Now Playing

Current DJ: Joanna Bz

Rufus Maybe Your Baby from Rufus (ABC) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

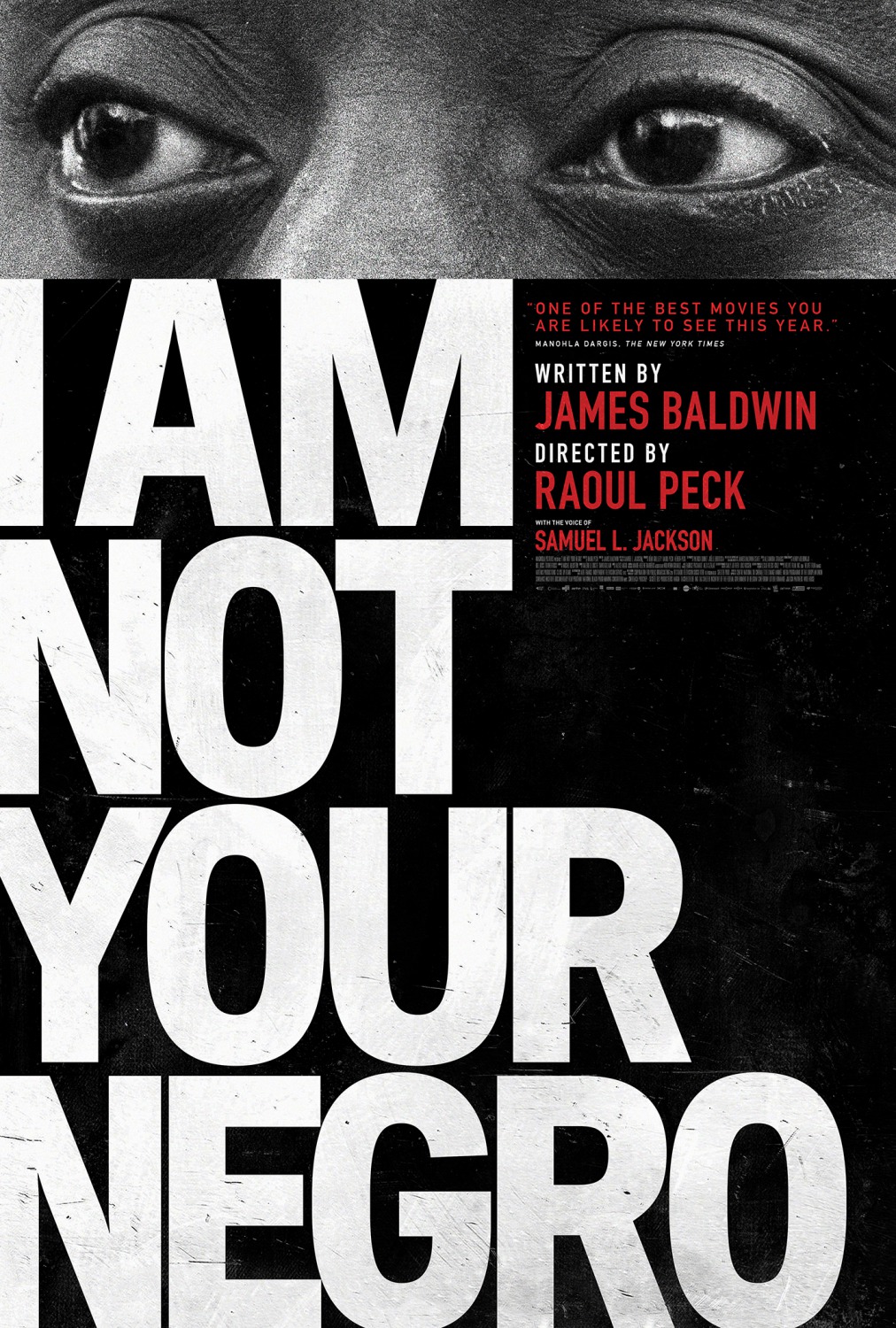

[Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's weekly e-conversation on cinema. This week, the discussion is about the James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro. This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.]

Kevin: Clarence, while digesting the myriad of themes in I Am Not Your Negro, I got the feeling that director Raoul Peck had enough material here for three documentaries, not just one? The film pinballs between the life of writer James Baldwin (whose unfinished manuscript Remember This House formed the backbone of the movie) and his recollections of assassinated civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. In addition, we're also treated to a powerful, disturbing visual collage ranging from Hollywood films to newsreel protest footage -- one which shows us just exactly what white Americans thought of their black countrymen during the early/mid-20th century.

