Now Playing

Current DJ: Chris Siuty

Tuff Sudz Eyelids from Tough Suds (Tough Soundz) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Written over the course of pandemic and published today, December 1, Bradley Morgan’s new book U2’s The Joshua Tree: Planting Roots in Mythic America takes a critical look at the monumental album and how its call for justice in 1987 continues to resonate in an America shaped by the election of President Donald Trump.

Written over the course of pandemic and published today, December 1, Bradley Morgan’s new book U2’s The Joshua Tree: Planting Roots in Mythic America takes a critical look at the monumental album and how its call for justice in 1987 continues to resonate in an America shaped by the election of President Donald Trump.

Out today, Bradley's book offers a historical perspective on the circumstances and policy that allowed us to get where we are, and invites its readers to remain steadfast in hope and their belief in the human spirit.

I sat down with Bradley over Zoom to discuss the scope of the book, its message as told through The Joshua Tree, and how the legacies of the Reagan and Trump administrations continue to have global repercussions.

So, how do you feel? I've been following your posts about the numbers the book is doing leading up to the publishing date, and you are definitely making a mark. I would love to hear about your feelings on where you're at now with your relationship to the book, and your reaction to how, 11 months into Joe Biden's presidency, much of the work still applies.

To understand my relationship to this book, you have to take into consideration the journey I've taken to write it.

Prior to getting this published, I had never been a professional writer outside of a few pieces published here or there, so I didn't have much of a network. And when you're writing a book, it's not just about the quality of the writing but the pipelines of access to publishing resources.

So during that time, you’re going through a very isolated process because in writing you’re alone all the time. You have to reconcile your own issues and insecurities in order to get to a place where you have confidence in your writing. And even after getting a publishing contract, there are still ways in which your confidence can be shaken.

To give you an example, when the January 6 insurrection happened, I had a hard time believing in the idealistic aspects of America—so much so that I called my publisher and asked that we discuss what was happening.

A lot of what I write about is reconciling the mythological vision of America with the reality of America, and dealing with the responsibilities we have not just as Americans but as individuals in a global society.

So when I was talking to my publisher, he said, “I never told you why I bought your book. It’s because you’re very much concerned with universal truth, and that shines through.” And we had a long conversation about how democracy is messy when you’re trying to overcome all the social inequity and oppression that occurs in this country.

The framework we have is for a “more perfect” union, and yet a perfect union it is not. And that has really set the tone within the Biden presidency as there is a commission to investigate the January 6 insurrection.

11 months in I really feel that there is a commitment to an idealistic vision to America, with Amanda Gorman’s inaugural poem "The Hill We Climb" really setting the tone for this journey. As I say in the book, America is only as good as how it treats its most marginalized people.

Along those lines, I’d like to talk a bit more about the Madres de Plaza de Mayo. That really stuck with me. In light of the ongoing separation of families at the border, what can we take from The Joshua Tree in the wireframe of liberation to continue this fight for freedom?

This is a heavy question. Madres de Plaza de Mayo was founded as a response to the forced disappearance of students, children, protestors and dissidents speaking out against totalitarian governments in Argentina who were aided and abetted by the U.S. government as part of Operation Condor.

The lesson in governmental transparency and not encroaching on inherent human freedoms should be central to American culture. Part of the idealistic vision of America discussed in the book is the mission inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, stating, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses,” and I firmly believe in this vision.

There have been times throughout our nation’s history where this standard has not been maintained, but when I see protests against family separations or even protests against racial and social injustice, it tells me that this spirit—both that the Madres de Plaza de Mayo as well as the spirit of an idealized America is still alive.

And to get to that place where we can be the best nation we can be for all people, it comes down to accountability. And it is our responsibility to maintain that accountability.

“Where The Streets Have No Name” has always seemed like one of those vague hope songs to me, and when I say vague I don’t mean that as a negative trait, but an invocation of the human spirit in the way, say, John Lennon’s “Imagine” dreams of no countries. With this mosaic of Ethiopian alleyways interwoven with rigid Irish class structure as the setting for this track, where do you think the idea of America and the American ideal fall into a roadmap of hope?

I like that connection with Lennon’s “Imagine.” Unlike a lot of rose-colored glasses songs that view these subjects of no borders or no divisions in humanity as a means of erasing systemic oppression, "Where The Streets Have No Name" doesn’t offer that same perspective.

