in the film on the causes of crime and the proposed government solutions, and are perhaps much more compelling than those of Grover Norquist and Michael Hough, the conservative sacrificial lambs in the film. As far as the latter -- did DuVernay interview a dozen advocates for ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative advocacy group which 13th claims is responsible for what some argue is anti-black legislation) and then settle on the pastiest, most unconvincing speaker for the final cut?

[I often do wonder about the footage that's left out of these projects. Years ago, I spent a few months at Kartemquin Films during a time when they were doing post-production for their Steve James film about Chicago gang violence, The Interrupters. I transcribed one particular interview with an ex-gang member, Eddie Bocanegra, who talked about the fact that he had plenty of good role models in his home and community, and how he blamed no one but himself for his poor choices as a teenager. He was a big part of the finished film... so I found it interesting that this admission wasn't included, especially since it seemed to counter the tone of the rest of the movie.]

If it were me, I'd also separate the judicial/economic arguments which run through the film? The latter is a polarizing one, depending on where you stand on the Great Society, the War on Poverty, capitalism, globalization, and everything in between. I'm a regular reader of Reason, so you and I (and DuVernay, it seems) are certainly going to have different views on the impact of economic policy on crime and the black community. (Which is perfectly OK! The difference of opinions, that is, not the crime.)

However, I do wholeheartedly agree that the War on Drugs is a failure, and that drugs should probably be treated as a health issue as opposed to a criminal one. However, what's the government to do when violence is involved in the drug trade? And here's where it gets uncomfortable re: issues of race. Newt Gingrich was absolutely right about the double-standard with regards to disproportionate crack and cocaine penalties*, and how the former is far more harmful to black communities than white. The question I have is, would the laws be more equitable if rich communities saw similar levels of violence re: the cocaine (or heroin) trades? I'm reminded of Taxi Driver and Pulp Fiction, and how none of the drugs there were sold on the street; the customers were in hotels or middle-class homes. Nobody was warring over corners, a la The Wire. Territory meant nothing.

[*He was also right that no white person knows what it's like to be black in America. That, I'm sure everyone can agree on.]

But the way to deal with the violence is drug legalization, which most Americans don't seem to be able to stomach beyond marijuana. Is that the way to go, to let people kill themselves if they wish? I'm always going to lean towards more freedom of choice than less, but again... that also could involve uncomfortable ramifications.

Clarence, you bring up a great point re: the varying levels of police presence in Chicago neighborhoods. I'm going to go out on a limb and guess that your average teenager in Edgewater is likely to have a much more positive view of a police officer than a teenager in Englewood might have. Obviously, the police have a certain history of being "unkind" to minority communities. But places like Englewood are where the crime is happening -- which require an aggressive law enforcement stance, right? How can we improve the relationship between the two sides in these areas? Is such a thing even possible? And let me tie this into music and culture as well, since it's no secret that certain brands of hip-hop encourage antipathy towards law enforcement among younger folks, who are more likely to be the ones caught up in criminal activity. Is this a chicken-or-the-egg question? Can crime-ridden areas improve, absent some sort of population migration or aging? Does CHIRP have a sociologist on staff? I've got nothing but questions here...

Also, you mentioned I Am Not Your Negro, which we discussed on this very blog last year, and I appreciated a great deal more than 13th. To me, James Baldwin's words were much more effective in articulating the pain felt by those who've been subjected to America's racism. Perhaps I also felt more sympathy for an educated, accomplished writer as opposed to a faceless drug user, non-violent or otherwise? And so this is another area where I felt 13th went astray, in comparing the coordinated attack on members of the '60s civil-rights movement with the random police brutality cases today.

Clarence:

When I think about what happened to Laquon McDonald, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, Philando Castile, and on and on and on, it resonates with me how 13th is making the case that these attacks are in essence coordinated by a system that implicitly says to uniformed officers that dark skin allows for more force and less restraint on the part of cops. The end result is the same as a racist mob attacking someone on the spur of the moment.

Also, I think it was entirely appropriate for DuVernay to include the voices of the far-right think tanks and legislative groups, because for all their sliminess, those are the people who wield real power in Washington. Representation for poor people on Capitol Hill as far as economic policy, regardless of race, is exactly zero. But that was the case when the Constitution was written, wasn't it? At some point maybe we could be honest about how “all men created equal” really means “men with wealth?”

Speaking of which, as far as the situation in Chicago, one of my favorite aphorisms of recent years is from the sports pundit Tony Kornheiser, “The answer to every question you have is money.” To understand what's going on in our town, all you need to do is take a heat map of the highest crime areas in Chicago and overlay it with a heat map of how much is paid by each neighborhood in property taxes. The neighborhoods that pay the most get the most protection. They also get the best public schools, most up-to-date roadwork and street lighting, and all the other goodies that make some parts of Chicago an urban utopia. Those poor Black and Latino folks on the South and West sides of town don't put tax dollars into the coffers (or donation dollars into politicians' pockets), so they don't get the stuff the neighborhoods you and I live in.

Years ago I was listening to a radio show that had a guest on who was a long-time police chief (speaking anonymously) who believed EVERY drug should be legalized. His rationale, which I agree with to this day, is that the police should exist to protect us from each other, not from ourselves and our bad habits. The reality is that people kill themselves all the time whether through literal means or indirectly through drinking too much, not exercising, etc. To even attempt to construct a police system that monitors and controls all of these aspects of our lives is to invent the kind of controlled society that liberals are always being accused of desiring.

So what the hell do we do about all this? I think part of the solution is to keep talking and keep expressing our point of view, as DuVernay does in her movie and we do with this series. I do agree with you, Kevin, that when the narrative is coming from one person like Baldwin describing his own life, it's easier to avoid the traps that come with trying to speak for other people. And yet, when someone sees a pattern, that can help inform our individual circumstances, as long as we keep our ears and minds open.

One more thing – watching 13th, I couldn't help but think of how it wasn't too long ago that these kinds of in-depth documentaries would feature an all-male, all-White lineup of experts and pundits, with maybe a token Black community member or activist thrown in. Even if nothing was settled, seeing this particular group of thinkers address this century-long issue made me feel like we...ALL of us...are moving in the right direction when it comes to the conversation about race.

Did you see the movie? Want to add to the conversation? Leave a comment below!

Next entry: @CHIRPRadio (Week of July 30)

Previous entry: Grumble Channels James Seminara’s Storyteller Side