Now Playing

Current DJ: Jenny West: Music For Chameleons

Weaklung Banned Books from All Problems No Solutions (self-released) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

by Kyle Sanders

A peculiar thing happened to me while attending the press screening for We Grown Now, this year’s Opening Night title at the 59th Chicago International Film Festival: A family of six (including four children who could not have been any older than five years) walked in at around the half-hour point, clumsily staking out their spot.

After about ten minutes (of which half that time was spent settling into their seats), they got up and left. Apparently, they were not there to see Minhal Baig’s Chicago-set story about a friendship between two Black boys living in the Cabrini-Green housing complex during the early 1990s, but somehow didn’t realize their mistake until after quite some time. They exited the same way as they entered—as a thorn in my side.

While I found the disruption irritating (and before you judge me), I certainly didn’t blame the children. Despite the amount of time it took for them to settle down, as well as their inability to lower their voices, it’s the parents who should’ve recognized the faux paux sooner.

Because adults should know better, correct? This is something I was taught as a child: to listen to the adults in the room because “they know better.”

In We Grown Now (U.S.), little Malik and Eric are too young to know better outside the cinder-blocked walls of their Cabrini-Green homes. There, they each live with their non-nuclear families, gathered around dinner tables in the evenings while attending school during the day.

As much as their single parents work to provide for them, Malik’s mother Delores and Eric’s father Jason are unable to prevent the violence from crawling up to their doorstep. Once it does, the two boys must confront adulterated matters regarding racism, police brutality, and death.

We Grown Now

We Grown Now

Baig’s heartfelt story captures the gritty details of a community no longer in existence yet includes strokes of magical realism—those moments of make-believe all children use to add adventure to the mundane.

In one such instance, Malik looks past the water-stained ceiling of a condemned apartment and imagines a vast galaxy of stars leading elsewhere. But those moments become fewer and fewer as the reality of gang-related violence crowds into the boys’ reality, and even Eric begins spiraling into nihilist skepticism. We Grown Now is more than just a title—it’s a declarative developmental statement.

In A Happy Day (Norway), Hamid, Ismail, and Aras want nothing more than to escape the hopeless locale of a detention center. Without fences and guarded gates, this would be easy enough if it weren’t for the inescapable mountainous terrain that surrounds them. They yearn for something more and are willing to trek through the snowy conditions, until a new detainee causes one of them to fall in love and thwarts their plan.

A Happy Day

A Happy Day

What they’re running toward is just as much of a mystery as what they’re running from, as the detention center is never presented as sinister or abusive—just stuck in the middle of nowhere.

While every detainee is free to leave the premises once they turn eighteen, one of the three boys is a year younger, and suffers from hallucinations of a lone caribou. Is he the caribou, soon to be separated from his pack and left to survive on his own? And is the uncertainty of adulthood the same as what awaits then on the other side of that mountain? Both are mysteries to this trio of friends.