Kevin: Clarence, while digesting the myriad of themes in I Am Not Your Negro, I got the feeling that director Raoul Peck had enough material here for three documentaries, not just one? The film pinballs between the life of writer James Baldwin (whose unfinished manuscript Remember This House formed the backbone of the movie) and his recollections of assassinated civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. In addition, we're also treated to a powerful, disturbing visual collage ranging from Hollywood films to newsreel protest footage -- one which shows us just exactly what white Americans thought of their black countrymen during the early/mid-20th century.

It's that collage which stuck with me the most. How far have we come as far as racial reconciliation? Peck's juxtaposition of police-brutality videos of yesteryear with today's social unrest seems to suggest that we haven't traveled very far at all. While whites no longer line up with signs (and worse) to oppose the integration of schools and communities like they did in decades past, are we not still a largely segregated society, albeit informally?

But I also found myself wondering what Baldwin might think of today's imagery, from hip-hop to Hollywood. And of course... what would he think of the Obama presidency? In 1963, there was a famous meeting on race relations between then-attorney general Robert Kennedy and a number of cultural leaders assembled by Baldwin. In an interview recounted in the film, Baldwin wryly observed a Kennedy comment during the meeting that America could have a black president in 40 years -- a claim which Baldwin viewed as preposterous given the centuries it had taken his family to merely escape poverty. And yet... the very next scene cuts to Obama's inauguration. It's a tantalizing but fleeting moment, as Peck wordlessly slingshots us back to Baldwin's era shortly thereafter.

In a clever touch, Baldwin's own words (voiced by Samuel L. Jackson) are the only narration used by Peck in the documentary; Baldwin is even posthumously given a writing credit on the film. And via Baldwin's prose and interviews, Peck constructs a portrait of a noble, eloquent man who is proud, yet sardonic about the place of his community within American society. I found myself wishing for the sorts of things you typically expect to find in historical documentaries -- namely, thoughts on Baldwin from both his contemporaries as well as today's scholars. But that would have made for an entirely different film, and the message here belonged to Baldwin alone.

Let me backtrack to that Kennedy/Baldwin meeting involving "cultural leaders." Is the whole notion of a demographic group having cultural (or political) leaders antiquated in today's day and age? I suspect that some might think of Ta-Nehisi Coates as perhaps a successor to Baldwin; do you know of other writers who reflect the range of experiences within modern black America?

Also, what are your own thoughts as to current visual imagery and race? During the documentary, there was footage and mentions of minstrel performers such as Mantan Moreland -- sadly, the "non-threatening servant" was the only minority archetype that didn't ruffle the feathers of white America. Spike Lee has argued in recent years that some of the damage is now self-inflicted, via Tyler Perry and the like. (Chuck D of Public Enemy makes a similar case re: hip-hop.)

I mentioned earlier that the specter of segregation seems to largely still be with us today. Chicago is a famous example of this, and it's hard not to notice the fact that, at most of the cultural events I attend here (concerts, independent films, etc.), the audiences are almost always overwhelmingly white. I don't mean to insinuate here that the problem revolves around other folks who aren't attending my events -- it's a two-way street, and I'm as much to blame. How much of this is the culture, and how much is geography?

Clarence: When I think about these questions you pose, Kevin, I think about the deserved refutation of Francis Fukuyama's thesis about history. In today's society we're often encouraged to look at these issues as if we're standing on the outside looking at some separate culture that we've moved beyond. But history is never done with us, and the problems Baldwin stared straight in the face are still with us, albeit in different degrees and forms.

To me, I am Not Your Negro stands with OJ: Made In America as required viewing for anyone who is interested in the history of race and racism in 20th century America. Of course, neither film gives the whole story, but the particular points of view of these two talented and accomplished yet very different figures shows how there are as many different stories within the black community as there are between the different races and ethnic groups.

So I don't think a single person like Coates (a fantastic writer) can represent the total, or even the general, experience of being black in America. What he can do, though, is tell his story for others to read, hear, and learn from.

I'm not a person who believes "nothing's changed" as far as racial attitudes in America, but I do believe racism is still a fundamental part of American culture, language, and custom. There's always been somebody to hate in this country for one reason or another. This weekend in Chicago, a group of protesters is holding an "anti-Sharia" march downtown to protest the Muslim holy book (there are already several counter-protests planned as well). The group is using the same tactics as the odious Westboro Baptist Church in using the public space to loudly proclaim who they hate.

A hundred years ago, these people would have been wearing sheets and enjoying the open support of public officials. These days, approving these actions could cost someone their job or reputation. So the feelings are more reserved...but they are there.