There’s an absolutely deep recognition of the divisions we faced in 1987 and now. The Joshua Tree doesn’t posit America as something to be praised nor something to admonish, but reconciles the duality as a roadmap for where we are and where we need to be.

And you’re right, this track is rather vague because it came about at a time when Bono was really learning how to write songs. Before The Joshua Tree, he described his songwriting process as an act of sketching, essentially having the band find a sound and write the lyrics from there. And going back to what we were talking about in regard to accountability, “Where The Streets Have No Name” is really taking a look at where we are now, where we would like to be, and asking how we can get there.

Sonically, The Joshua Tree stands out from what a lot of folks would consider “the sound” of 1987. But in the grand metaphor of the desert, its outlier status allows it to persist in a way that, say, Appetite for Destruction feels very temporal. Can you talk a bit about what that moment in time was in terms of sound and how The Joshua Tree breaks this mold?

The Joshua Tree broke this mold by documenting the process of a group of Irhsmen reconciling their changing understanding of a nation that has had very deep cultural and spiritual impacts for them.

The Irish have been immigrating to the United States for decades, and my Irish people grow up thinking that this country is the promiseland, that this is the refuge.

Coupled by the fact that when the members of U2 were growing up, Ireland was one of the poorest countries in western Europe. The Edge has said, “The band only began to understand their own Irishness once [they] toured America.”

Seeing first-hand some of their beliefs or conceptualizations about America challenged was turned into art rather than a force of demoralization. And of course there are other albums that came out around this time that tried to speak to these issues—Sign O’ The Times by Prince comes to mind in its conversation around the experience of a Black man processing social inequality, economic inequality, and oppression.

And that album came from a deep, personal place for Prince. But as far as The Joshua Tree is concerned, both the creation of the album as well as the American desert itself was highly evocative for the band—it’s an entirely new landscape as there are no deserts in Ireland, there are biblical implications with regard to setting and pilgrimage, and it showed them that entire American experiences can be created (or remain inaccessible) simply due to the vastness in landscape. This juxtaposition between harshness and freedom inspired the band in so many ways.

This album is so global. In a way that juxtaposition between the starkness of the American desert and the richness of life, culture, desperation, and color outside of it, yet positing BOTH as types of beauty in conversation with each other, is a perspective that at the time I don’t think many mainstream American bands could have taken, whether that’s because of the state of American culture or just the type of music that was getting these major label contracts at the time. Do you think that Bono had recognized his unique position in offering this voice at that moment, or was it something mainstream audiences were starving for after a lot of fluff?

Well, the 1980s were Reagan’s America. It was a time of excess and individualism. Gordon Gecko’s famous line from the 1987 film Wall Street comes to mind, quote, “Greed is good.”

These myths of individualism and American exceptionalism are an extension of the founding framework of the U.S. We still struggle as a society to function as a collective, antithetically to how we operate as a species.

And I think Bono recognized this struggle early in their career, which separates U2 from many American bands who critique the States. Just this week was the 30th anniversary of U2’s album Achtung Baby, which includes the oft-misrepresented “One.” What’s interesting to me is that U2 has maintained this optimism about our responsibilities—it’s not that we have to rely on each other, it’s that we GET to. And this maturity in understanding what and who we are responsible for separates it from a lot of other pop and mainstream at the time.

I couldn’t do this interview without asking about Brian Eno, who at this point is regarded as an almost mythical figure. How did he get brought into the project? In your book you talk about his influence and development on Mothers of the Disappeared, but I feel like his influence is felt all throughout, especially in taking advantage of more reserved, quiet moments before that classic U2 soar.

Eno came on board to produce U2 for the album preceding The Joshua Tree in their discography, The Unforgettable Fire. Prior to this their sound was much more post-punk prior to that influence they took from Simple Minds’ New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84).

And Eno said no to working with them at first. They had to continually work at showing him new songs and new sounds aimed in the direction they wanted to take in order to secure his buy-in, and you can see how on The Joshua Tree this honed approach really paid off.

This new, soaring sound paired with a love for roots, soul and gospel music and Eno's sensibilities really give the album a new level of production capabilities—ending up with something as unique as the closing track, "Mothers of the Disappeared," which almost sounds like rain falling on a tin roof evocative of the poverty the Madres de Plaza de Mayo face each day in South America.