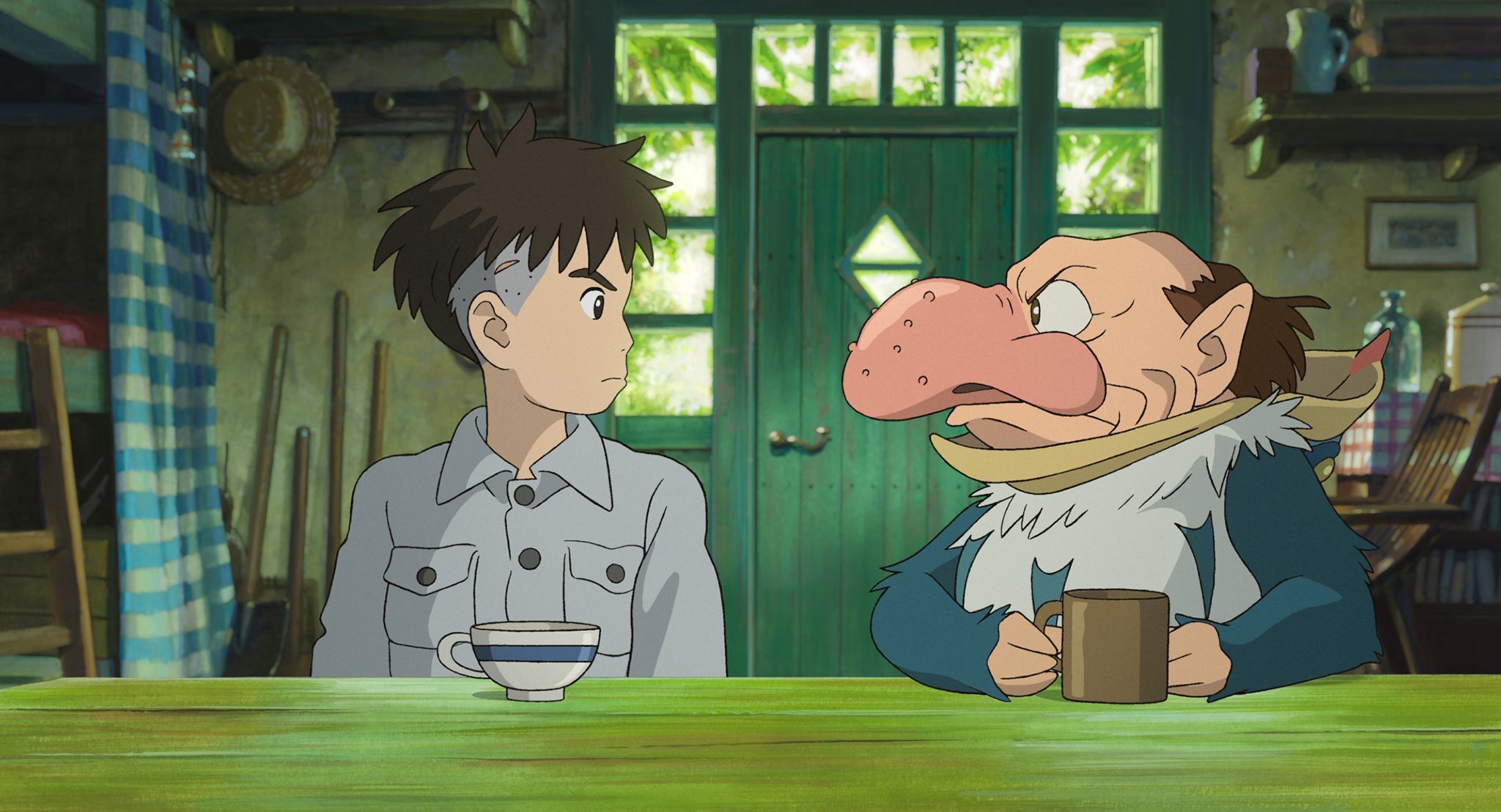

In Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (Japan), young Mahito is less curious about the other side of a mountain than he is about a mysterious tower located on his future stepmother’s country estate.

Warned by his stepmother’s seven elderly maids (a nod to Snow White, perhaps?) that the tower was built under mysterious circumstances by his great-uncle, it is within this tower that Mahito must face uncertainty to rescue his stepmother from its perimeters.

With the help of a mischievous grey heron—who happens to be a small man inhabiting the bird’s body—Mahito enters a strange and magical world of malevolent birds and countless realms in which he must search for his stepmother.

The Boy and the Herson

The Boy and the Herson

Produced by Studio Ghibli, The Boy and the Heron could almost be mistaken as a Disney flick, as it borrows from that franchise’s formula. Mahito’s mother is tragically killed in the beginning, and his father, Shoichi, is primarily absent and preoccupied with work.

It doesn’t help that Shoichi relocated Mahito from his childhood home to the countryside where his future stepmother lives—who happens to be pregnant with Shoichi’s child. Yet Mahito overcomes his circumstances, and through his journey, learns that in order for a world to maintain balance, it must be without malice.

The adults of Monster (Japan) are entirely too comfortable with malice. In this film, there are three different versions of the truth behind young Minato’s strange behavior. The first point-of-view is from his mother, who notices her son acting strangely. She suspects Minato is being bullied, and he reluctantly confides that the culprit is his teacher, Mr. Hari.

From there, we are provided Mr. Hari’s viewpoint, which ultimately reveals something else entirely regarding how the school system handles accusations of abuse from teachers. Finally, we are provided Minato’s side of the story, which involves a far more delicate scenario that includes one of his classmates, an eccentric and misunderstood boy named Hoshikowa.

Monster

Monster

It is this friendship between Minato and Hoshikowa that is explored in the film’s third act. While the adults are busy handling school politics and public images, there’s a connection being made between two boys who share an intimacy that none of their classmates or even the grown-ups understand.

At first, this relationship causes confusion in Minato, as he struggles with relating to someone whom his classmates view as “different.” It also doesn’t help that Minato’s mother holds expectations for Minato’s future that his feelings toward Hoshikowa threaten to dissolve.

To live happily or to suffer quietly is a decision too mature for Minato to handle, but he knows it is a choice only he can make for himself.

Societal pressure also affects teenaged Abel in Explanation for Everything (Hungary). Before he can graduate high school, the fate of his future depends on the passing of an oral history exam that he’s been studying for. Needless to say, the exam doesn’t go so well, and when his strict father demands to know what Abel’s excuse is, the “explanation” causes a chain reaction of events that blows up into a national scandal.

Explanation for Everything

Explanation for Everything

Once again, the adults take on the issue themselves, causing more problems for everyone than is necessary. Abel’s father wants to ensure his son has a future filled with opportunity, while Abel’s teacher believes Abel’s failure was of his own making and must deal with the consequences.

A confrontation ensues, and liberal views are pitted against nationalist pride (sound familiar?). As the adults resort to childish arguments, it is Abel who finally does the “grown-up thing” and admits what really happened. While it’s easy to direct blame on something else, the more difficult task is to admit to your wrongdoing and grow from your failures.

Essentially all of these young characters face scenarios that require a little growing up on their part. The adults responsible for them, who do their best to support and protect, only seem to make matters worse by interfering. It is ultimately the child who holds their fate in their hands.

Growing up can take place at any age, it just requires a decision, regardless of what happens next. It might be the wrong choice, but hopefully they'll “know better” the next time. I hope those kids who interrupted my viewing of We Grown Now learned a valuable lesson from their experience: pay attention to the theater number on the ticket stub!

Previous entry: CHIRP Radio Weekly Voyages (Oct 16 - Oct 22)