As far as imagery in African-American entertainment, one area I'm seeing a definite shift is in music. The current group of young black artists we play on CHIRP Radio (Kendrick Lamar, Chance the Rapper, JLin, Serengeti, Azealia Banks, MadLib, and on and on) has shown little interest in emulating the "Thug-ness" or "Bling-ness" of the generation before them. I think this is a very healthy sign of creative evolution.

On the other end, I'm not a Tyler Perry fan in the least. His act is so backward, so insulting to black people, it makes me angry to just think about it. Not to mention the basic quality of the work. The acting, writing and directing in all of the Perry projects I've seen have been terrible.

But other black people love him and his movies because he's successful and especially because of his underlying messages about family and traditional values. This brings things back to Baldwin, because there's another part of his identity that's critical to how he is perceived by his racial group - Baldwin was openly gay. That fact got him dis-invited from speaking at the 1963 March on Washington and (I'm convinced) pushed to the margins of thought leadership by groups like the NAACP, an organization he criticizes in the documentary . A significant portion of the black community (especially the black church) still has a problem with homosexuality, for whatever reason. Hate is not just the domain of angry white people.

Barrack Obama was wrong. There very much are Red States and Blue States in America, and there are Red and Blue areas within those states, physically and mentally. The America that Baldwin had to deal with is still here. I look at the 2016 Presidential election map and see the blue dot of Chicago surrounded by a sea of red, and I think of how large cities are not places for the intolerant. Even if the events you frequent tend toward homogeneity, I have trouble believing that most Chicagoans live here because they want to be surrounded by their own kind. The suburbs and the country is a different story.

Kevin, has any film you've seen (fictional or documentary) changed your perception of a particular group of people? And do you think in general it's the artist's (or anyone's) responsibility to change minds about a demographic?

Kevin: At some point, Clarence, we should discuss OJ: Made in America in detail -- I agree with you that it was another tremendous reflection on race and culture. In fact, I preferred it to I Am Not Your Negro, but: A) it had 467 minutes to work with, as opposed to the latter's 93; and, B) I still appreciated IANYN's unique style immensely.

As far as the Westboro Baptists and the anti-Sharia marchers... well, the existence of these folks is depressing, but free speech is free speech. Let's hope all sides remain non-violent, unlike the hooligans in Portland. I've actually thought a great deal about parallels between black and Islamic communities in America -- both have been on my radar for quite a while. One of my oldest and closest friends is Muslim, and we both attended the same majority-black school district in Willingboro, NJ.

[Willingboro was built in the 1950s by Abraham Levitt, who had a policy of not selling to black families. This was successfully challenged in court by an Army officer named W. R. James, and by the 1970s, homeowners were told that "their neighborhood was becoming increasingly African-American and home values could decline if they did not sell quickly." Cue white flight. Where formal segregation ends, voluntary segregation begins?]

As shown in IANYN, the visual imagery of black America throughout much of the 20th century often portrayed the community as shiftless, servile, and dumb. And the images of Muslims (who, to many, are synonymous with Arabs even though most Muslims aren't Middle-Eastern) certainly hasn't been positive either. Is it better to be labeled as dangerous as opposed to incompetent? Not exactly an enviable choice. There's a great documentary called Reel Bad Arabs (available here for free) which discusses the breadth of these stereotypes via the research and narration of Dr. Jack Shaheen.

Assimilation, however, is the key here, right? It certainly could be viewed as presumptuous to suggest that other communities surrender a portion of their culture to the American way of life, but the fewer barriers we have, the more we accept one another. We've seen it with other immigrant groups -- whether it's Asian parents who give their kids Anglo names, or interfaith marriages between Christians and Jews. It's been commented that the insular nature of Islamic communities in Europe has been a big source of friction. Is that also the case here? The good news is that things are changing -- we're seeing more Muslims in popular culture, for instance, such as Aziz Ansari of Master of None.

You make a very interesting point about how Baldwin was partially ostracized by the civil-rights community because of his sexuality. What I've always found fascinating is that U.S. House Representatives from black districts generally have the most liberal voting records in Congress -- even though their constituents often possess (due to the impact of the church, as you mentioned) quite conservative views regarding issues like gay marriage and abortion.

I don't know that it's any artist's "responsibility" to change minds -- to thine own self be true as far as storytelling. I will say, though, that I'm much more receptive to messages which don't come via heavy-handed moralization. Have I seen any films which have impacted my view of a population? Here are a few which come to mind:

* The documentary Devil's Playground certainly made me feel less sympathy for the Amish, seeing as how they offer their youth the illusion of freedom via the rumspringa -- but in essence, these kids have been set up to fail and thus ultimately return to their communities.