There’s an overwhelming sense of pervasiveness and an element of diabolical menace underscoring that track, and I think Eno’s presence really gave them the tools to do that.

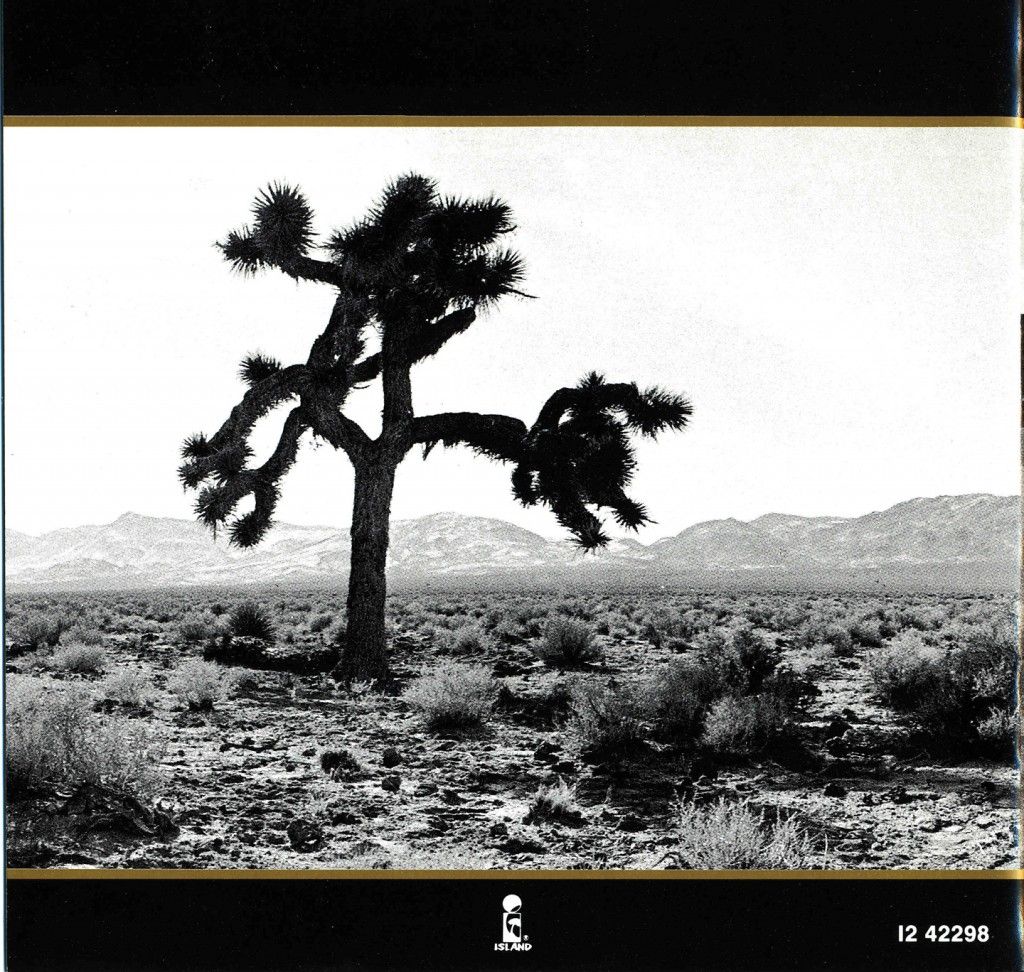

The back cover of the album features an image of a Joshua Tree standing alone in the desert. In your book, you write that this tree actually fell roughly 20 years ago, and has become a bit of a shrine to the band and this work. But this image of a fallen tree really sticks with me–the obvious metaphor being that the American empire is past its prime and yet continues to persist under less-than-ideal circumstances. But this can be taken two ways: One of refusing to get the message and recognize that it is no longer serving its mission, and one of hope, in that it knows exactly where it’s at and continues to serve as best as it can. Is this a hopeful image to you? Or an ignorant one? Or maybe a bit of both?

I wrestled with this idea as well. I visited in 2019, and let me tell you, it’s a considerable journey to reach that tree. It’s out in the middle of nowhere west of Death Valley

I wrestled with this idea as well. I visited in 2019, and let me tell you, it’s a considerable journey to reach that tree. It’s out in the middle of nowhere west of Death Valley

And by 2019, so much had happened in the Trump presidency that I had really done a ton of soul searching to look at my own identity, what it meant to me to be an American, and the responsibilities inherent to this.

And standing in the desert, looking at that fallen tree, it would have been easy to say that it’s a metaphor for a fallen empire. But also what I observed is that the tree also gave life to other trees around it, and it’s an important thing to consider when relating this image back to the United States.

For all of its flaws and all of its problems, there is a lot of good that comes out of the U.S. We HAVE gotten more democratic in so many ways, and the enduring spirit of our Civil Rights leaders, many of whom since have passed, inspire people to speak out each and every day.

These ideals didn’t die when Dr. King was assassinated, these ideals didn’t die when John Lewis was buried. The seeds are still sprouting. That’s the imagery I wanted to leave with.

Today is an interesting day to be doing this interview. Not only is it November 20, which makes it exactly 11 months since Biden’s inauguration, but it’s also less than 24 hours since the Kyle Rittenhouse acquittal. I appreciate you offering a moment of reassurance and a breath of context in a moment that feels inescapably heavy.

The Rittenhouse verdict is very disappointing and it is an indicator of where we are in this country and the work that needs to be done, and certainly you cannot ignore the fact that the privileges extended to him would not have been the same if he were Black.

I write in my book that Donald Trump emboldened white supremacy and legitimized this dangerous sense of nationalism. But apathy is a privilege afforded to those less likely to feel the impacts of inequality.

It’s an easy way to motivate folks with social power to do nothing. What keeps me motivated is knowing that the reward of fighting against these systems is so much greater than the temporary rest in just giving up.

And for me, as a white man, I have a very specific set of responsibilities inherent to my identity in this country. These setbacks just make it all the more apparent that there’s work that I need to be doing, that there are conversations I need to be having, to ensure outcomes like this trial do not continue to be the norm.

On "One Tree Hill," there exists a line about the “heart of darkness” and I thought this was such a clever way to talk about indigenous spaces. Bono was very inspired by the humanitarian work he was doing on the African content as well as personally inspired by a visit to New Zealand and making Maori friends. And yet there’s this element of British imperialism that weaves its way through all of these spaces—through Ireland, through Oceania, through Africa—and this track really brings the album together. In light of that, I’d love to hear your thoughts on Bono’s comments about always, “Disappearing into others’ lives,” through this lens of being a global citizen with a big old British boot on their back.

I think we need to take into consideration the time in which Bono grew up. This concept of disappearing into other people’s lives is just his way of recognizing how much larger the world is than he had grown up believing, that his understanding of it and his relationship to it is so much more vast and complicated than previously thought.

This goes back to what we were discussing earlier, in that The Edge had said, with the band only understanding their Irishness once they toured America. The vision of collectivism is only reinforced through making those global connections.

Now that we’ve spent two years in a global pandemic, what message do you think The Joshua Tree offers this moment?

The pandemic revealed in us this desperate need for a recognition of our interconnectedness that is so central to this book and this album.

We are more reliant on each other than we give credit for, and we are more reliant on others’ success than we previously believed. With what the pandemic has revealed in terms of social inequality, the loss of lives, and the inequality in access to healthcare, I mean what I say in that this country is only at its best when its most marginalized are taken care of.

In light of being granted Irish citizenship and completing the book, do you have any upcoming trips to Ireland planned? How do you think that writing the book and sitting in it not just through the Trump presidency but also through the pandemic will inform any upcoming travel or relocation you may have to Ireland?

Since he was elected I’ve said that I did not want to leave just because of Trump. But as a white man in America, I feel that my responsibilities here far outweigh the negatives for me right now. Once again, there is privilege in apathy, and I have no space for it.

Bradley’s book, U2’s The Joshua Tree: Planting Roots in Mythic America is available now from Rowman & Littlefield, Globe Pequot, and Backbeat Books.

Bradley’s book, U2’s The Joshua Tree: Planting Roots in Mythic America is available now from Rowman & Littlefield, Globe Pequot, and Backbeat Books.

Next entry: CIHRP Radio Weekly Voyages (Dec 6 - Dec 12)

Previous entry: CHIRP Radio Weekly Voyages (Nov 29 - Dec 5)