* Wadjda, the first film directed by a Saudi Arabian woman in Saudi Arabia, brought the plight of women in conservative Islamic countries home. This sort of thing generates a great deal of cognitive dissonance for me; while the anti-Sharia marchers are generally intolerant bigots to be shunned, much of the culture in these religious communities still seems rather repressive.

* Did you ever watch a film called White Man's Burden, with Harry Belafonte and John Travolta? I wouldn't say it was a great film, but it sure was an intriguing one, featuring an alternate universe where the races were flipped as far as social standing in America. One of the first scenes involves Travolta trying to buy a doll for his daughter. Guess what? All the ones in the store are black. I don't know that it "changed my perception of a people," but it was an interesting experiment as far as walking in someone else's shoes.

* And on a similar note, there's CSA: Confederate States of America, a brilliant faux-documentary about the history of America in an alternate timeline where the South had won the Civil War. There are repeated interludes during the film to air racist "commercials" that seem incredibly over-the-top... until you find out at the end of the film that the products they advertised were real. Ouch.

How about yourself? And, we both grew up with The Cosby Show, I'm guessing? Let's leave Bill Cosby's disturbing history with women aside for the moment. Black and white TV audiences have long been segregated re: viewing habits, but The Cosby Show was the #1 show in America for five straight years in the 1980s. While the show received praise for portraying an upper-middle class black family headed by successful professionals, others believed that it helped desensitize white America to the problems of racism. Your thoughts?

Clarence: There was a book written about The Cosby Show by Sut Jhally and Justin Lewis called Enlightened Racism that has some surprising findings about audience reaction to the show. The authors discovered that, rather than reducing racist views or desensitizing viewers to the issue, the show actually encouraged racist beliefs in some viewers who kept comparing real-life black people to the picture-perfect and completely fictional Huxtable family. Dad's a doctor, mom's a lawyer, kids are adorable, every relative is a jazz musician, and so on. "Why can't those blacks in prison and on welfare be more like Dr. and Mrs. Huxtable?" these viewers asked themselves while concluding it's because they can't (lack of intelligence) or they won't (lack of discipline or will power).

In this context, The Cosby Show could be seen as one example of the double-edged sword of assimilation - on the one hand, we all have to agree to live by a certain set of social and legal norms. But how much of that means giving up one's cultural identity in terms of dress, food, language, or whatever else makes you you in order to fit in with the dominant group? What if you fail to clear the social and economic barriers the dominant group has put in your way? Does that say something about you or them?

And since a group's perception of itself is rarely the reality, is becoming a "typical" American (whose main features seem to be consumerism, anxiety, unhealthy living, and hostility toward and ignorance about the rest of the world) really a goal worth perusing anyway?

The Cosby Show is also example of how much power is inherent in the stories we tell ourselves, no matter what format or genre they are in. When it comes to the power to change perception of social groups, one film that did it for me was Lionel Rogosin's fiction-doc On the Bowery. Until I'd seen that movie, I didn't really think much at all about poor people. But this movie really brings home the desperate plight of people at the bottom rung of the social ladder. That movie as well as Billy Wilder's film The Lost Weekend also made an impact on me in terms of portrayals of alcoholics, who in American films and TV shows are often shown in comic situations.

Unfortunately, I don't think the groups of people who would benefit the most from seeing IANYN, white and black, are going to watch it, But that's par for the course for this kind of film. I'm glad that this film exists as part of the "conversation about race," that seems to often to be driven by internet arguments and sensationalist news stories that are as much about entertainment as exploring America's social issues.

One of Baldwin's talents throughout his life was his ability to speak plainly and forcefully about and to people in power. While I admire his bravery in taking these stances, I've been enlightened by his refusal to make racism a problem that he's responsible for solving. My favorite quote from IANYN, and maybe my favorite quote regarding the issue of race in the 21st century, sums up how I feel about the situation after getting to know this great man:

"What white people have to do is try to find out in their hearts why it was necessary for them to have a n*gger in the first place. Because I am not a n*gger. I'm a man...but if you think I'm a n*gger, it means YOU need it...and if you invented him, you the white people invented him, then you have to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that."

Did you see the movie? Want to add to the conversation? Leave a comment below!

Next entry: Two Americas: Reflections on Life and The Joshua Tree at 30

Previous entry: CHIRP Radio’s First Time Series Is Coming to Printers Row Lit Fest This Saturday